This is the second installment of a two-part series about sustainability and the climate change conversation at Boston College.

Instead of urging people to have a perfect, zero-waste approach to reducing their carbon emissions, institutions should encourage individuals to consider the importance of sustainability, César Baldelomar said.

“It’s impossible to be totally carbon neutral,” said Baldelomar, a visiting lecturer and doctoral candidate in the School of Theology and Ministry. “But you know, you can make concerted efforts to try to, and so I think that something our institutions can do better is trying to get us to not care, but actually feel like we are a part of this.”

Boston College highlights the importance of sustainability with its environmental studies and global public health programs. And through various sustainability initiatives across Facilities Management and BC Dining, conversations about the environment are also prominent outside of the classroom.

But students and the University remain divided about the issue of divestment—the removal of investment capital from oil, coal, and gas companies for moral or financial reasons.

Globally, 1,599 institutions have divested, contributing to an approximate $40.5 trillion being directed away from fossil fuels. Of these divested institutions, 35.7 percent are faith-based organizations and 15.9 percent are educational institutions, according to the Global Fossil Fuel Commitments Database.

Boston Mayor Michelle Wu, scientists, politicians, and advocacy groups denounced the BC Board of Trustees’ investment in fossil fuel stocks in a 2021 letter to then–Attorney General Maura Healey.

“As concerned students, faculty, politician leaders, civic groups, and community members, we ask that you investigate this conduct and that you use your enforcement powers to order the Trustees of Boston College to cease their investments in fossil fuels,” the letter reads.

Amid differing opinions about the University’s investment policies, BC has not divested from fossil fuels. BC’s endowment—including its investment tied to fossil fuels—has enhanced the University’s funding for vital programs, according to a statement to The Heights in 2020.

“The endowment exists to provide a permanent source of funding for financial aid, faculty chairs, and student programs, as well as the University’s academic and research initiatives, and is not a tool to promote social or political change, however desirable that change might be,” the University told The Heights.

But as global temperatures rise and advocacy groups question BC’s adherence to Catholic teachings on sustainability, some students and faculty told The Heights that their concern about divestment is growing.

The Decades-Long Divestment Conversation

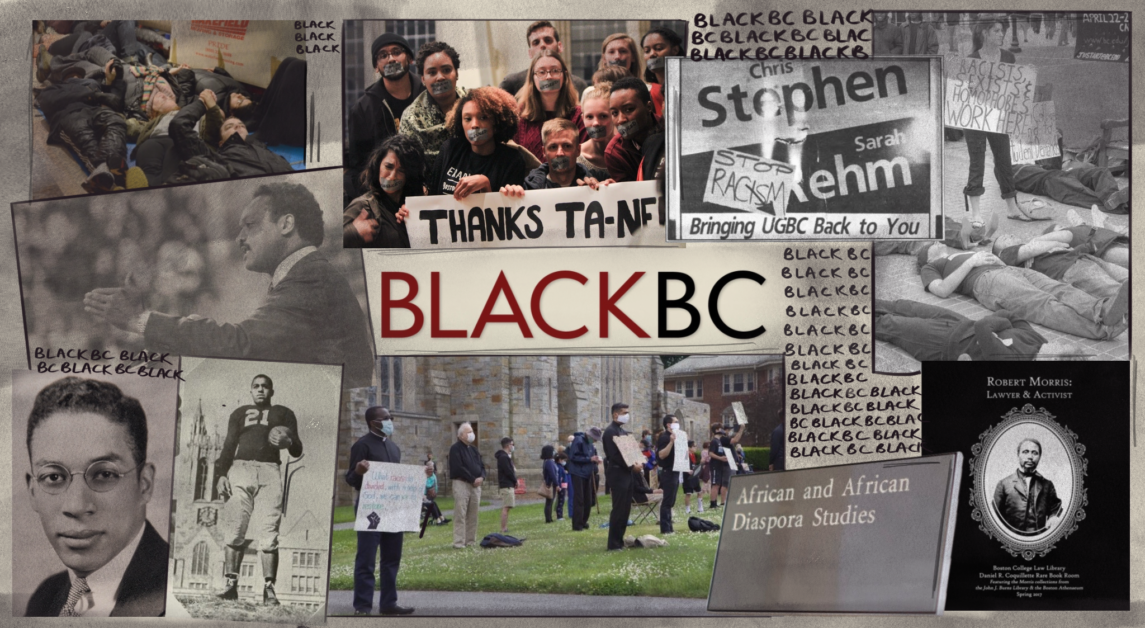

BC students and community members have called on the University to divest from fossil fuels for decades.

