During a dark and grim history, certain wordsmiths in Ireland have given voice to the human condition, experienced by everyone who has experienced hardship. Famously demonstrating a keen and introspective view of the Irish world, poet William B. Yeats, elegantly brought Irish literature into the 20th century. Aptly and with unmistakable ardor, Yeats reflects on country, family, love and youth with words that deeply capture moments in his life and in the history of Ireland. The modest exhibit on show in O’Neill Library this September does not fail to snap a compelling picture of Yeats passionate art. Sure to leave readers amazed at his lyricism, Yeats never fails to craft “the intellectual sweetness of those lines, that cut through time or cross it withershins”.

Coming from the panoramic vistas and low lying plains of Ireland, Yeats was born to John Butler Yeats and Susan Pollexfen on June 13th, 1865. From a young age, he was exposed to the beauty of Irish artistry through both his parents. His father was a painter and his mother often entertained Yeats and his siblings with Irish stories and folk tales, which undoubtedly nurtured his later fixation on the subject. From Dublin to London, Yeats was schooled and influenced by the changing world around him. Marked by the decline of the Protestant Ascendancy and the later executions of separatists during the Easter Rebellion of 1916, Yeats was armed with plenty of munitions to articulate the sentiments he and those like him held during this transitional period. All his work examined more complex thoughts and feelings, blending the trials and turmoil of his time with ideas of mythology, the occult and spiritualism. These threads can be seen throughout his works and in many ways make his pieces timeless in nature. Unlike other contemporary Irish writers like James Joyce, who left Ireland for good in 1912, Yeats embraced his native country, returning later in life. Becoming an influential member of the Irish Senate, he helped pass legislation preserving the Irish identity in the arts.

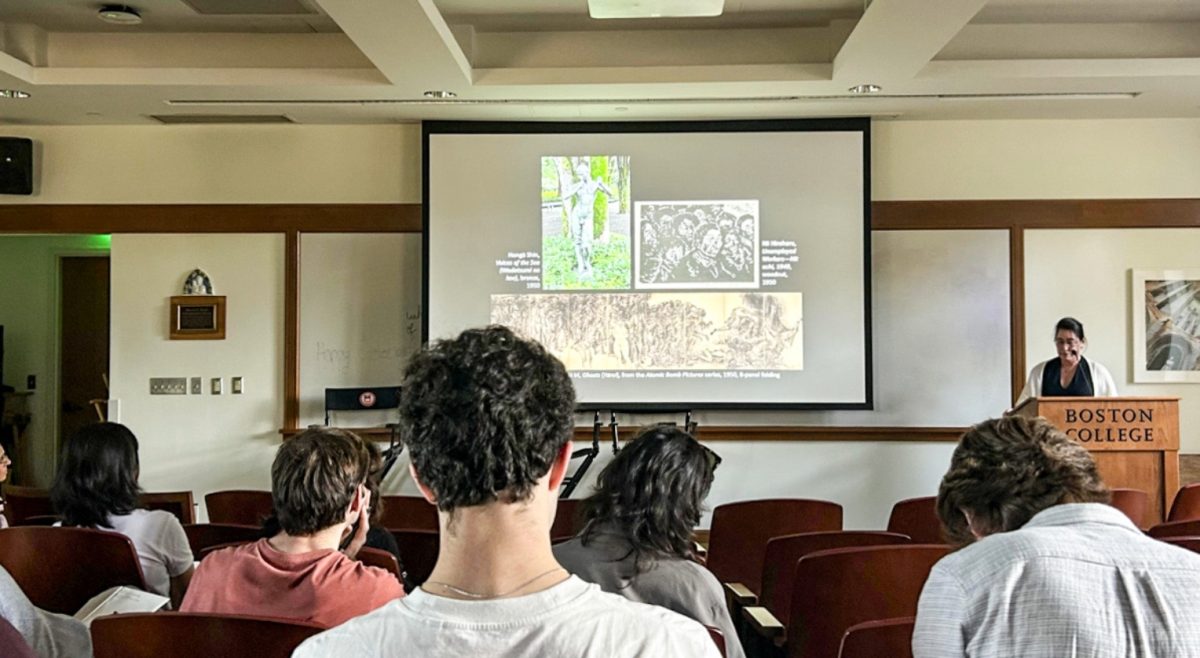

The exhibit displays a variety of his published poetry. His various works including their revisions make appearances, giving a broad representation of Yeats’ talent. The Tower (1928) highlights his maturing style. The Celtic Twilight (1893) chronicles an emerging Anglo-Irish tradition and A Portrait of Yeats, by his father John B. Yeats, brings context to his upbringing and influences.

An interesting aspect of this exhibit is the showcasing of several copies of the same work. Yeats was a fan and advocate of revision. When redacting, he hoped to more accurately convey his feelings, not adequately articulated during his younger years. In an attempt to bring a more holistic comprehension of individual pieces, Yeats sought not to alter the sentiment and feelings of his poems or stories, but bring them to their fullest potential. Suggesting that arts do not remain stagnant from their initial recording on paper, Yeats exercises a creative power, unfettered by convention.

Several poems, mounted on the wall of the exhibit, bring attention to two important overarching themes within Yeats’ craft. “The Rose Tree” (1916), “Coole Park, 1929” (1933) and an excerpt from chapter 14 of Per Amica Silencia Lunae, draw the eyes of viewers, who revel in the beauty of his words, and give insight into his broader, more universal feelings. “The Rose Tree” represents the bloody affair of the Easter Rebellion, brought down by England from “across the bitter sea”. The rose tree, representative of Irish freedom, is quenched of its thirst by the blood of the Irish people. The poem illustrates the pastoral influences of Irish folklore, as the rose tree demands such a sacrifice from the populace, fancifully calling to mind ideas of hungry fairies and frightful beasts lurking in the woods. Yet in this kind of tale, the repercussions seem far from fantasy, as real conflict knocked at the door of the Irish people.

Similar ideas concerning nature and lore are expressed in more extreme fashion in “Coole Park, 1929”. Yeats recalls the past with various references to influential Irish writers, interspersed with more imagery of rural landscapes dominated by the elements. Tied to the land, this seems to be the work that best exemplifies the admiration Yeats has for those who came before him, and how, in very real ways, the lay of the land is dictated by these men, artists, as much as it is by those from England.

W. B. Yeats spoke to ideas, not unfamiliar to the minds of the common people. And yet he engages his readers in such a way that one cannot help but revel in his expert prose. Whether bellowing from the aches of unrequited love, or welcoming the harbingers of a new era is his homeland. Yeats meets the challenges and changes in his life, with challenges and changes in himself and his writing. Such a dynamic man gave birth to such dynamic works, beckoning to the future with equal portions reverence and hope.

Featured Image by Julia Hoptkins / Heights Staff