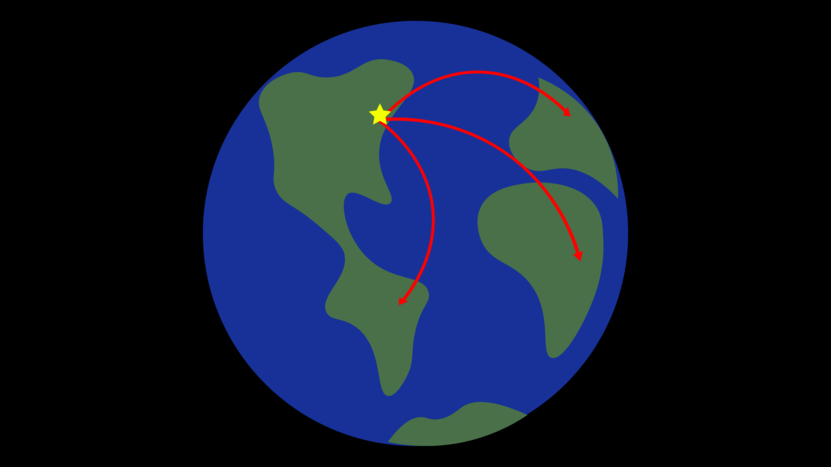

I wrote a column a few weeks back about the pressure that American students might feel to represent their country while studying abroad. I also wanted to take some time to explore how abroad students interface with their origin country while detached from it for extended periods of time.

Studying abroad is a commonly-discussed topic at Boston College. Freshman year, during floor meetings, at least one person comes in with the “and I definitely want to study in [insert country here]!”

Sophomore year the formal process begins, and those who have less conviction with respect to their destination, like myself at the time, go through all that the Office of International Programs has to offer to come up with a program that works.

Junior year is the culmination of all of this, where it feels that at any given point a decent percentage of your class is off gallivanting anywhere but the U.S.

And senior year, when returned students aren’t talking about their amazing cultural experience abroad, many love to complain about how much better [insert country name here]’s bars are than Boston’s.

I went abroad during the spring semester last year to Glasgow, Scotland. Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and has a long, rich history of industrialization, poverty, and religious and political tension. It also has some of the most breathtaking museums, a varied and unique culture, and a steadfast and defiant attitude that reflects all that the city has been through. The University of Glasgow, where I studied, is an incredibly liberal environment, and this is reflected in the neighborhood in which it is situated.

While abroad, I took a class on modern American politics taught by a professor that was born in Scotland but spent much of his life in America teaching. The class had a decently sized contingency of American students, and in his introduction to the class he explained that the Scottish half of the class would likely view him as American, and us Americans would see him as unequivocally Scottish. It was important that he prefaced the class with this information because it allowed us students to understand where he was coming from and frame his arguments.

Taking a class about my home country from the perspective of another culture, albeit a culture very similar to that of the U.S., proved to be an intense learning experience.

Our professor was unwilling to skip over the less than desirable aspects of American political history, and even less likely to sugar coat them. His approach was raw and informative and this helped to break down concepts that are often oversimplified. He also made a lot of comparisons between America and the United Kingdom, which were intended for the Scottish students to understand ideas more clearly. Because I did not have a full understanding of the United Kingdom’s cultural and political trends, I found these comparisons helpful in understanding my host country, an externality of his lesson.

That being said, I was also abroad for the inauguration of our current president, so the topic of the 2016 election came up frequently, especially around the end of January. Most Glaswegians I encountered unabashedly voiced their opinions of what they viewed as the dissolution of American politics.

The conversations I had forced me to look at America from a foreign perspective, and to try to understand how others view the U.S. I appreciated the willingness of most of the Scottish people I met to be very honest and clear with their stances, even before asking mine. This might not happen in many other circumstances, where often people try to feel out the other person before sharing their opinions. This approach to discourse was refreshing, and gave me more breadth and depth of my understanding of America than I ever thought I could have.

Most Scottish people were focused, unsurprisingly, on how the changing political scene in America would affect their country and their politics. Having left before the inauguration, I had never set foot in the U.S. under President Donald Trump until I returned home in May. Therefore, I had limited insight on current events in the U.S. I spent most of these conversations listening to people and framing their opinions with what I had learned from my class and from my American upbringing.

Studying the American political system from an outside perspective and having these conversations during my time abroad provided me with a different experience than studying in the U.S. I feel that stepping back and adjusting my lens of understanding enriched my comprehension of America.

While it is vital for American students abroad to consider how they are representing their own country, I also found that studying abroad allowed me to step back and see how my country represents itself.

Upwards of forty percent of undergraduate students at BC have an international experience during their time at the University, whether it be a full year, a semester abroad, or other shorter programs. Those who are lucky enough to go abroad will inevitably learn about their host culture, but should be cognizant of the opportunity to learn about their own culture from an outside perspective as well.

Featured Image by Zoe Fanning / Heights Editor