For Rev. Oliver P. Rafferty, S.J., coming to terms with his role in life didn’t take very long. Named after the Archbishop Oliver Plunkett, he assumed his position in the religious order with the confidence and surety only a child can have.

When his headmaster asked him on his very first day of school what his name was, Rafferty had an answer.

“I pulled myself up to my full height and declared ‘Blessed Oliver Plunkett Rafferty.’”

Born in Belfast, Northern Ireland in 1956, Rafferty grew up in a predominantly Catholic community in the throes of protest and discontent between religious groups. As children, he and his three brothers and four sisters were told by local Protestants that they would never be able to get jobs due to their family’s Catholic faith. A teenager growing up during the Troubles, a time when the Catholic minority wished to be a part of the Republic of Ireland while the Protestant majority wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom, Rafferty saw the conflict in all its power. Several people in his year at school were killed during the Troubles, and one even starved himself to death during the IRA hunger strike of 1981.

“The violence of these issues touched me personally,” Rafferty said.

Despite the violence and unrest related to religion that he witnessed during his formative years, Rafferty never doubted what he wanted to do as an adult. When asked what he envisioned himself growing up to be when he was a young child, he didn’t even take a breath before responding.

“A priest.”

As Catholic families typically had many children, it wasn’t uncommon for one of them to join a religious order. Nowadays, as people have smaller families, the number of young people looking to join is dwindling.

“To have priests and nuns in the family was to be regarded as a mark of esteem,” Rafferty said of the past. “There’s been a shift in the culture.”

During his time as a professor, he’s only come across one student that he knew was interested in becoming a priest, but not a Jesuit. While he doesn’t think that it’s necessarily a concern among the Jesuit community, he does say that it is becoming difficult to fully staff the 28 Jesuit colleges in the United States.

His greater concern with education lies not within who is teaching, but in how students are learning. Rafferty went to England for three years to study at Heythrop College at the University of London—a school run by Jesuits. His workload consisted of one paper per week, which didn’t count for a grade—it only served to develop his skills and increase his knowledge of the subjects he studied. His only formal exams were at the end of his three-year university career.

“It’s probably more difficult for people in the American system to cultivate a love for their subject,” he said.

Rafferty went to college with the goal of learning what he believed was important, and he picked the school that reflected his ideas on that. When he went to Heythrop, he studied the only two majors offered: theology and philosophy.

“I tended to be a shy person,” he said. “I read somewhere that a good means of overcoming this would be to study philosophy.”

Despite his hope that philosophy would “broaden his mind and take him out of himself,” Rafferty found that he didn’t quite take to the subject. He favored theology—after three years, he joined the Jesuit order. Because of his college degree, Rafferty was ordained within eight years of joining.

As an academic, he most wanted to teach at the elementary level. He had very specific ideas of what and how children should be taught—he had visions of himself teaching Greek and Latin to 7-year-olds—but he was appointed as the head tutor at Oxford University. After beginning his career in the academic sector, Rafferty decided he wanted a change of pace for his first sabbatical.

“I thought, I will not have any other opportunity in my life to function as a priest,” Rafferty explained.

What was supposed to last one year ended up taking three—his contact person in Guyana, the South American country that he decided to do pastoral work in—convinced him that the extra time in the interior of the country would allow him to better connect to the indigenous people that he was living and talking with.

The work was isolating. Guyana is roughly the size of England and had only 50 villages. Rafferty spent only a week in each village before packing his bags, saying goodbye, and traveling on his own to the next location. Even if his visits hadn’t been so short, there was still one other thing in his way: the language barrier.

Rafferty joked that the old ladies in the village didn’t mind that he couldn’t understand them—they were just happy that they were giving confession to someone who couldn’t understand their sins.

“Those who had English, and that was true of many of them, I made them say their confessions in English,” Rafferty said with a laugh.

Although he had wanted to escape the world of academia for a short while, Rafferty did stay connected to the professional world while abroad by editing several books. And when it was time for him to return to his career, he persuaded his provincial that North America would be the best place for him. After a one-year teaching stint at the College of the Holy Cross, however, Rafferty returned to Heythrop for five years.

Coming back to his work, Rafferty was different than he was before his sabbatical, if only in the sense that he knew what kind of academic he wanted to be.

“That gives you a different view of yourself,” he said. “A different view of the life, a different view of what you’re doing as a teacher and researcher and writer.”

He knew that he wanted to explore teaching Irish history, since he had only done religious history before. When University President Rev. William P. Leahy, S.J., found out that Rafferty was potentially on the market, he invited him to visit Boston College. After giving a lecture, Rafferty said he was invited out to dinner.

“They took me out to dinner to see that I had proper manners whilst eating,” Rafferty said.

