The Department of Education (DOE) released proposed changes to regulations regarding the implementation of Title IX, specifically focusing on the response of educational institutions receiving Title IX benefits to cases of sexual harassment and sexual violence. The current Title IX guidelines set up under the Obama administration have been criticized as favoring accusers and denying the accused their right to due process.

Melinda Stoops, Title IX coordinator at Boston College, said that, at this point, no one at BC has sat down and discussed how BC might alter its policies, since these are just proposals.

Stoops emphasized that the changes are nothing more than proposals at this stage and are still subject to change. She did say that, while the policies may be altered, BC will retain its commitment to creating a safe campus.

“The priorities of everyone at this institution is to maintain an environment that’s free of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, and that’s not going to change,” she said. “We may have to change some of our practices in how we do that but our priority in creating a non-hostile environment—creating an environment that feels welcoming and safe—remains.”

The changes are largely intended to provide a more narrow definition of sexual harassment and bolster the rights of the accused. The current policy defines sexual harassment as any “unwelcome conduct on the basis of sex,” and the changes add that this conduct must be so “severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive” that it restricts the victim’s equal access to the institution.

K.C. Johnson, a professor at Brooklyn College who chronicles Title IX litigation, said he thinks the proposed changes more closely follow the spirit of Title IX.

The current regulations mandate that institutions use a “preponderance of the evidence” standard—whether the alleged harassment is more likely than not to have occurred—to determine responsibility for sexual harassment violations. This standard of evidence was chosen because the DOE had likened the grievance process to civil litigation, which generally uses the “preponderance of the evidence” standard.

The new DOE changes propose that institutions use either the “preponderance of the evidence” standard or the “clear and convincing” standard. “Clear and convincing” evidence is a level of evidence higher than a 50 percent level of certainty but requires less than the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard used in criminal trials. The DOE adds that the “preponderance of the evidence” standard may only be used if the institution applies this standard to respond to other code of conduct violations that carry the same maximum punishment.

Stoops said University officials aren’t ready to parse the document since changes could still be made.

“Where we’re at right now is really looking at not necessarily what we would do but the proposals itself and things that are relevant,” she said. “Once everything is finalized, then we’ll sit down and say ‘okay, what’s required for us to do?’ because we’re going to follow the law. And then, in cases … where you have a choice in the matter, then we will look at what makes the most sense.”

When these changes were first reported in September, concerned administrators and experts across the nation brought up examples of different schools across the country that had differing standards of evidence. In these cases, students would be held to different standards depending on what school they chose—or undoing progress that took place in regards to rights for victims of sexual violence that took place under the Obama administration regulations, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education.

The DOE proposal limits universities’ legal liabilities. In order for a university to have “actual knowledge,” the university’s Title IX coordinator or an official who has the authority to discipline these cases must be notified. Under this policy, if a professor or resident adviser does not report sexual harassment or sexual assault, the university is not legally liable.

R. Shep Melnick, a political science professor at BC who has written a book on the history of Title IX, said that the Obama administration went too far in requiring lower-level employees to report cases of sexual misconduct. For instance, he said that these employees should not be required to report cases of sexual misconduct they hear from third parties, as this is hardly more than “gossip.”

Melnick noted in a previous interview with The Heights that one of the most important aspects of the Obama-era policies was giving universities the opportunity to expand their Title IX offices. In a sense, the “bureaucracy” that was created will be here to stay regardless of changes to Title IX recommendations from the Executive Branch—especially if schools are being given the option to make changes rather than being required to do so by the Trump administration.

In that interview, Melnick also pointed out that the primary end goal of Obama-era recommendations was to reduce “retraumatization” from the process of filing a complaint pertaining to sexual violence. Melnick noted at the time that the inadvertent result of that pursuit has been a limitation on the rights an accused student has to fight allegations.

“For the Obama administration, the central goal essentially seemed to be to create a system that would encourage more people to report,” Johnson said in an email. He added that this “made discerning the truth a secondary goal.

“If … the central goal of the Title IX process should be to determine (to the best extent possible) whether the allegations are true, the policy proposals obviously will improve the process,” Johnson continued. “The key changes … will give the accused student a chance to test the merits of the allegation in a way that was not possible under the current system.”

The proposals also guarantee that those accused of sexual harassment may cross-examine their accusers through a chosen adviser.

“In most Title IX cases, which in the end depend on the credibility of the accused, [cross-examination is] absolutely vital,” Johnson said. “Its strong discouragement under the previous guidance was perhaps the single most unfair element of that guidance.”

This proposal has been the recipient of criticism, as some fear that this could discourage victims from reporting sexual violence.

Melnick said that he think cross-examination will make it easier to determine credibility in these cases, but does share the concern that could reduce the rate at which sexual misconduct is reported. Stoops said that she is not sure how cross-examination will affect victims of sexual violence because each victim is going to react differently to the sexual misconduct process. She noted, however, that she is aware of a lot of anxiety surrounding the proposal.

