Ahead of a hearing scheduled to take place this coming Thursday, Boston College, in the $3 million lawsuit brought by a alumnus—identified only as “John Doe” in court documents—submitted its brief in support of limiting the scope of the upcoming jury trial as much as possible this past Monday.

The brief provides a rebuttal to many of the requests put forward by Doe on Feb. 15.

“Doe’s scope-of-trial memorandum misstates the First [Circuit Court of Appeals’] decision and ignores the ruling [the District Court] already has made in light of that decision about the issues remaining to be tried,” the University’s brief says.

“The [District] Court’s ruling was firmly grounded in the clear language of the First Circuit’s decision, which affirmed summary judgement for BC on all claims except breach of contact and basic fairness specifically in relation to … two allegations of alleged ‘interference’ with the Hearing Board’s decision.”

The plaintiff filed the lawsuit after the University did not reverse a disciplinary decision that ruled against him over an alleged sexual assault that took place on the AHANA+ Leadership Council Boat Cruise in 2012. When the alleged incident originally occurred, the plaintiff was reporting on an event for The Heights.

The Massachusetts District Court is considering breach-of-contract and basic fairness claims that Doe is claiming in his lawsuit. A jury trial is scheduled to take place in April, the first of its kind since the “Dear Colleague” letter the Obama administration administered in 2011 redefined Title IX guidelines, according to Brooklyn College professor K.C. Johnson, who chronicles Title IX litigation. This case is also now the oldest accused student lawsuit remaining in the court system after the lawsuit against Miami University (Ohio) was settled last week, according to Johnson.

The plaintiff’s representatives argued in briefs filed two weeks ago that evidence pertaining to alleged mishandling “long before” former Dean of Students Paul Chebator’s and former Executive Director for Planning and Staff Development Carole Hughes engaged in improper interactions with the hearing board that handled Doe’s case should still be considered by the jury.

BC is arguing that Judge Denise Casper ruled at a prior hearing that only Chebator and Hughes’ communication with the hearing board would be considered—specifically the “scope of the evidence that will be offered (or contested) at trial, not about the scope of the issues to be tried,” according to the brief.

The University is arguing that, despite the fact that “Doe can testify about evidence that was presented at the [disciplinary] hearing, including the evidence he presented in support of his ‘alternative culprit’ defense,” that does not mean expert witnesses should be able to do so, nor does it mean that the new trial should focus on whether or not Doe committed the assault.

During his disciplinary hearings as a student, Doe’s defense against the charge hinged on his argument alleging that a a third party—identified as “J.K.” in court documents—committed the assault.

The University is arguing that the “forensically enhanced” video that was considered exculpatory evidence by the criminal prosecutors that dropped charges against Doe for sexual assault should not be presented in court, since it was not available to the hearing board members. Since this trial is not supposed to reconsider whether Doe committed assault, but whether BC breached its contract with Doe, presenting additional evidence is not necessary, according to the brief.

Doe’s lawyers have argued that the video should be considered by the jury because the hearing board declined to wait to see the enhanced video, and the video there was not considered exculpatory when BC considered Doe’s appeal of the original decision with the enhanced video. BC’s response has been that charges relating to the appeal and 2014 independent review have already been ruled in the University’s favor, rendering the context irrelevant.

The University is particularly concerned with the idea that further witnesses will be called. Doe’s legal team is seeking testimony from Brett Sokolow—a lawyer who founded the largest education-specific law practice in the country and typically works for and represents colleges and universities—to be heard by the jury. Sokolow makes arguments related to Title IX guidelines BC allegedly violated, but the University is arguing that since such matters were ruled on by Casper’s summary judgement when this case first went through District Court in 2016, Sokolow’s testimony shouldn’t be considered.

Doe originally brought six claims against BC, four of which Casper and the Appeals Court ruled in favor of BC via summary judgement. Those included Title IX gender-bias related claims, negligence, and negligent infliction of emotional distress. Only the breach-of-contract and basic fairness claims need to be decided during the jury trial, but according to Sokolow’s testimony, improper execution of Title IX guidelines and gender bias are tied to the breach-of-contract and basic fairness claims.

To Sokolow, the case was mishandled because of a lack of adherence to Title IX guidelines. To the University, that issue has already been ruled on, rendering his argument unrelated to the matters yet to be tried. In addition, the briefs state that between Doe and members of the University hearing board, explanations for how the charges were brought, how the hearing was conducted, and any other details related to Doe’s hearing will be covered. If that is the case, as BC argues, there is no need for any witnesses to be brought.

The University is also arguing that expert witness testimony will “usurp” the authority of the jury, further rendering Sokolow’s testimony irrelevant. The brief also criticizes Sokolow’s argument that BC “failed to follow the ‘custom and practice of the field.’”

“Whether BC followed the ‘custom and practice of the field,’ assuming one exists, is irrelevant,” the brief says. “What other universities do, and how they do it, is irrelevant to whether BC met its ‘express contractual promises’ to Doe.”

The University also says the plaintiff’s arguments for witness testimony would only be valid if negligence was the charge, in addition to explaining that breach-of-contract cases are far different and do not typically involve expert witnesses.

BC’s representatives argued that Sokolow’s testimony inaccurately defines the BC student handbook guidelines and what is required by law before noting that an expert is able to do neither.