In the past, the University has adapted its investment approach following student pressure to re-evaluate. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the University pulled its investments from companies in South Africa amid Apartheid after student groups and activists called on “BC to divest itself of corporations with holdings in South Africa,” according to a Heights article from 1978.

Then–University President Rev. J. Donald Monan, S.J., announced in 1985 that BC no longer held stock in companies that did business in South Africa.

In 1992, conversations about divestment began to focus on the climate crisis and BC’s investment in fossil fuels. When Richard Cooper, a Harvard professor of international economics, gave a lecture on global warming, the University received criticism for its fossil fuel investments. And calls for change continue today.

Molly Caspar, treasurer for Climate Justice at Boston College (CJBC)—a student organization that advocates for environmental justice issues—said the club has contacted and spoke with different BC administrators for many years to advocate for divestment. CJBC is usually disappointed with these interactions, Caspar, MCAS ’26, said.

“We’ve heard pretty discouraging opinions about how [administrators] don’t plan to divest—they don’t have plans, so that is not something they’re interested in,” Caspar said.

CJBC was founded in 2012 under the original name BC Fossil Free, according to Caspar. The University approved CJBC as a registered student organization in 2015, and it has hosted registered rallies and protests in the years since.

Since 2015, tensions have risen between the University and CJBC members. In 2017, BCPD officers threatened CJBC members with disciplinary consequences after they protested outside a Pops on the Heights gala, according to a timeline created by CJBC.

During the 2022 Hosting Earth Conference, former President of Ireland Mary Robinson advocated for BC and other universities to divest from fossil fuels.

“I think universities should be leading on this issue in every sense because there is a crisis,” Robinson said at the conference. “I have for a long time supported the idea of universities including my alma mater, Harvard, divesting.”

In February of 2022, the University put CJBC on a year-long probation after the club delivered cards with vulgar language to University President Rev. William P. Leahy, S.J., as a part of a Valentine’s Day–inspired divestment protest calling on the University to “break up with fossil fuels.”

“Climate Justice of Boston College delivered to the President’s Office a number of ‘valentines’ that used extremely vulgar and offensive language,” said Tom Mogan, then–associate vice president for student engagement and formation.

Caspar said CJBC planned to hold a “divestment town hall” last year on campus. Despite CJBC’s plans, Caspar said the University strongly discouraged CJBC from using the word “divestment” in the event title. The Office of Student Involvement then changed the event title to an “environmental justice town hall”—an act that Caspar said completely changed the marketing and purpose of the event.

“In general, the administration is very unreceptive to the work that we do,” Caspar said. “And it doesn’t feel like they care, and usually feels like they’re intentionally trying to ignore the work that we do.”

Last month, seven climate advocates—including

CJBC members and two members of St. Ignatius of Loyola Parish’s “Green Team” gathered outside of Leahy’s office with candles in their hands, dropping off a paper copy of Laudate Deum, Pope Francis’ most recent apostolic exhortation on the climate crisis.

“We are here to support these students who have been asking for a long time for BC to take seriously their Jesuit values and the Catholic values for social justice,” Strad Engler, Green Team member, said.

Despite the difficulties the club faces in pushing for divestment, Caspar said that CJBC’s efforts are still important.

“I think even as discouraging as it can be at BC sometimes with how unreceptive they are specifically to issues of divestment, I think that it’s still a very, very, worthy fight and worthy cause because this is not something that’s gonna go away,” Caspar said.

Philip Landrigan, director of the program for global public health and the common good, said there is an increased number of courses discussing the climate crisis within the global public health and environmental studies departments. This motivates more students to become involved in environmental efforts on and off campus, he said.

“I think students in [this] generation are very, very deeply concerned about climate,” Landrigan said.

Aligning With Jesuit, Catholic Values

Baldelomar, a visiting lecturer and doctoral candidate in the School of Theology and Ministry, said that commitment to the environment is deeply rooted in Catholic doctrine.

“Now this is central to Catholic faith and Catholic teaching, and that’s why I think Francis is, you know, kind of peeved in some ways,” Baldelomar said.

Although Francis has encouraged Catholics to embrace sustainability as a part of Catholic social doctrine, Baldelomar said Francis is facing pushback from Catholics in the United States who are hesitant to change their financial investments due to deeply seeded political divisions.

“A Pew survey that came out said that Catholics are no more likely in the United States than just other Americans to follow ecological teachings or ecological sustainability, or even think that climate change is a threat,” Baldelomar said. “This is, again, very concerning, given that the pope has been honing in on this theme.”

Pope Francis published Laudato si’ in 2015—a papal encyclical calling for action against climate change.

Five years after releasing Laudato si’, the Vatican called on Catholics to divest from companies and industries engaged in activities “harmful to human or social ecology” and the environment.

