A recent lawsuit alleging that Boston College violated a student’s fair process rights could force colleges and universities across New England to reevaluate how they investigate accusations of sexual assault.

In late August, federal Judge Douglas P. Woodlock ordered the University to allow a student-athlete—identified as “John Doe” in court documents—to enroll in courses this semester after finding that the University’s investigative model violated the principle of fundamental fairness. BC suspended Doe on June 18 after finding him responsible for sexual assault in violation of the University’s Student Sexual Misconduct Policy.

BC employs a “single investigator model,” in which either one or two investigators interview the accused student, the complainant, and any witnesses before compiling the evidence and sending a report and finding to the Student Title IX Coordinator and what was then the Dean of Students office. In Doe’s case, the investigators were Assistant Dean of Students Kristen O’Driscoll and external investigator Jennifer Davis.

The lawsuit arises as courts both in Massachusetts and across the country work to clarify how colleges and universities should conduct sexual assault investigations. Woodlock’s comments at the hearing suggest that Doe’s lawsuit could reconcile the different standards that private and public universities are held to.

This began with the 2000 Schaer v. Brandeis University case, where the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled that private colleges and universities have to provide students accused of sexual assault with “fundamental fairness.”

The decision drew on principles of Massachusetts common law, which holds that inherent in all contracts is a promise of fundamental fairness. The court upheld the argument that students and their universities agree to a contract, usually detailed in a student code of conduct or equivalent document. This ruling laid the groundwork for a litany of breach of contract and fundamental fairness lawsuits against institutions of higher education.

Private colleges and universities in other states argue that by following the procedure laid out in their student codes of conduct, they assure fundamental fairness. Private colleges and universities in Massachusetts, however, must show both that they followed their own procedures and that those procedures are fair.

Under the Obama administration, the Department of Education issued a “Dear Colleague” Letter in 2011 that reinterpreted Title IX, the federal civil rights law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs receiving federal financial assistance, issuing specific guidelines for colleges to use in their adjudication of student-on-student sexual assault cases.

As colleges adapted their investigation and adjudication procedures to the Dear Colleague Letter, several Massachusetts schools faced lawsuits alleging separate charges of breach of contract and violations of fundamental fairness—raising the yet-to-be answered question of what fairness actually requires when it diverges from student-college contracts.

In 2016, Doe v. Brandeis University became one of the most high-profile cases in Massachusetts to land in front of a federal judge. Brandeis University had employed the single-investigator model to determine that the plaintiff had sexually assaulted his ex-boyfriend several times over their 21-month romantic relationship. In court, the university’s lawyers argued that its Special Examiner faithfully followed the procedures detailed in Brandeis’ Student Handbook.

The judge ruled that while Brandeis had not breached its contract with the plaintiff, the investigation process lacked fairness. Brandeis had not permitted the accused student to see the charges levied against him, denied him a right to counsel, and prevented him from examining the evidence or witness statements.

But the ruling did little to define which procedures protect fundamental fairness in the college disciplinary process.

The pattern arose the next year in Doe v. Amherst College, in which a federal judge allowed a male student’s lawsuit alleging breach of contract and a violation of fundamental fairness—again, as separate infractions—to proceed. In that case, Amherst failed to consider exculpatory texts sent directly after the alleged assault.

Even more relevant to the current Doe v. Trustees of Boston College lawsuit is a case of the same name that appeared before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit in 2018. Drawing on the 2000 Schaer v. Brandeis University case, the First Circuit made a distinction between breach of contract and fundamental fairness claims, although ruled that the lower court should consider both separately.

“[Massachusetts is] the only state in the country that has that explicit requirement as a result of state litigation,” said K.C. Johnson, a Brooklyn College professor who chronicles Title IX litigation. “And what we’ve seen is that a couple of courts—the Brandeis court and the Amherst court—have essentially said that fundamental fairness means giving the accused student significant rights to defend himself. That is the equivalent of due process.”

Public institutions, however, have had to face a different standard: constitutional due process. On this front, Massachusetts has lagged behind other states in ordering schools to revisit their disciplinary processes—with the most recent example being Haidak v. University of Massachusetts Amherst, which the First Circuit Court of Appeals handed down last August.

Former UMass Amherst student John Haidak sued the university after a disciplinary hearing panel determined him responsible for assaulting his girlfriend while the two were studying abroad in Barcelona in 2013. Haidak argued that the University deprived him of due process and violated Title IX.

The First Circuit found that while UMass Amherst did unconstitutionally suspend Haidak because he was not provided with prior notice or a fair hearing, the university did not violate his rights in expelling him, as he was provided with a fair expulsion hearing.

Haidak had argued that his expulsion hearing was unfair, in part, because he was unable to directly cross-examine his accuser. The court ruled that due process in a disciplinary setting does require some form of real-time cross-examination, but that this questioning does not necessarily have to come from the students or their representatives.

In the hearing for the preliminary injunction, BC argued that Haidak, which occurred at a public university, did not raise questions of fundamental fairness. In response, Woodlock suggested that he sees the obligations of public and private institutions as “more or less the same thing.” His reading could set up a major shift in how private colleges and universities investigate sexual assault allegations.

