An endowment is a group of donations given to a school to support its educational mission. Schools then invest this money to further develop the endowment, ensuring future financial stability.

The main goal of an endowment is to provide a buffer against economic fluctuations, according to Thomas Parker, senior associate emeritus at the Institute for Higher Education Policy.

“I have to say that one of the primary functions of an endowment is to provide a financial buffer during bad economic times,” Parker said. “And that’s been the most important factor in most of the outstanding universities in America, in their ability to survive and to be outstanding.”

Endowments typically have strict rules on what money can be spent, with most schools never touching the principal balance, but only the interest that builds each year. Most modern endowments invest in a variety of assets, like stocks, bonds, and real estate, among others.

Timeline of BC’s Endowment

In 1970, BC students went on strike. The University had announced it was raising tuition by $500—a sizable amount at the time—and students were outraged. One cause of this tuition raise was the University’s precarious financial situation.

“It was ‘significant deficits’ in fiscal years 1969, 1970, 1971, and 1972 which brought the University to the brink of financial ruin,” an administrator told The Heights in 1973.

As BC struggled to overcome these budget deficits, it faced another problem: a comparatively small endowment. A Heights article from 1970 reported that while Harvard University’s endowment was over $1 billion, BC’s was just $5 million.

In 1980, BC decided to implement a new investment strategy that would focus on the future instead of immediate operating costs. John Smith, financial vice president and treasurer at the time, said that BC would reinvest most of the endowment’s income and buy growth stocks. He hoped this method would average an endowment growth of 15 percent per year, not including gifts.

“Smith believes an endowment fund should provide academic enrichment through the establishment of chairs, provide scholarships for needy people, benefit the physical plant, assist the school in times of financial need, and enhance the whole balance sheet,” reads a Heights article from December of that year. “But, Smith says BC’s $8 million endowment fund is ‘too’ small to perform adequately.”

BC no longer discloses its investment portfolio, but a Heights article from 1980 showed the shares BC had in oil companies at the time: 3,200 in Exxon Corporation and 1,200 in Royal Dutch Petroleum.

BC’s endowment experienced bumps in subsequent years—such as a dip in the endowment following the stock market crash known as ‘Black Monday’ in 1987—but by 1995, BC’s endowment had increased to $447 million, ranking first among the nation’s Jesuit colleges. Passing the billion dollar mark in 2000, BC’s endowment had doubled in value since early 1995.

Recent Developments

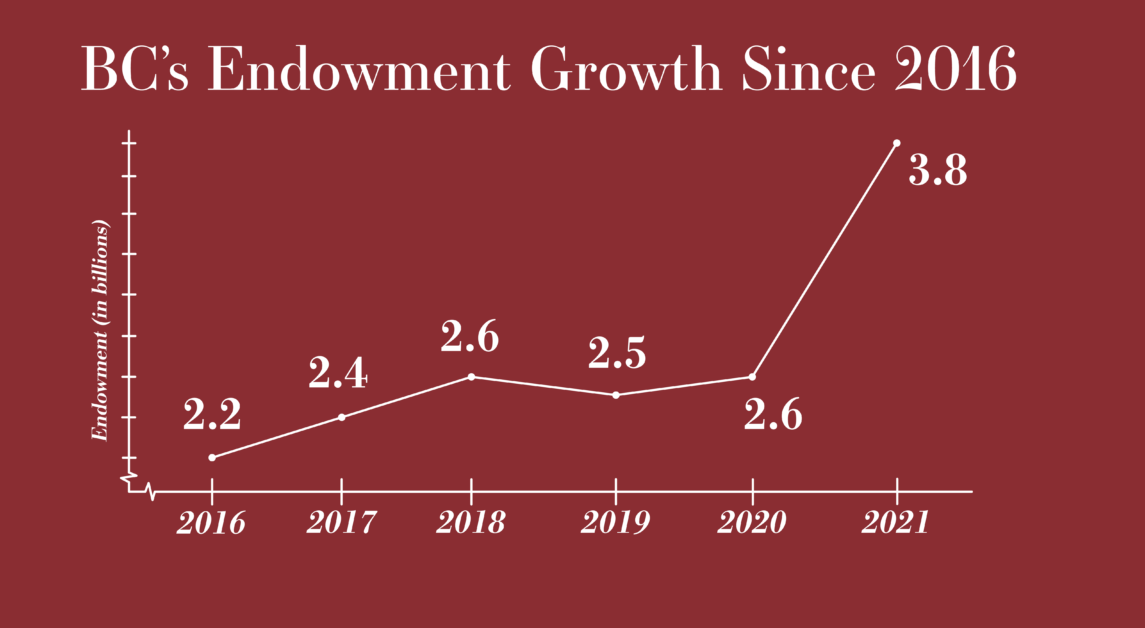

In the past fiscal year, BC’s endowment jumped by around $1.2 billion, bringing the endowment’s total to $3.8 billion. This 46 percent increase reflects a year of broad endowment growth for colleges nationwide, though BC performed particularly well, with gains 19 percent above the median.

This increase is significant compared to recent growth—the endowment was $2.2 billion in 2016, $2.4 billion in 2017, $2.6 billion in 2018, $2.5 billion in 2019, $2.6 billion in 2020, and now, $3.8 billion.