On the five-year anniversary of Laudato si’, BC rejected the Vatican’s call.

“As a private university, Boston College’s decisions regarding investments and governance are made by University leadership, in concert with the Board of Trustees,” Associate Vice President for University Communications Jack Dunn said in an email to The Heights in 2020. “While we welcome the Vatican document, our position regarding divestment remains unchanged.”

In response to BC’s decision, CJBC wrote a statement about the University’s position on divestment.

“In a major development yesterday the Vatican called on Catholics around the world to divest from fossil fuels,” the statement read. “The debate CJBC has been having with the administration of BC for over 7 years is now over. There can be no more obfuscating or denying BC’s moral obligation to take action. It is time to divest.”

Baldelomar said that Francis’ latest statement, Laudate Deum, demonstrated the pope’s concern with the U.S. church, and, more specifically, the role of climate deniers in the face of the world’s most existential threat.

“His latest statement goes after the climate deniers in particular,” Baldelomar said. “And he really pushed back and said, you know, climate deniers have no place in policy and they have no place in our religious institutions.”

Caspar said that especially at a Jesuit, Catholic institution, she thinks that the University has an obligation to listen to Pope Francis’ suggestions.

“I think that it’s disappointing that as a Jesuit, Catholic institution, we’re kind of choosing to ignore [divestment], but not also ignore, almost intentionally suppress voices on campus that are arguing for this,” Caspar said.

BC’s Status Among Other Divesting Universities

Students’ and theologians’ calls for divestment go beyond the BC community—pressure to divest has emerged at Catholic campuses across the country in recent years.

In February 2020, students at BC and 57 other universities, including seven Jesuit institutions, took part in the Fossil Fuel Divestment Day (F2D2) campaign—a day designed by the United Nations to draw attention to the importance of divesting.

Like BC, universities such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Northeastern University, and the University of Texas at Austin have not announced plans to divest.

In 2021, Boston University announced its decision to divest from fossil fuels, citing increasing proof of the harmful effects of burning fossil fuels on the climate and the advocacy of climate activists as reasons for its decision.

“This has been a long journey within the BU community and the Board of Trustees,” Robert A. Brown, BU university president, told BU Today. “This is putting us on the right side of history.”

And this fall, NYU announced in a letter that it would avoid direct investments in fossil fuels—of which it currently has none—and avoid indirect investments in fossil fuels after a push from Sunrise NYU, a student environmental group.

“New York University and Sunrise NYU both recognize climate change’s threat to our community and the world, and we recognize and appreciate that the combustion of fossil fuels is a significant contributor to climate change,” the letter reads.

Georgetown University, another Jesuit university, adopted a policy on fossil fuels, reflecting a commitment to sustainability, according to its website.

Georgetown’s Board of Directors passed a divestment resolution in 2015, and then it approved another investment strategy policy in 2017 of “commitment to social justice, stewardship for the planet, and promotion of the common good,” according to the University’s website.

Caspar said that because BC is a leading American university in scholarship about innovation and the environment, it should follow the lead of universities similar to BC—including Georgetown—that have divested.

“If Georgetown can do this also—as a Jesuit, Catholic institution—then this is something that we should be looking to them for,” Caspar said.

Baldelomar also said that BC’s Jesuit values should motivate the University to follow Francis’ teachings, especially because Francis is a Jesuit himself.

“And, you know, especially Jesuit values right, I think should be aligned with this message,” Baldelomar said. “And also given that the Pope is Jesuit, institutions like BC I think should be taking a lead on this and following Francis’ teachings.”

Landrigan also emphasized his support of divestment as both a scientist and a member of a Jesuit institution. He said the decision to divest is—both scientifically and morally—the correct one.

“My own view is that BC should divest from fossil fuels,” Landrigan said. “The National Academy of Sciences, which is the nation’s leading scientific authority, just came out with a statement the other day saying that they are going to be going through all their investments and divesting from fossil fuels.”

Religious values aside, Baldelomar said higher education institutions should recognize their active role in “advancing” or “deferring” catastrophic climate events that will result from rising global temperatures and pollution. But this can be difficult, Baldelomar said, due to differing priorities of the corporate and private donors that universities like BC often rely on.

“And so we also have that to contend with and that’s just the reality of not just Catholic institutions, but all institutions across the world,” Baldelomar said.

Landrigan said BC students have demonstrated a deep concern about the climate and should continue to involve themselves in environmental efforts on and off campus.

“Keep talking,” Landrigan said. “Keep impressing on the elders the importance of the issue. The fact that your generation is going to have to live with [climate change] for a lot longer than we do. And keep making the argument that climate change has to be taken seriously, especially in a Jesuit Catholic University.”