Netflix’s favorite equine antihero returned on Friday for the first half of the season finale of adult animated comedy-drama series BoJack Horseman. Despite mixed reviews in its first season (67% on Rotten Tomatoes), the show soared to phenomenal ratings in its second season (100% on Rotten Tomatoes) and hasn’t looked back.

Its widespread critical acclaim and commercial success is due to its originality and honesty when grappling with hot-button social issues, such as celebrity culture, depression, gender roles, and addiction.

Season six begins much like those before it, with BoJack Horseman (Will Arnett) down on his luck, the depressed former sitcom star reluctantly checking himself into rehab. The season follows BoJack as he navigates rehab and mends broken relationships, while also showing flashbacks to his difficult childhood and time in the spotlight.

Characters like BoJack’s former agent and occasional girlfriend Princess Carolyn (Amy Sedaris), human ghostwriter Diane Nguyen (Alison Brie), and arch nemesis yellow Labrador Retriever Mr. Peanutbutter (Paul F. Tompkins) all return, bringing with them their own problems and a host of hilarious encounters.

When Bojack begins rehab in the first episode, he is given a speech on the 12 Steps about how committing himself to the steps will change his life. With every joke in BoJack, there seems to be a three-step process that occurs every time. The first step is hysterical laughter because the one-liners and scenes are just that funny. The second step is a tinge of guilt because the series tests the boundaries of humor with its gritty dark comedy. The third and most important step—the one that sets the series apart from basically all others—however, is the smart social commentary lying beneath the surface.

Diane and her cameraman, a buffalo named Guy (Lakeith Stanfield, one of many famous stars who make cameos in the show), investigate Jeremiah Whitewhale (Stephen Root) after his conglomerate acquires their online journalism project Girl Croosh. Diane tells Whitewhale she is going to expose his exploitative business practices after one of his employees dies on the job. Whitewhale happily replies that he murdered this employee, pointing to a newspaper article that legalized murder for billionaires and saying that the only way Diane can stop him is by becoming a billionaire and killing him herself.

At surface level, this is such an extreme case of hyperbole that one cannot help but laugh as the billionaire whale struts confidently around the room. Yet, like much of BoJack, these extreme cases of hyperbole serve as stinging satire, in this case that of income inequality in the United States. It points to a dystopian future that, after thinking about the rift between everyday Americans and the social elite, seems not so far away.

For much of BoJack, these extreme scenarios reveal uncomfortable and often sobering truths that many other television shows don’t grapple with. The absurdity of BoJack’s fictional world gives the writers more leeway to be assertive in their commentary because, after all, it’s a story of an alcoholic horse sitcom star.

Even when BoJack is not touching on social issues, its creators do not miss a beat with Easter eggs in almost every scene that require close viewing to appreciate. One could easily miss the painting on BoJack’s wall of a Vincent Van Gogh self-portrait with one exception: He’s a ram. Nods to literary works are also hidden in the dialogue, such as when an investigator of Jeremiah Whitewhale dramatically remarks, “Call me Isabelle,” spinning the famous opening lines of Moby Dick. The allusions are also relentless and are sometimes difficult to keep up with, as Isabelle immediately makes another literary reference, this time to The Great Gatsby.

Despite the wit, talent, and intelligence of the script, the show never feels pretentious or pedantic. This is BoJack’s greatest feat, as it provides smart commentary without force-feeding it to the audience. It succeeds in reaching every type of viewer, as anyone can gain something by watching it, even if it’s just a laugh. It avoids the criticisms of other shows such as Rick and Morty of being pseudo-intellectual because, despite its numerous layers, the central storyline is still about the character of BoJack and his undeniably hilarious life.

Creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg has crafted something utterly original with BoJack Horseman, and he doesn’t let his loyal fanbase down with this exciting first half of the season finale. And, regardless of the hilarity and edgy humor that pervades the show as always, fans will be happy to see some moments of tenderness between their complicated but beloved characters. BoJack even makes a list of people in rehab that he’s hurt and should apologize to. Who knew that a washed-up equine sitcom star could be so, well, human?

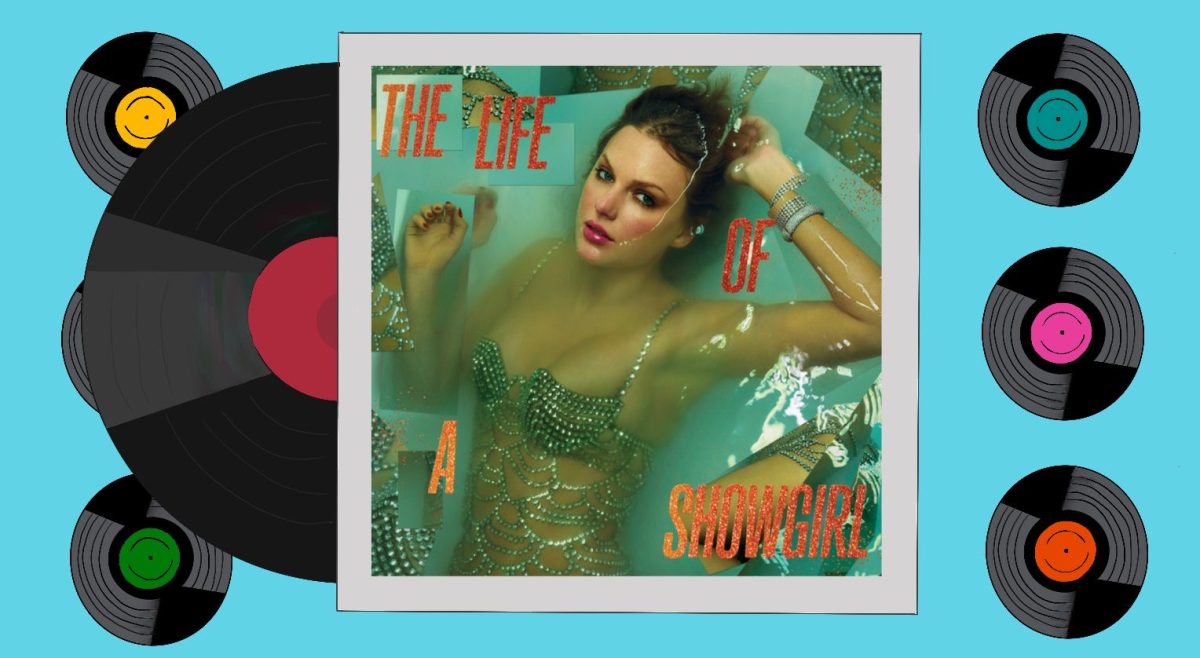

Featured Image by Netflix