The $3 million lawsuit filed against Boston College advanced another step toward trial this past week, as the plaintiff’s lawyer filed briefs on Friday to the Massachusetts District Court arguing that the scope of the civil suit should be wide-ranging. The University’s legal response is due this upcoming week.

In the time since BC processed this disciplinary matter, the University has overhauled its entire disciplinary process pertaining to sexual assault. In addition, it should be noted that when the alleged incident originally occurred, the plaintiff, identified only as “John Doe” in court documents, was reporting on an event for The Heights.

“All agree that the First Circuit narrowed the legal and factual scope of this case on remand to some extent,” the brief said. “But the claims before the Court on remand, and which a jury will be tasked with deciding, do not fundamentally change what this case is about: whether the University breached its obligations to John, and whether those breaches caused John to be wrongfully convicted and to suffer emotional, reputational, and financial harm that will endure long beyond his time at the University.

“The University’s characterization of the factual scope of the remanded claims, however, is predictably and improperly narrow.”

This will be the first jury trial of a due process suit filed after the Obama administration reinterpreted Title IX doctrine in 2011, according to Brooklyn College professor K.C. Johnson, who chronicles Title IX litigation.

The plaintiff filed the lawsuit after the University would not reverse a disciplinary decision that went against him over an alleged sexual assault that took place on the AHANA+ Leadership Council Boat Cruise in 2012.

The investigation into the incident led to Doe being charged by the University for assault rather than sexual assault and a three-semester suspension. Shortly after his suspension was issued, the criminal charges pending against him were dropped after exculpatory video evidence was found by the police. Doe’s two appeals of his University suspension fell on deaf ears, leading to his lawsuit against BC.

BC has argued that the alleged breach-of-contract violation should only be subject to a review of whether former Dean of Students Paul Chebator’s and former Executive Director for Planning and Staff Development Carole Hughes’s interactions with the hearing board that handled Doe’s case were improper.

The briefs filed by the plaintiff’s side last week argue more specifically in regard to how evidence in the case will be handled. The University is arguing that the scope of the trial take into account only two pieces of evidence, both pertaining to allegedly improper communication between Hughes and Chebator. The plaintiff’s side said that far more should be taken into account in order to make the case comprehensible to the jury, according to the brief.

The plaintiff’s side cites the appeals court decision that remanded the case back to district court as noting the importance of Doe’s original argument for his innocence: Doe said in his testimony that a student only identified as “J.K.” in court documents actually perpetrated the assault. The plaintiff’s side is arguing that “Hughes’ refusal to even consider that J.K. might have committed the assault effectively deprived John of [a] defense.”

The BC Student Handbook guarantees the protection of fair student rights during BC disciplinary processes, which the plaintiff’s side argues means that the University did not provide Doe with a fair procedure.

In addition, the plaintiff’s side is asking to present evidence to the jury pertaining to information Hughes and others were privy to in the wake of the allegations emerging. The argument given in the brief is that before Hughes communicated with Chebator, she “mishandled” the situation. The brief cites six examples of events that took place prior to Hughes’ communications with Chebator that the plaintiff’s lawyers said they believe need to be considered by the jury.

The plaintiff’s side is also citing Doe v. Amherst College, 2017 in its argument, where a plaintiff also going by “John Doe” in court documents won a lawsuit against Amherst for wrongly expelling him without fairly evaluating his defense.

The parallel to the BC case is that BC’s John Doe is trying to prove he made an “exculpatory and complete defense,” as the brief puts it—which would potentially provide a precedent for the judge and jury to follow.

The plaintiff went on to describe why BC is defending itself by trying to limit the scope of the trial: If this case has to do with procedural errors rather than a more conscious effort to prevent Doe from exercising his rights at his hearing, that would mean the University was acting “in good faith.” In such a scenario, that would mean that Doe was properly charged and properly found guilty—“[defeating] the purpose of the trial on the claims remanded by the First Circuit [Appeals Court].”

Doe is also requesting to submit evidence based on “basic fairness,” an argument that hinges on “source of duty” and “the standard of basic fairness in the context of higher education discipline,” according to the brief. The basic fairness claim covers the same issues as the breach-of-contract claim does, but rather than appealing to the fairness promised in the BC student handbook, it appeals to an “implied covenant of good faith and fair dealings imposed on every contract in Massachusetts law,” as the Appeals Court decision vacating the prior District Court decision put it.

The plaintiff’s side is bringing Brett Sokolow, a lawyer who founded the largest education-specific law practice in the country and typically works for and represents colleges and universities, in as an expert witness. Sokolow submitted testimony as a part of the briefs filed by the plaintiff, arguing that Chebator; Joseph Herlihy, BC’s general counsel; and Nora Field, BC’s deputy general counsel all served “improper” roles in Doe’s disciplinary process.