When asked whether the lack of cross-examination was fair, Stoops only said that it is in line with the law. She added that she looks at it through an “equity perspective,” and believes the current policy is equitable in that neither party currently has the ability to directly ask questions to the other.

The proposal does make some concessions to limit the harm to survivors of sexual violence.

“The proposed regulation balances the importance of cross-examination with any potential harm from personal confrontation between the complainant and the respondent by requiring questions to be asked by an advisor aligned with the party,” the document said.

Cross-examination may be done through a live video feed with both parties located in separate rooms, according to the document.

The Undergraduate Government of Boston College came out against the proposed changes Monday night. The group has concerns about the changes potentially allowing the University to not investigate sexual violence incidents, according to a statement released by the UGBC executive council. The group is particularly concerned about the ramifications of allowing cross-examination.

“We are deeply concerned that these proposed changes would significantly reduce campus investigations of sexual assault and unnecessarily disadvantage or retraumatize survivors in the process,” the executive council said in its statement.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has taken a strong stance against the proposed changes. It argued that the new definition of sexual harassment is too narrow and hard to meet and the standard of proof policy unjustifiably favors the accused. The ACLU also argued that the changes will relieve schools of the responsibility of responding to reports made to lower-level employees.

“The new rule inappropriately tips the scales in favor of the accused and against those who report sexual assault,” Louise Melling, ACLU deputy legal director said. “And the proposed rule would let schools ignore their responsibility under Title IX to respond promptly and fairly to such complaints.”

Conversely, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) has argued that the past Title IX regulations threatened students’ due process rights and has welcomed the steps that the current administration is taking in walking back many Obama-era policies.

“While not perfect, the proposed regulations indicate the federal government’s recognition that students accused of serious misconduct are entitled to meaningful due process rights, and the proposed regulations include a number of important procedural protections that will improve the integrity of the process for everyone,” Samantha Harris, FIRE’s vice president for procedural advocacy said.

Update (12/3/18, 9:09 p.m.): This article has been updated to include the UGBC Executive Council’s statement on the proposed changes to Title IX regulations.

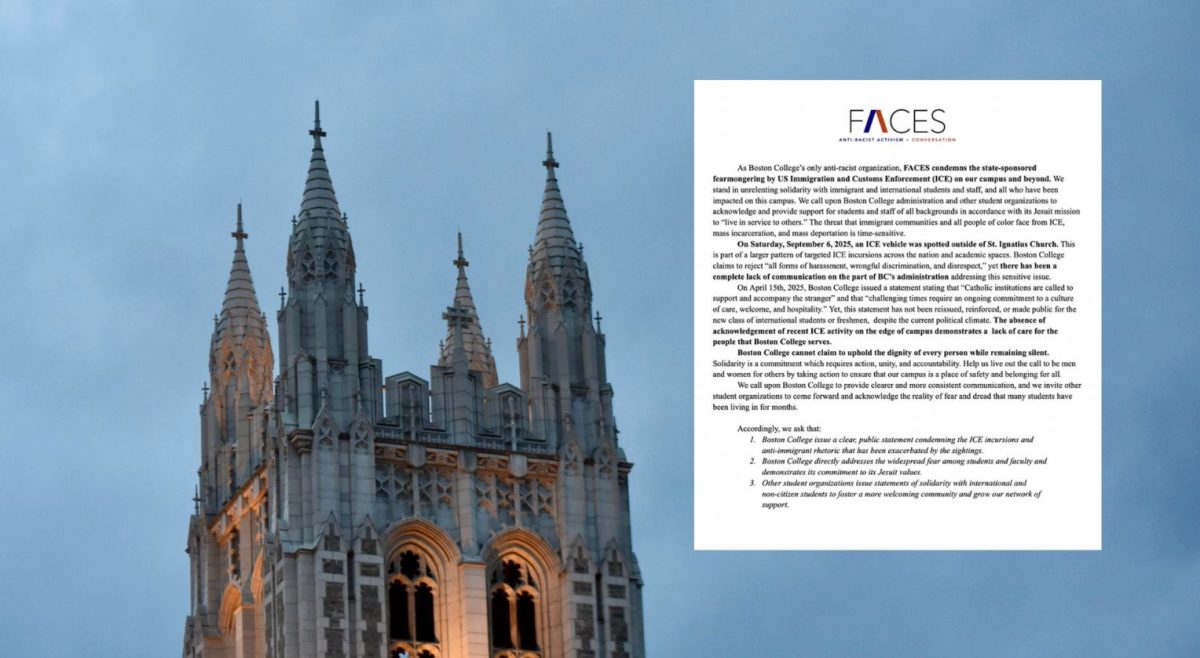

Featured Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons