On the streets of San Agustin, Cuba, old cars dot the sides of the worn road and people walk beside colorful Cold War-era housing plots. Murals span walls, as underbrush creeps along the perimeter of fences and crawls up posts. Emitting a vibrant personality from every corner, onlookers and artists attempt to grasp at the city’s essence. As some of those walking the streets see the camera, many smile and say hello. Others shout out “Camara!” excitedly, as it captures their image, at least for a moment. The respect, enthusiasm, and reverence given to artists in Cuba remains markedly different in the United States. In such a different culture and political system, people will adopt different roles and functions from those in American society, but one of the most stark and striking differences between the two cultures remains the figure of the artist in each.

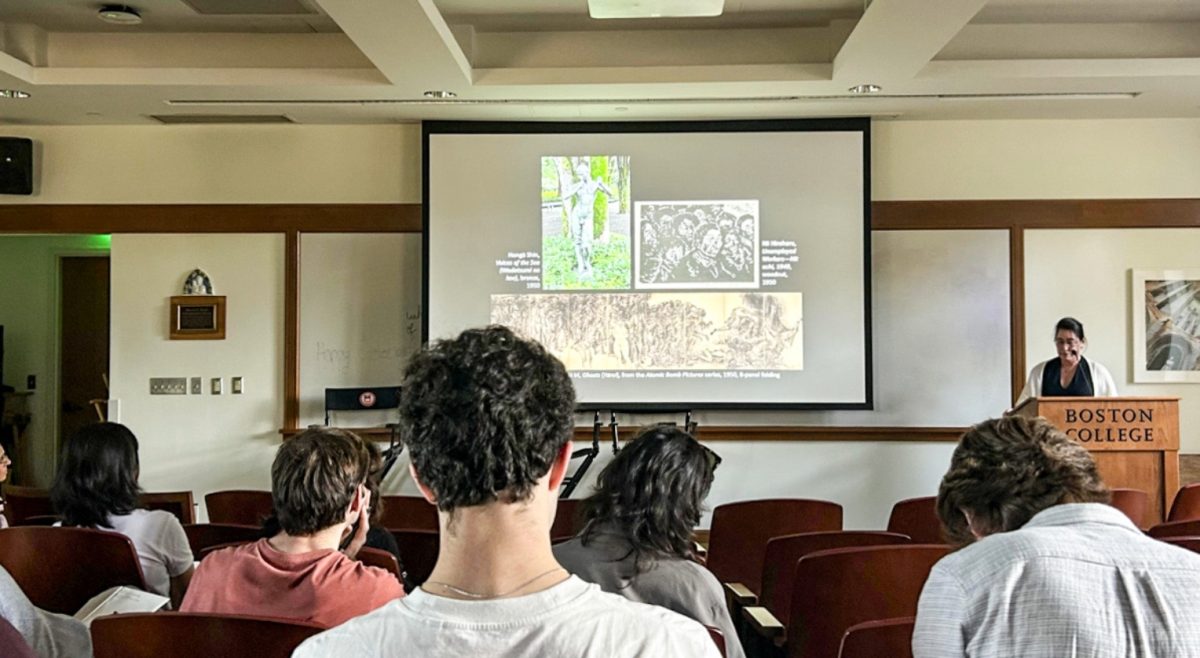

Emily Sadeghian, Adriana Sarro, and Oscar Rodriguez, all MCAS ’16, sought to flesh out such distinctions and differences in their documentary Laboratorio Artistico de San Agustin (LASA), funded by the Salmonowitz Grant. The LASA organization, founded by Cuban artist Candelario, exposes the people of San Agustin to contemporary art and various performance-art pieces, creating interesting dialogues in the community, as well as exploring art in action.

The trio hoped to paint a portrait of the artist’s role in the communist nation and how artists function within their distinct cultural framework. As relations between Cuba and the United States continue to thaw, onlookers may be challenged by these disparate views on art. The students’ journey and film show that there exist many ways to think about art and artists, both as observers and as integral parts of the artistic process.

Though one might believe that the biggest struggles for such a project might lie in Cuba itself, for the trio, getting to Cuba also proved to be an arduous and complicated process. Despite the lifts on travel bans, the group still had to cross through a lot of red tape to simply enter the country. It took around two months to confirm its air travel.

“We did not have our visas until a day before,” Sadeghian said, noting the visa process for entering the country remained difficult for U.S. citizens, even though the three held additional citizenships outside the U.S.

“We entered Cuba with a print-out of a picture of our visas,” Sarro added. Hardships like this added to the stress and uncertainty of the process. The group said a lot of trust had to be put in people it had never met, simply to secure its route to the country. The relative scarcity of Internet in Cuba made it difficult to confirm contacts and transfer crucial information like passports and credentials, they said.

“You have to enter Cuba in a mindset where you can’t compare,” Sarro said. “This is a new way of living, a new social order you have never experienced, so you can’t go in trying to compare what you have experienced to anything you have experienced before.”

The group flew from Boston to Texas to Mexico and into Cuba in a 24-hour process.

Upon its arrival, the differences between the two lands became ever more apparent, especially in regards to artists. While artists in the U.S. and other parts of the world may be relegated to positions of economic and social inferiority, in Cuba, artists live on a decidedly higher rung on the social ladder, they said.

“They see themselves performing a very high social role,” Rodriguez said. “They are very well-considered and regarded.”

The group encountered one artist for the documentary who recalled an exodus of artists from a Fidel Castro speech. When the former president made derogatory remarks regarding art and artists, artists defiantly stood up and left in an audacious fashion. That kind of exercise of power, in direct opposition to the president, is symbolic of the power dynamics at play within the community of artists in Cuba.

But the path to a career as an honored Cuban artist is not the sole choice of an individual. Factoring natural aptitude and academic success, only those fitting a certain profile in Cuba may choose to become artists. If one meets these prerequisites through tests, the door is open for interesting relationships with the government through subsidies on proposed projects through those who score high enough. The lifestyle of an artist is much different from other professions, leading to a higher sense of status, honor, and power.

LASA is able to subvert this process by managing both a business and artistic side, funding artists through means outside of the government. The organization’s founder Candelario employs non-artists with backgrounds in engineering, law, and philosophy, allowing for a wider swath of people to enter into communion with artistic ventures brought about by the business’ revenue. Additionally, the organization forges international relationships, inviting foreign artists to create anything from murals to fuel larger projects in the community. Cutting out the government as the middle man, LASA implements its performance-art pieces to build a rapport within the community of San Agustin.

Many, if not most of LASA’s projects involve the people of San Agustin as a portion of their performance piece. LASA works to illustrate the role of contemporary art, while exposing the populace to diverse ideas.

One set of performances, Los ensayos públicos (The Public Experiments), involved the five senses. The taste experiment had to do with rations. Each person in Cuba has access to one piece of bread a day. LASA remanufactured the bread with different ingredients to enhance the flavor and painted each a different color to signify these differences. At these ration stations, the people of San Agustin could then choose what kind of bread they would like, choice being a luxury in this context.

Another taste experiment created an edible map of San Agustin made of cake. The people were then asked to locate their house, after which they could eat it. The task proved difficult for many, however, because there are not formal directions or street signs in San Agustin. LASA designed these events to create a sensory experience for the people.

Though from the outside looking in, it would appear LASA’s aims may be to subvert the system in place in Cuba, but the intent is far less anarchical and revolutionary.

“The goal is to test people’s senses and make them see the world a little differently than the way they have experienced it their whole life,” Sarro said, describing how the San Agustinians’ world is structured in different ways. LASA, with pieces like this, looks to help people orient themselves in new ways.

In their documentary covering the influences of LASA, the trio entered Cuba with an open mind, not quite knowing what to expect. Over the course of the week, the group found that its own journey in Cuba became rather self-reflective, as it set out to create and discover, just as those in LASA sought to do the same in San Agustin.

“We are filming it and we are experiencing it,” Sadeghian said.

LASA does not champion itself as social workers in the community, but rather as artists who hone its craft in the context of its home, San Agustin. Using the people and its active participation in art, like another color on their palette, LASA uses this human element to make their aims all the more enthralling and captivating.

“What stood out the most, what is the most salient, is the idea of an organization that is ahead of its time,” Sadeghian said.

“The point of the art is not to inform the community,” Rodriguez added. “It is the art itself.”

Art, in all parts of the world, is placed throughout our lives to create context, bring light to issues, and challenge our beliefs. All kinds of art can ask countless questions, but no one artistic endeavor can truly answer all these questions and address all shortcomings. Organizations like LASA may bring some clarity to those questions, but also create more questions as they—as we all—begin to orient ourselves in the new ways the artistic works suggest.

Off the plane, Sadeghian, Sarro, and Rodriguez were told, “You are going to leave here more confused than you got here.”

“I think that’s completely true about going to Cuba, in a beautiful way,” Sarro said.

Featured Image by Emily Sadeghian / Heights Senior Staff