Sokolow argued that Chebator steered the outcome of the hearing, despite operating as “the sole appellate officer,” and that Herlihy and Field executed the role the Title IX coordinator should have served. The Office of Civil Rights, according to Sokolow, explicitly stated that this may not occur due to potential conflict of interest issues.

“The conflict of interests arises because the interests of the University and the interests of the individuals operating the impartial process required by Title IX are no co-extensive,” Sokolow said.

He also argued that Hughes mishandled the case on multiple occasions outside of and before communicating with Chebator. In addition, Sokolow argues that the University failed to adhere to multiple aspects of Title IX requirements, including a failure to investigate, provide fair and meaningful notice of the charges, provide an appropriate and fair hearing date, provide adequate training for hearing board members, provide an unbiased hearing board, and document the hearing proceedings.

Sokolow also echoed the plaintiff’s previous arguments concerning mishandling of witnesses, failure of proof, manipulation of evidence, failure to adhere to the presumption of innocence, and gender bias issues. The appeals court did not remand any gender bias claims back to the District Court, but such complaints are featured in Sokolow’s arguments, as he said that gender bias affects the entire outcome of the case.

Sokolow also submits arguments pertaining to former Vice President of Student Affairs Barb Jones’ involvement in the 2014 review of the disciplinary proceedings, which was begun at the behest of University President Rev. William P. Leahy, S.J., granting the request of Doe’s parents to give the situation another look. Jones found no issues with the disciplinary proceedings in her investigation, which Sokolow disagrees with, referencing his previous arguments for how various BC administrators acted improperly over the course of the disciplinary proceedings.

He also added further criticism of Herlihy’s continued involvement, this time in the review, despite an “additional, personal interest” from being involved in the previous outcome.

The briefs also include expert testimony explaining how much money Doe would theoretically be owed if the court finds that the damages Doe is asking for are appropriate. Doe is asking for both $3 million and expungement of his disciplinary record due to emotional distress, expenses incurred during his three-semester-long suspension, lost earnings as a result of his delayed graduation, diminished earning potential, and reputation cost.

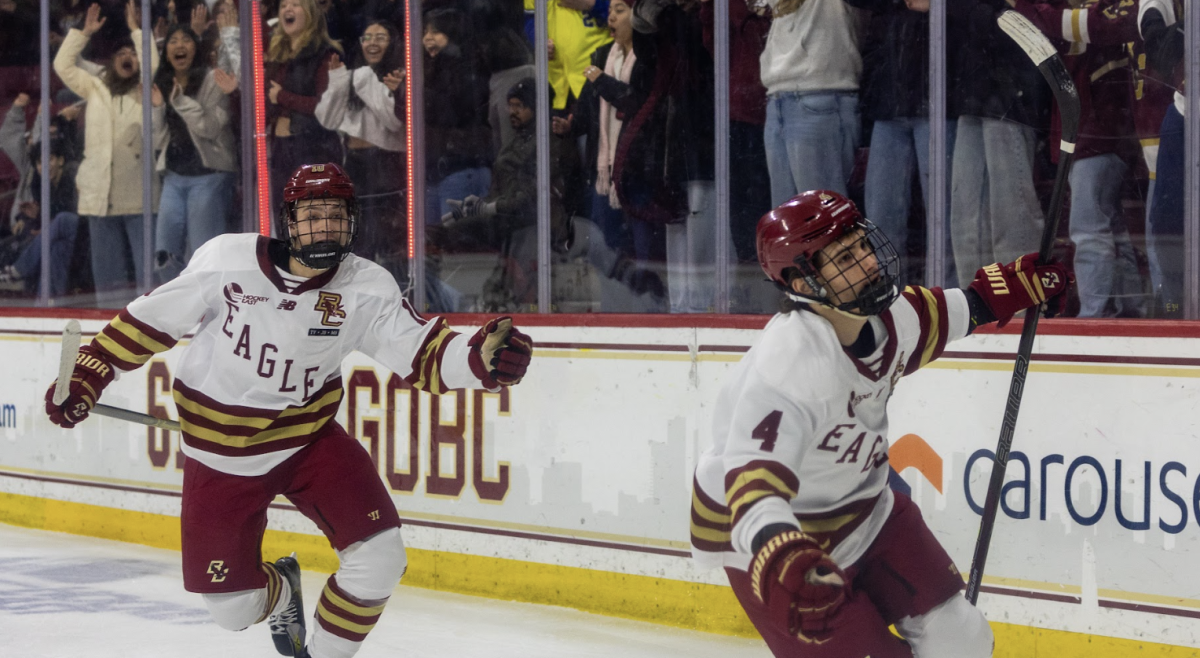

Featured Image by Celine Lim / Heights Editor