Faculty within the Boston College political science department are considering creating an advisory board to oversee a controversial potential program backed by the Charles Koch Foundation.

The political science department voted to approve the potential collaboration with Charles Koch—the billionaire owner and CEO of Koch Industries, which manufactures and refines petroleum—last spring. A second vote, held at an October faculty meeting, approved a two-page “vision statement” for the program, which is now with the Office of University Advancement.

The vision statement, which was composed by members of the political science department, is titled “New Perspectives on U.S. Grand Strategy and Great Power Politics” and describes a program that would “challenge received wisdoms” and addresses the costs associated with current U.S. foreign policy.

The vision statement also lists several potential uses for the funds, including a lecture series, fellowships for graduate students, and a five-year joint hire in the political science department and international studies program.

Students in both majors have faced difficulty in class availability. Growth in political science majors have outgrown department hires in recent years, and the international studies program has a cap on the number of students allowed to enroll in the major.

Koch is famous for donating to conservative and libertarian think tanks, politicians, and scholars who favor and promote deregulation and climate change denial.

According to recent tax filings, the Charles Koch Foundation donated $5,000 to BC in 2015, 2016, and 2017, each time for “general operating support.”

Kay Schlozman, a political science professor, was the first to propose the creation of an advisory board to mitigate concerns that accepting funding could jeopardize the academic freedom of the department.

“Knowing that advisory boards connected to centers and institutes are common in academic institutions including at Boston College, and knowing that the proposal for Koch funding would probably generate controversy on campus, I suggested that my colleagues in International Relations might want to establish an advisory board once their project gets going,” Schlozman said in an email to The Heights. “The existence of an advisory board might help to defuse any conflict that might emerge over the matter of accepting funding from Koch.”

The advisory board, which would likely consist of faculty from both inside and outside the department, would monitor the program and report potential infringement on academic freedom, according to Gerald Easter, chair of the political science department. Easter said that the advisory board would also play a role in deciding whether to renew the agreement past its current five-year lifespan.

“The proposal is based on a five-year grant, so at the end of that time the advisory board, of course, would write a lengthy, thoughtful report, which would suggest whether the University should try to renew [the agreement],” Easter said.

Currently, the University has yet to submit a funding proposal to the Koch Foundation, according to Dean of the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences Rev. Gregory Kalscheur, S.J.

The decision about whether to implement an advisory board will lie with Kalscheur, as well as the political science faculty, who will vote on the proposal after it has been finalized.

“Given where we are in the semester, I do not expect a proposal to be finalized and submitted until the latter part of December or some time in January,” Kalscheur said in an email to The Heights. “An advisory board for the program is an idea that has been suggested, and it is a possible program feature that I am open to considering and implementing.”

The political science faculty has not yet met to discuss the prospect of an independent advisory board, according to Robert Ross—one of the political science professors spearheading the proposal.

“I think an advisory board, whether it’s warranted, necessary, or advisable, is something that needs to be discussed with the dean and the faculty,” Ross said.

Schlozman said that she suggested the idea after hearing about a similar body that Wellesley College introduced to oversee its Freedom Project, a Koch-funded speaking series and research program. Last year, The Boston Globe reported that Koch, along with his late brother David, had been encouraging ideologically like-minded donors to donate to specific programs to promote conservative ideas on campuses.

Following alumni and student pushback, Wellesley replaced the initiative’s director, overhauled the program, and created a “speech and inclusion” task force, according to The Boston Globe.

News of the department’s vote to approve has sparked a backlash on BC’s campus as well: Faculty for Justice, an informal faculty group, has been working to combat the proposal by circulating a fact sheet and petition, and over 100 people attended an anti-Koch protest on Thursday night. Senators in the Undergraduate Government of BC debated a resolution condemning the proposal, although they ultimately voted to table it for future discussion.

“The Koch Foundation has a bad reputation, that frankly, it has earned, with past experiences at other universities,” Easter said. “The one that everyone always makes note of is George Mason, so there were issues of academic integrity.”