“This year’s increase was attributable to a strong market and the excellent leadership of the Investment and Endowment Committee of the Boston College Board of Trustees and BC’s Chief Investment Officer John Zona,” wrote Senior Associate Director of Communications Ed Hayward in an email to The Heights.

A BC Perspective

Peter Ireland, professor in the economics department at BC, said that because the main source of funds for endowments is philanthropy, endowment management is done with the goal of managing lumpy payments to ensure that the expenses paid out of the endowment are smooth.

“You don’t want the fitness center to be open one year and have to close down partially the next,” Ireland said.

He cited three reasons why philanthropic donations to BC’s endowment fund are inconsistent.

Firstly, major donors to BC, such as the Lynch family or the Fish family, do estate planning periodically, so they normally donate to the University at those times.

Additionally, while the University runs capital campaigns every five to seven years that bring money into the endowment, it is limited in how often they can run such campaigns, Ireland said.

“You can’t go to donors every year and say, ‘It’s really important this time,’” he said.

Lastly, for the vast majority of donors, their willingness to donate to the endowment annually normally depends on the economy and the stock market.

“In the December of a great year where you got a big raise and the market [has] gone up, you’re happy to give money,” Ireland said. “In years when the market goes down and you’re worried about maybe even losing your job, you’d like to give more money but you’re just not going to.”

Implications of the Increase

Ireland cited BC’s large endowment growth this year to a mixture of well-placed investments and the strength of the stock market.

“Even if it was simply stocks, it was a great year for the BC endowment,” he said.

While the pandemic brought challenges to the economy, Ireland said this past year’s growth was a silver lining. He also said, however, that this stark increase is not reflective of future endowment growth for BC.

“What managers of the fund and what trustees have to keep in mind is that this is a huge return one year which is unlikely to be repeated and would have to be averaged out over time,” he said.

Parker echoed a similar sentiment, emphasizing how an endowment’s success can only be determined in the long run.

“It’s a race of decades and even centuries,” he said. “It’s how endowments perform over the long run. That’s what counts in the end. … Every year when the endowment results come out, everybody wants to say, ‘Oh, let’s rank them one to 100,’ but that doesn’t really make any sense in terms of if you’re trying to evaluate the effectiveness of an endowment over time.”

Ireland said that overall, a larger BC endowment is good for students.

“Superior performance of the University’s endowment means more money for scholarships, less tuition increases for all students,” he said.

Another benefit of a large endowment increase is more support for diversity programs, according to Parker.

“One of the things that endowments buy, which is often overlooked, is diversity,” Parker said. “Endowments subsidize an institution’s ability to offer financial assistance. Without that, you can’t really have a robust diversity program.”

Fossil Fuel Divestment

As for sustainability, Ireland said the University’s decision to engage in non-environmentally sustainable investments has been a long-standing issue, especially due to the potential conflict with the University’s broader Jesuit mission.

“So, it’s always the case that these different goals have to be balanced off against one another,” he said.

He said that the University’s investment decisions related to sustainability is not what led to the endowment growth.

“No matter what their view about environmentally sustainable investments or … reconciling the University’s mission with funds management would be, BC still would have done very, very well,” Ireland said.

Student organizations, including Climate Justice at BC, have long called on the University to divest from fossil fuels, and the University has consistently denied their requests.

After the Vatican called on Catholic institutions to divest, BC responded that as a private institution, BC’s investment decisions are made by University leadership and the Board of Trustees. The University has also emphasized its position that divesting from fossil fuels is not a viable solution to climate change.

“The endowment exists to provide a permanent source of funding for financial aid, faculty chairs, and student programs, as well as the University’s academic and research initiatives, and is not a tool to promote social or political change, however desirable that change might be,” the University told The Heights in December.

Calls for divestment from fossil fuels, however, aren’t BC’s first conflict regarding divestment. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, BC faced controversy over investment ties to companies in South Africa amid Apartheid. Student groups and activists called on “BC to divest itself of corporations with holdings in South Africa,” according to a Heights article from 1978.

Then-University President Rev. J. Donald Monan, S.J., announced in 1985 that BC no longer held stock in companies that did business in South Africa. In a Heights letter to the editor, Monan wrote that BC had available investment opportunities of at least the same value as its last remaining securities within South Africa, so the retention of these stocks would not help nor harm the University financially.

“The sale of our few stocks of companies doing business in South Africa was not intended to be a policy statement, in the sense of constituting a moral judgement against companies that have some business operations in South Africa, nor, consequently about the morality of holding investments in those companies,” Monan wrote.

Monan followed this statement by emphasizing the moral insustainability of the governmental policy of Apartheid.

If the University eventually decides to divest, Parker said, the best way to approach the process is a long-term phasing out of fossil fuel-related holdings.

“Divestment could be done in an orderly way, and Harvard has begun to take some steps in that direction, and some several others,” Parker said. “I think, sooner or later, all major endowments will have to make some kind of adjustments for fossil fuel issues. I just think that … it’s not in the best interest of either the people who want divestment or the people who are investing to do wholesale selling over a short period of time.”

Featured Graphic by Olivia Charbonneau