BC also rejected the notion that its procedure wasn’t already in compliance with some level of cross-examination.

“With the assistance of counsel, Doe was able to comment on the evidence and point to any inconsistencies or gaps in the evidence that he perceived,” the University wrote. “This also gave him the opportunity to propose additional questions or areas of inquiry for the investigators to pursue. That the investigators did not deem additional information material to the outcome, or did not give any additional information the weight Doe would have preferred, is not actionable.”

At the hearing, Woodlock questioned the University’s single-investigator model, specifically with regard to credibility assessments in the absence of the real-time cross-examination of witnesses.

“What makes this case critical is that the First Circuit is going to have to decide once and for all, ‘What does, under Massachusetts State law, fundamental fairness, when adjudicating a Title IX case, mean?” Johnson said. “They won’t be able to avoid this question this time around, as they did during the first BC case.”

The First Circuit’s ruling, should it decide that single-investigator models without real-time cross-examination violate fundamental fairness, would upend college disciplinary processes in Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Puerto Rico.

When Woodlock explained his rationale for staying Doe’s suspension, he made a point of detailing the similarity with which he viewed the due process requirements in Haidak and the fundamental fairness question before him. He called BC’s lack of real-time cross-examination, or a robust substitute, a “fundamental deficiency” in the wake of the Haidak ruling.

“For present purposes, the considerations of due process that I have in mind are equally applicable in this context, to the private institution that is BC,” Woodlock said.

After staying Doe’s suspension, Woodlock also ordered there to be a new disciplinary process with both new investigators and the inclusion of real-time cross-examination.

Elsewhere in the country, single-investigator models like BC’s have fared much worse under the due process standard. The Sixth Circuit, which encompasses Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee, ruled in Doe v. Baum the University of Michigan’s single-investigator model violated due process in every case, as it lacked the opportunity for the parties to question each other directly.

U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos revoked the Dear Colleague letter in September 2017 under the basis that it “ignored notice and comment requirements, created a system that lacked basic elements of due process and failed to ensure fundamental fairness,” according to a Department of Education press release.

A study by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) conducted in 2017 found that college students were regularly denied the basic elements of a fair hearing. From the time the Dear Colleague Letter was issued to the

Under DeVos’ new Title IX proposal, colleges and universities would be required to hold live hearings with cross-examinations conducted by the parties’ advisers, although the complainant and respondent would not be allowed to engage in personal confrontation. Schools would also be prohibited from using a “single investigator” or “investigator-only” model, as BC currently does. These rules are not currently in effect.

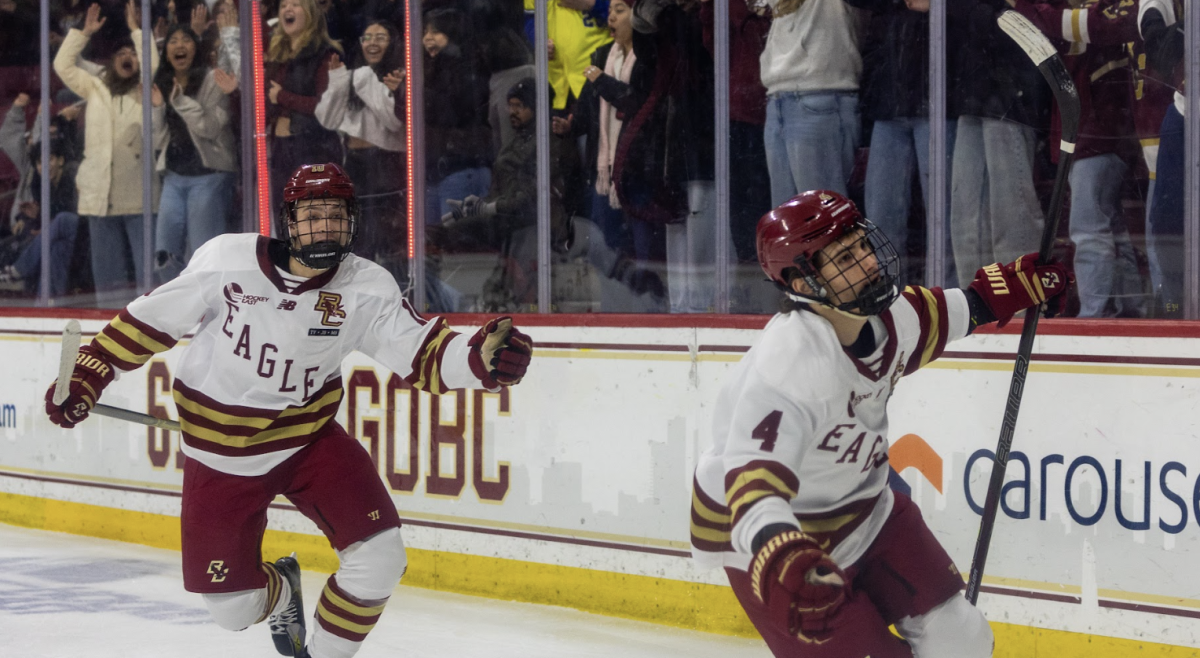

Featured Image Courtesy of Massachusetts District Court