“What basic fairness in the context of this case is something the First Circuit already has specified: It would be a breach of contract and violation of basic fairness if the Deans interfered with the Board’s deliberations,” the brief says. “What remains to be determined is whether, as a matter of fact, that happened.”

BC also argued that two other liability experts that Doe’s side is planning to call to the stand at trial should not be allowed to testify. The University said one of the experts’—the videographer responsible for analyzing the video that Doe’s side believes is exculpatory Michael R. Garneau—testimony would be irrelevant since it would be based around Doe’s innocence, not whether the University broke its contract with Doe.

BC is arguing that the other witness, Nancy Moore—an expert on professional ethics for attorneys and a Boston University law professor—will also present testimony that is irrelevant to the trial. BC is positing that since she intends to testify about allegedly improper activity by BC’s general counsel and deputy general counsel, Joseph Herlihy and Nora Field, respectively, it is unnecessary for Moore to have her testimony heard by the jury. Part of the University’s justification for making this request is Casper’s earlier ruling that Herlihy and Field should not added as defendants in the lawsuit and ruled that Herlihy “did not interfere with the Board’s deliberations.”

This argument will conflict directly with Sokolow’s testimony when Casper considers the issue next week. Sokolow explained in the plaintiff’s briefs that, in his opinion, Herlihy and Field’s actions directly contributed to why BC broke its contract with Doe. He believes that both both Herlihy and Field operated in roles that the University’s Title IX coordinator should have filled to afford Doe a fair disciplinary hearing.

BC’s final argument has to do with exactly what types of damages the jury can consider for Doe if the jury rules in his favor. The University’s side is arguing that damages related to the breach-of-contract can be considered—educational costs and lost income racked up due to his graduation both from BC and law school being delayed.

The University is also arguing that any damages relating to emotional distress or reputational harm cannot be considered.

The brief states that physical harm, intentional or reckless conduct, or an inherent aspect of the contract that could inflict emotional harm is required to prove that emotional distress damages can be considered. The University argued that it is guilty of none of those things. BC cited Casper’s previous decision as confirmation that Doe has not presented any evidence showing the University’s engagement in outrageous conduct. On the contract issue, BC said that nothing within the student handbook “would make emotional distress a foreseeable result of a breach.”

The University is also arguing that reputational damages from an improper issuance of a criminal complaint are not the same as theoretical damages incurred by the improper issuance of a university disciplinary decision.

BC said that because of these arguments, Doe’s psychiatrist, Michael Bain, and vocational expert, Stephen Shedlin—who has submitted testimony detailing exactly how much money Doe is owed—should not be allowed to testify at the trial. BC is taking particular issue with the methodology, or in the opinion of the University, the lack thereof, behind Shedlin’s calculations, labeling Shedlin’s testimony “inadmissible”.

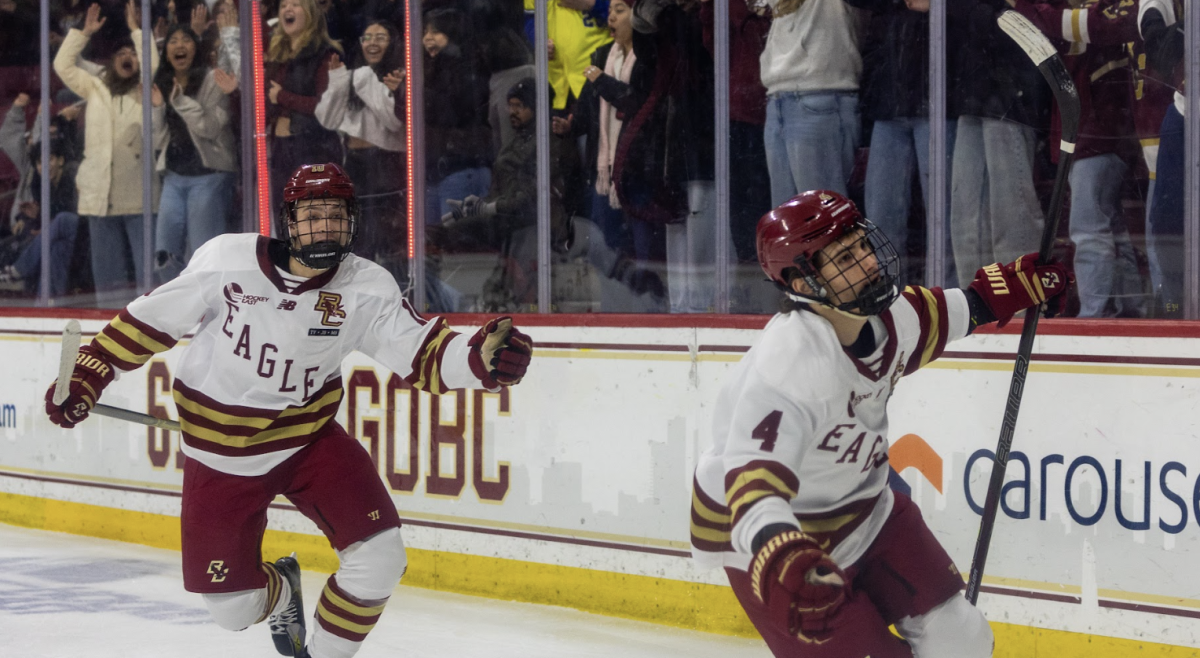

Featured Image by Celine Lim / Heights Editor