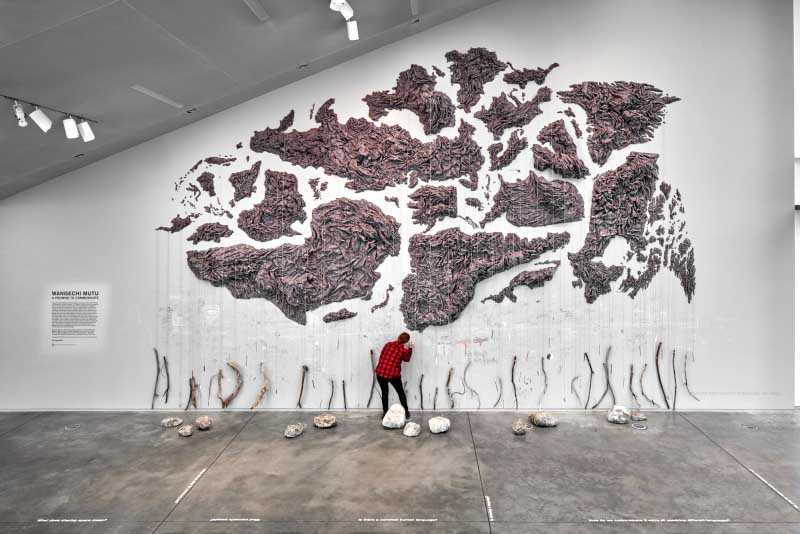

Wangechi Mutu’s exhibit A Promise to Communicate at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston tackles common perceptions of geographical orientation and its intersection with sociopolitical issues via a play on cartographic representation with a participatory element.

“[Mutu] was thinking about how technically we’re the most connected that we’ve ever been, but it also feels as if it’s the most divisive,” said Jessica Hong, assistant curator of the exhibit. “She wanted to create this space where everybody could express their thoughts, their views, and also communicate with each other.”

“Anyone can walk in and engage with the wall as they wish,” said Hong, alluding to the fact that the exhibit is in the lobby of the ICA.

This engagement comes in the form of various writing implements and an open space underneath the installation where anyone can add commentary.

This is all underneath a sculptural rendering of the world map mounted on the wall by Mutu. She approached the composition unconventionally, using the Peters Projection to size the land masses. Perhaps the most common iteration of the world map is the Mercator Projection, a rendering that severely underestimates the size of certain landmasses and overestimates the size of others. While the Peters Projection does address size, both it and the Mercator Projection apply a perception of north and south that puts many formerly colonized territories in the “global south.”

Mutu turns this on its head by using sculptural elements to capture the topography of a more realistic world map while adding a fantastical twist. Mutu used thick, woolen blankets made out of recycled materials to create the installation. These blankets are often used by aid organizations providing resources to “developing countries”— Hong emphasizes the problematic nature of this nomenclature— but also have use in galleries for packing.

According to Hong, Mutu invented the bunching technique used in stapling the blankets to the wall. This creates a riding that looks almost topographical and allows the piece to move more toward what a real rendering of a map would be. Mutu, however, moved some of the landmasses around in an artistic choice to emphasize certain aspects of history. Hong describes Mutu’s process in the installation.

“She[Mutu] was really planning it intuitively but also thinking about relationships between particular countries and continents,” said Hong. “The U.K., for example, is actually right next to the African continent which is on its side.”

The viewer can see that many land masses are not where they would traditionally be found on a map, but Mutu placed them on account of their history and interconnection with others in order to create a map that felt innate to her.

Mutu traditionally engages with “fantastical, futuristic, even post-apocalyptic collage work, particularly of feminine figures and Afrofuturism,” Hong said.

Additionally, she usually uses the gray material of the blankets as foreground, but here it is the main material.

Each landmass in the exhibit has a string hanging from it with a writing implement at the end. Mutu very intentionally tried to make sure each major faction had one in order to emphasize the multitude of perspective provided by the open forum for writing.

Some of these are attached to sticks, and there are additionally some writing implements attached to rocks at the base of the exhibit.

“She was thinking about that child nursery rhyme, sticks and stones can break my bones but words will never hurt me,” Hong said.

The participatory nature of the piece inevitably harkens to current events and questions of open communication. Before opening up to the public, the ICA staff had the opportunity to write on the wall. One of their quotes reads “my teachers and stuff didn’t believe in me now look my words are on a wall in a museum and it’s legal,” emphasizing the importance of a venue for open speech and communication. The staff also put certain prompts on the floor around the exhibit such that they are not part of the piece but do provoke thought in the participants.

People have drawn peace signs, hands coming together, and various other expressions of unity. There are of course the typical instances of seemingly off-topic scribbles such as simply “Lana del Rey” and further, “lasagna del rey.” That is not to impart a normative judgment on ideas presented in an open space, but to emphasize the freedom of expression of individuals participating. People are responding to others, building on ideas presented initially, and ultimately using this space to air what they feel is important.

The ICA has not yet had to remove any of the writing from the wall due to vulgarity, a fact which emphasizes the idea that giving people freedom of expression does not necessarily need to lead to intense negativity.

There are references to “s***hole countries,” cries of “Puerto Rico needs help,” and the hashtag “#BLM.” The piece is a product of its time because many use it as a direct reaction to current affairs.

“[Mutu is] going back to the idea of how we see the world as this flat expanse is how these notions of East and West arise,” said Hong.

She is challenging the way that the orientation of our maps impacts our thought while proving a space for people to speak their minds.

“These issues of race and power and survival are very much a part of [Mutu’s] practice,” Hong said. “In addition to the strong sense of materiality, there’s this notion of hybridity and global responsibility.”

So far the piece has been delivering on its “Promise to Communicate.” It will be up for about a year and will likely evolve with the times as it has in the past month or so since its opening to the public.

Image Courtesy of The Institute of Contemporary Art