“That’s a big game, so [publicity] like that is kind of what we’re being pushed toward,” Kang said, MCAS ’22.

Two years after the storming of the football game and six months after Harvard community members filed a complaint calling for Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey to order the school to divest, Harvard University announced plans to cease investing in fossil fuels on Sept. 9.

In March, CJBC signed the 56-page complaint against the Harvard Corporation, which said the University failed to uphold its duty as a nonprofit to invest with charitable purposes.

Three months prior, various BC community members and scientists across the country filed a similar complaint requesting that Healey order BC to divest, saying the fossil fuel industry does not align with the Jesuit ideal of the “pursuit of a just society.”

“One of the main points of these lawsuits is being like, ‘Well, as a non-profit, you can’t invest this way because it’s not moral,’” Kang said. “So then, that was what was being brought up against Harvard and what’s being brought up against BC.”

Kang said she would like to understand how Harvard achieved this victory, as she is still holding out hope for Healey to order BC to divest.

“I would like to talk with people from Harvard just because I’m curious about exactly what happened,” Kang said. “But I think we’re still, you know, holding out hope for the attorney general’s office to move forward with the lawsuit.”

One obstacle to divestment is the relative lack of publicity that BC has in comparison to Harvard, Kang said, which she believes made divestment possible for Harvard.

“I think BC needs to work on having more student involvement and outside pressure,” Kang said. “I think Harvard, just because it’s Harvard, has a lot more pressure on it than BC does. They’re just way more publicly scrutinized than we are.”

As a Catholic institution, Kang said it makes sense for BC to cease investment in fossil fuels because the Pope has called on Catholics to divest. Kang also said that divesting is important because climate change is a matter of life and death.

“[BC is] profiting off the companies that are causing these, first of all, irreversible changes and deadly changes,” she said. “We’re not going to live … personally [I think] it is a matter of life and death.”

Kang said because there is a limited supply of oil left in the world, investing in fossil fuels is not a fiscally sound decision for the University to make.

BC historically isn’t at the forefront of such policy changes, Kang said.

“BC has never been on the cutting edge of anything,” she said. “At this point, no matter what they do, they’re just playing catch up to Harvard.”

Boston University announced on Thursday that it will immediately begin divesting from fossil fuels, citing a growing list of schools, including Harvard, that have made plans to divest. BU’s Board of Trustees voted Wednesday night to move away from investing in fossil fuels, acknowledging the rapid acceleration of the climate crisis.

BC’s investment decisions are set by the Board of Trustees, and the University believes divestment is not an effective way to address climate change, according to a University statement.

“While University investment in fossil fuel companies is minimal, BC is opposed to divestment on the grounds that it is not an effective means of addressing climate change,” the statement reads.

BC uses its endowment—which totaled $2.6 billion as of May 31, 2020—to provide funding for financial aid, faculty chairs, student programs, and academic and research initiatives, not to promote social or political change, according to the statement.

“The University’s position remains that the best way to respond to the important issue of climate change is for Boston College–along with corporations, organizations, and individuals–to take action to reduce energy consumption and enhance sustainability measures,” the statement reads.

CJBC and various clubs are planning a divestment town hall to raise awareness and activism in the student body, Kang said.

“We’re going to have different clubs come and we’re going to talk about divestment,” Kang said. “I think a lot of the issue on campus also is that maybe people aren’t super aware of what divestment is, or even the fact that BC has invested in fossil fuels, so that is definitely the goal for the start of the year.”

Kang’s activism during her four years at BC and her involvement in the greater fight for divestment has been tiring, she said, but she still remains committed to her work. Anger keeps her motivated, she said.

“I’m just angry at this point,” Kang said. “I’ve invested my time in this.”

Siobhan Pender and Alec Goos, co-presidents of EcoPledge of Boston College and both MCAS ’22, wrote in an email to The Heights that they are encouraged by the steps Harvard has taken to move in a more sustainable direction.

“We believe, given that Harvard has the largest endowment of an estimated $42 billion, that it is important to see its divestment from fossil fuels as a major step in the shift towards a low carbon world,” the email reads. “We hope this progress continues with other similar endowments, and as environmentalists, we hope to see BC making more sustainability progress in the future, whether it’s through divestment or through shareholder engagement.”

Though she is enthusiastic about Harvard’s plan to divest, Kang said she is not optimistic about BC doing the same. Regardless, she hopes others will recognize that divesting is possible.

“I would love to see BC … take a note from Harvard,” Kang said. “Am I thinking that’s gonna happen? No, but I hope that it shows people that it’s possible.”

Update 9/24/21 2:10 p.m.: This article has been updated to include BU’s announcement to divest from fossil fuels on Thursday.

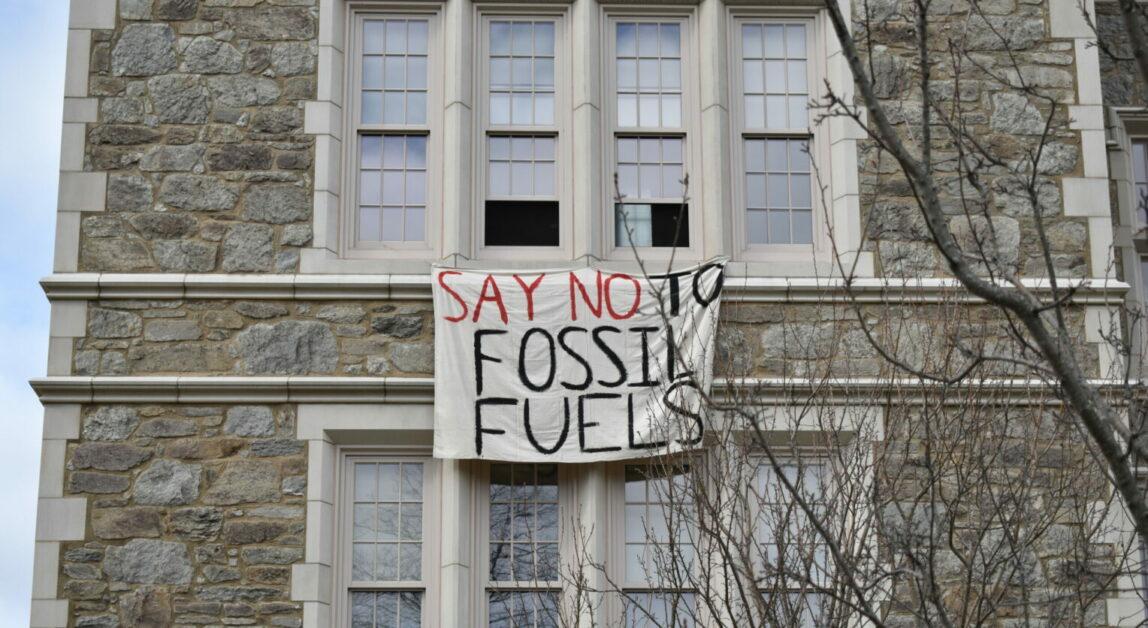

Featured Image by Vikrum Singh / Heights Editor