When Rafferty was offered a position to teach, he accepted—BC boasts a collection of books on Irish history and literature that Rafferty says could compete with a library in Ireland. He thought it would be the perfect fit. He quickly realized the way BC students operate after he only had six students in his first class—one must never sign up for class with a professor that doesn’t have a rating on PEPS yet. During his second year, a coworker was unable to teach a class and Rafferty was able to step in, earning his reputation and forging new relationships with students. He found that American universities require something of students and professors that isn’t as prevalent elsewhere: friendliness. He has certainly been successful in achieving a high level of respect and admiration among his students.

“He’s just a really genuine guy,” said James Wills-Singley, MCAS ’19, who had Rafferty for a sophomore history class last spring. “He’s a historian, but what attracted me to all his classes is just him telling these stories that are funny and entertaining.”

Being a priest, a figure that people often have high expectations for, Rafferty is conscious of the way students perceive him. The Jesuit professors at BC are asked to wear their traditional religious garb while teaching. Rafferty says that it serves as an extra reminder of the way he should act toward his students—he makes sure to always be open to his students by being kindly disposed.

“As a teacher and a professor he loves to make people laugh,” Singley said. “He’s lecturing for an hour and within that hour he’s telling these hilarious stories about these important figures that kind of bring levity.”

Even though Rafferty loves the time he gets to spend with his students, sometimes cooking dinner for them in the kitchen of another Jesuit’s house on campus, there’s one thing that really makes him feel that he’s in his element.

“Being on my own and reading books.”

Rafferty has published seven books himself. His most recent—Religion, Politics, and Violence in Ireland—explores the topics that he first became interested in back in his teen years during the Troubles. He’s currently working on three articles—one was supposed to be due the day after we spoke. Rafferty sort of laughed when he told me the deadline, and then said that he didn’t anticipate finishing for another week.

As for his future works, Rafferty would love to write a detailed account of Christianity in Ireland from inception to current day—a large feat that he has casually begun to collect information for, but hasn’t formally started researching or writing. He’s currently working on a book about the relationship between church and state in Ireland that he hopes to finish by the end of his next sabbatical, which begins in about three years time. Where he’ll be in three years, however, is unknown.

“I have a visa that Mr. Trump decides he doesn’t like,” he said with a dry sort of laugh.

When Rafferty’s visa expires in November of this year, it’s possible that he will be required to return to England or Ireland. He’s currently working, with the help of the University, to get it extended for three more years or apply for a green card. Although he is slightly anxious about being forced to leave, he recognizes that his work can take him anywhere.

“I will never be out of a job as a priest,” Rafferty said. “If I have to go back across the pond, I’ll find things to do there.”

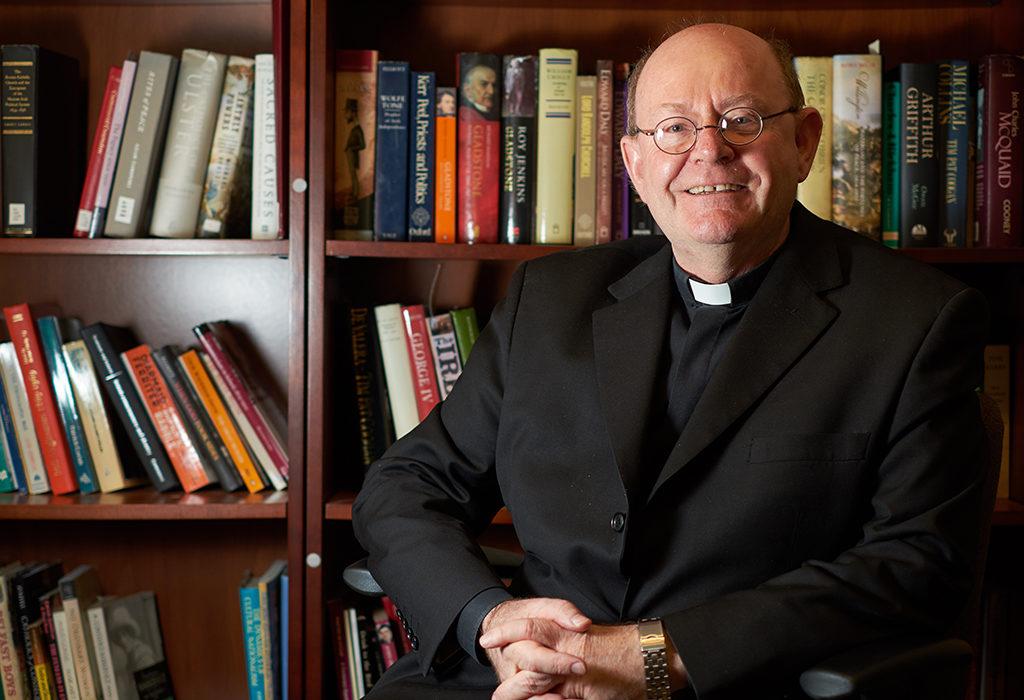

Featured Image by Sam Zhai / Heights Staff