At George Mason University, Charles and David had influence over committees charged with staffing the professorships that they funded. Similar situations have unfolded at Florida State University and Arizona State University following major donations from the Charles Koch Foundation.

At the October political science faculty meeting, one professor suggested listing climate change as an example national security threat in the vision statement as a way of testing how hands-off the Koch Foundation would be in regard to the curriculum, according to Easter.

“The faculty preferred instead to be general about what the program will accommodate,” Easter said. “They don’t want to explicitly write in what are the issues that will be addressed as a list, including climate change, which has direct security implications.”

Ultimately, the faculty overwhelmingly voted not to include the climate change-related language, according to several professors present at the meeting.

Ross said that adding the climate change language didn’t make sense if the vision statement didn’t also provide other examples of national security threats.

“In that context, it would be inappropriate to add specifically detailed issues,” Ross said. “[Not including the climate change language] is less of an issue of ‘we won’t do this.’ Those topics could certainly be raised in the speaker series, say.”

Easter clarified that that educational programs funded through the Koch Foundation would be allowed to address climate change.

“Climate change, as it relates to security studies, is on the table, just not in the vision statement, as an issue that can be addressed through the various manifestations of the program,” Easter said. “Speakers, publications, lectures.”

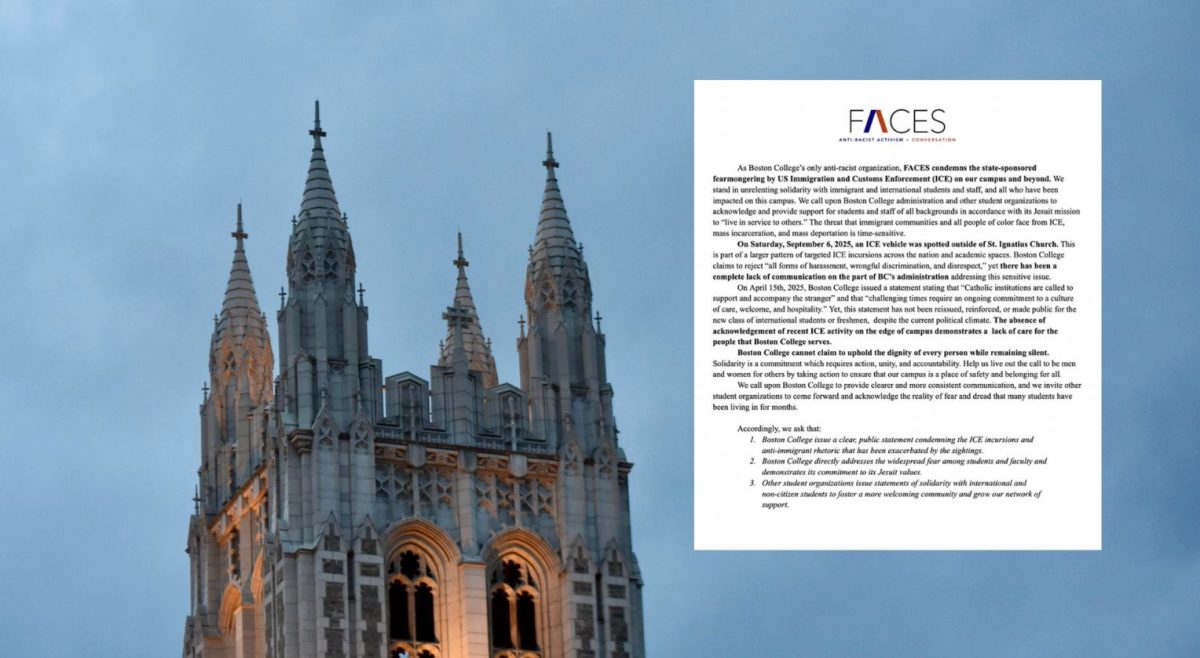

Featured Image by Celine Lim / Heights Editor