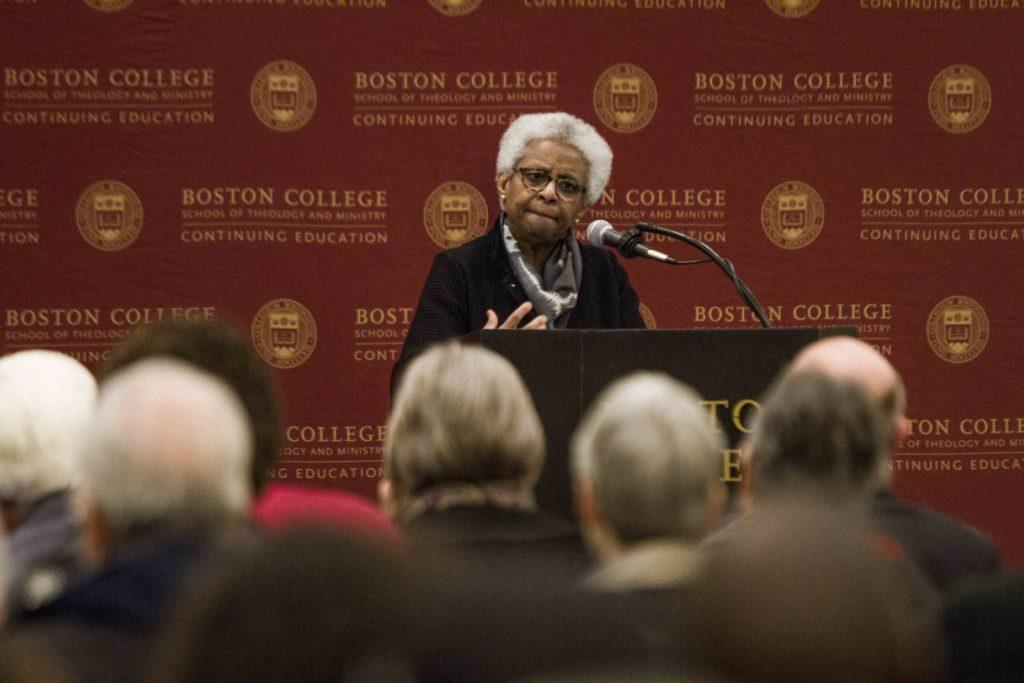

M. Shawn Copeland, a professor in the theology department, the African and African Diaspora Studies program, and in the School of Theology and Ministry, lectured on the prophetic political theology of Martin Luther King, Jr. in the Heights Room on Wednesday, the 50th anniversary of the civil rights leader’s assassination on April 4, 1968. Copeland used the words of King to highlight modern day struggles surrounding race, poverty, and war, and the deep social changes that are necessary to bring about a better society.

The lecture was sponsored by the School of Theology and Ministry, as well as the Boisi Center for Religion and American Public Life and the theology department.

Copeland began the lecture with a discussion of King and his role in society.

“Throughout the nearly 13 years of his public, Christian social ministry, King so attuned himself to the word of God, as to recover and to exercise the biblical vocation of prophecy for his country, our country, indeed, for the world.” Copeland said. “Like the prophets of old, he was a watchmen, scrutinizing the signs of the times in order to witness to and to speak God’s justice and providence in an oppressive and anguished world.”

King’s deep-rooted Christianity and vocation as a minister established his belief in the equality of all human beings as made in the image and likeness of God. From this belief, Copeland said, came his struggle to end racism and poverty.

“King raised his voice to denounce injustice and put his body on the line in disciplined, non-violent civil disobedience,” Copeland said. “He responded to the demand of conscience to proclaim a new social vision grounded in faith in God to uphold the goodness of all humanity, and to affirm the spiritual, cultural, and social potential of the United States.”

Copeland discussed racism and what people can learn from King about its present form in society. Too often, Copeland said, racism is thought of as a series of isolated acts committed by specific individuals rather than contained in public institutions that mirror the beliefs, values, and judgements of society as a whole.

“Such structures sinfully impeded the very existence, the life, and flourishing of others simply because they are Native American, or African, or Asian, or Mexican, or Latinx, or of mixed racial-ethnic descent,” Copeland said.

She stressed that racism is a learned behavior and set of beliefs that is often unconscious in the minds of many Americans. It has roots stretching back so far that it is rarely acknowledged or questioned by society, and manifests itself in the media, in social institutions, and markets. She said that King challenged the prevailing idea of freedom and democracy as the main characteristics of the United States when it had acted opposite those values in many cases. King also challenged religious institutions in the country as complacent in this racism at cost of their moral authority.

Moving on from racism, Copeland defined poverty as the inability to attain basic human needs, and noted King’s opposition to the poverty of any race, quoting his work, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

“The curse of poverty has no justification in our age,” King wrote. “The time has come for us to civilize ourselves by the total, direct and immediate abolition of poverty.”

King criticized the programs in his own time that failed to actually alleviate property, and supported either full employment or the creation of a guaranteed income set at the median national income. He saw the elimination of poverty as something that could benefit and unite all minorities and whites, and wished for an economic system that focused on the person rather than on profit and property.

From poverty, Copeland moved to King’s push for peace in the then ongoing war in Vietnam, motivated by his Christian belief in the brotherhood of all humanity regardless of ideology and that garnered him criticism from many segments of American society. King criticized the sinful spending billions on the military when there existed so many people in poverty. King was also concerned by young African American men going abroad to fight and die for freedom and democracy that they could not enjoy in their own country.

“We here tonight would do well to remember that in the 1960s, in many Northern cities, these same black and white men could not live in the same neighborhood,” Copeland said. “Nor could young black men wearing the uniform of the United States Marine Corps feel safe from physical assault in white Southern towns.”

Based on the writings and actions of King, Copeland called for serious examination of racism, a greater understanding of the human person, a commitment by the church and its members to preach a social gospel, a transformation rather integration of society and values, a greater emphasis on hope.

Copeland finished with a discussion of King’s place in society’s conscience. To her, he has been placed on a pedestal as a saint and prophet of conciliation that all are comfortable with remembering.

“There is another King, one I hope I have shared with you this evening, the one we too conveniently overlook,” Copeland said. “The King who makes us uncomfortable. This is the King who condemned the Vietnam War, the King who sadly indicted his country as quote ‘The greatest purveyor of violence in the world.’ The King who charged that quote, ‘The life and destiny of Latin America are in the hands of United States’ corporations … This is the King who does not offer us an easy conscience.”

Featured Image by Kaitlin Meeks / Photo Editor