As Boston College’s students, faculty, and administrators reacted to the racist vandalism in Welch Hall last December, cries for change spread across campus. But when everybody returned to campus in January, the conversation was was not what it once was. That disconnect between rhetoric and action inspired Phil McHugh, CSOM ’19, to step forward.

Frustrated with the outward-facing nature of the responses, McHugh sought to force organizations on campus to take concrete steps.

“I realized a lot of clubs, clubs that I was a part of, were so focused on what they would say and crafting the right statement,” he said. “It was all about, ‘What are we going to say, we have to get it out, we’ve got to post it on social media.’

“And I applauded that, I thought that was great. But then I was kind of like okay, we put out these statements, but then organizations felt resolved of all responsibility for actually doing anything.”

Under that mindset, the onus to respond inevitably falls to a handful of clubs, according to McHugh. The Undergraduate Government of Boston College, for example, passed an extensive resolution that the administration ultimately eschewed from adopting.

His first instinct was to reach out to Reed Piercey, UGBC president and MCAS ’19. He had already found his platform for change: a social media campaign, modeled in the style of the ALS Ice Bucket challenge, which went viral in 2014 and was led, coincidentally, by another Eagle: Pete Frates, BC ’07.

Piercy told McHugh to turn to FACES, an anti-racism organization on campus.

“So [the racist vandalism] happened first semester, and now it all feels a little bit complacent and normalized at school again,” Alina Kim, FACES council member and LSEHD ’20, said.

On Feb. 13, FACES posted a short, simple video describing their new social media campaign: the #RaceAgainstRacism. Three FACES council members—Kim; Nthabi Kamala, CSOM ’20; and Cameron Kubera, LSEHD ’20—sit together, describing the parameters of McHugh’s challenge.

Each nominee has 72 hours to complete the challenge, which asks that they publicize two short-term and one long-term actionable step toward fighting anti-blackness on campus. FACES vowed to hold an open council meeting to improve transparency, provide a resource guide to all faculty, and upgrade their website so as to increase their presence on campus.

“We seek to combat racism and its roots, oppression, and dehumanization through conversation, academic forums, and direct action,” Kim said in the video.

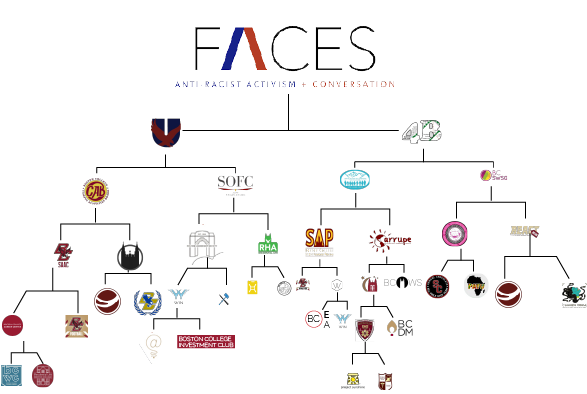

Over the next 11 days, the video gathered over 2,000 views and garnered responses from 40 different clubs, organizations, and even offices in the University. FACES nominated UGBC and 4Boston, a community service group—McHugh is a council member for the organization. The most recent round of nominees included the Office of Residential Life, the Public Health Club, and Presenting Africa to You (PATU).

“He wanted to do this very public social media challenge, and we all wanted that challenge to be about actionable steps, not just about creating a discussion or conversation about anti-blackness and racism on campus,” Kim said.

By tying participation to public statements, McHugh wants to ensure accountability.

“FACES is going to be following up after Spring Break to say, ‘Okay, you guys made these commitments [and] said you’re going to do this, so where are the action steps? Is it happening? Where are you in the process?’” he said. “It’s not about some statement to make the organization look good, but really holding them accountable to do what they say they’re going to do.”

Neither McHugh nor Kim know exactly how the check-in process might play out, although McHugh envisioned a combination of FACES members reaching out in private while publicly encouraging organizations to provide updates on the benefits of their changes.

“I think organizations maybe, on the down low, were making the steps they have already published though the challenge,” Kim said.

Another consideration was feasibility—a concern that gave form to the particulars of the Race Against Racism. The 72-hour window isn’t something Kim said he believed was “strenuous,” giving clubs enough of an opportunity to come up with intentional ideas rather than unrealistic or unimportant changes that could potentially be encouraged by a shorter turnaround.

Beyond turning discussion into action, the Race Against Racism also aims at shifting the language used to discuss incidents like last December’s.

“One thing that we’ve reviewed and been talking about a bit is we want this to be explicitly about racism and anti-blackness,” Kim said. “And we found that we tend to equate that maybe with diversity, inclusion, and multiculturalism. But I think that’s kind of the bare minimum in which we can talk about racism explicitly targeted against black students.”

Recalling his role in crafting a response for 4Boston, McHugh was struck by the responsibility large clubs have to incite change.

“We have this organization that’s one of the largest organizations on campus, we have this mission of social justice—promoting it both on campus and in the city at large—so what are we doing?” McHugh said. “This should be the type of issue that’s central to what our organization is.”

Carly Anderson, the campus minister in charge of 4Boston, echoed his sentiment.

“I think that the incidents of racial violence that have taken place on campus last year and this year and the response of FACES give us an opportunity to dig in a little deeper and take a closer look at what goals we have and what things we might want to brainstorm to continue reflecting on ways we can make all of our work more inclusive,” Anderson said.

In response to the challenge, 4Boston vowed to send its volunteers to existing campus programs on race, bias, and privilege—replacing a weekly small-group reflection. They also decided to create a Campus and Community Engagement Coordinator, who will be tasked with promoting diversity and inclusion in programming.

“This is the reshaping of a number of positions and this is a new responsibility,” Anderson said. “They will basically be a liaison in the same way all our leaders are liaisons without community partners. So it’ll be their responsibility to schedule meetings, say, ‘How are things going, how can we help?’”

4Boston turned around to challenge another community service group: Appalachian Volunteers of Boston College. Appa, as it’s more commonly known, sends BC students across the country to build and repair housing in needy areas.

“We started talking about things that had obviously been a part of the conversation from the first semester,” Diana Dinkel, a member of Appa’s formation committee and CSON ’19, said. “We didn’t have to reinvent the wheel. These things of race and bias and privilege and sexuality had already been part of the conversation.”

One short-term step they implemented—which had already been in the works—was adding reflections on biases, privileges, and racism throughout the service trip schedule. Like 4Boston, they also decided to send all participants to at least one culture club event per semester.

McHugh and FACES see potential for the Race Against Racism beyond Chestnut Hill, although no formal plans are in place.

“Alina, the first time we met, mentioned ‘We want to take this to other schools and see if they could make it happen,’” McHugh said. “So definitely that’s something we’re hoping to explore, especially as it gets to kind of bigger organizations at BC.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: The Heights has been challenged as a part of the #RaceAgainstRacism, and the paper’s response can be found on our social media accounts.

Featured Graphic by Ikram Ali / Heights Editor

Correction: 2/26/19, 12:14 p.m.): This article originally misspelled Reed Piercey and Diana Dinkel’s names. It has been updated.