Patrick Maney thought he would cure the sick, not catalyze the Kennedy conspiracy theory.

Back in 1992, George H. W. Bush signed the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act, restricting access for 25 years to to documents surrounding the assassination. These documents centered around the CIA and FBI having possible knowledge of Lee Harvey Oswald in Cuba months before the assassination.

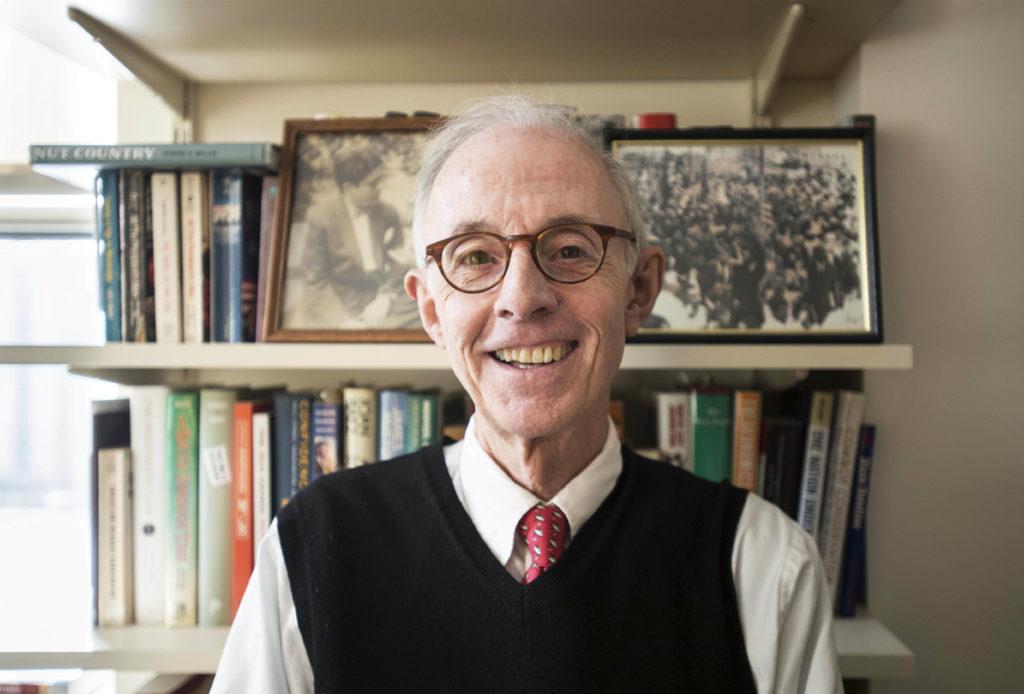

Twenty-five years later, with information soon to be released, the Associated Press came to talk Boston College history professor Maney about the documents. “I gave her an innocuous quote, with something like ‘One of the problems with keeping all of this stuff secret for such a long time, it fuels these conspiracy theories,’” Maney said.

The quote from the article, however, reads: “As long as the government is withholding documents like these, it’s going to fuel suspicion that there is a smoking gun out there about the Kennedy assassination.” What a smoking gun it became.

The story spread like a bad flu. Two days after the article was published, Maney had over 100 requests for interviews from publications like BBC and CBC, as well as publications in Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia.

Maney ended up doing about 30 interviews, only for local publications. His newfound fame didn’t really change much about how he spoke to the press. He believed, and still believes, that there are people who are more expert on the subject—who are more versed in the details of the situation—who would be better subjects for the larger publications. Never one to do an interview just to be quoted, if Maney doesn’t know enough about a subject, he’ll decline to talk.

After looking over the documents, he concluded there “really were no bombshells” and that the information that was released didn’t tell the world anything it didn’t already know. In his mind, the articles should never have been kept secret, as it caused more commotion than any of the articles could back up. All it did was embarrass the CIA and FBI to a small extent—and it’s not as if this discomposure has never happened before within American history.

But, growing up, Maney never envisioned causing this much conflict in the American narrative.

From a young age, Maney found himself inside the walls of hospitals. He started on a surgical floor in a small town branch of Wisconsin State University, where he earned a degree before the 1971 University of Wisconsin and Wisconsin State University merger.

“I loved working in a hospital. I enjoyed doing stuff for people, and I just thought it was really neat,” Maney said.

Asking him where he’s from is a difficult question, having attended four different high schools, in addition to a number of grade schools. His father worked for an insurance company and throughout the years was transferred to parts of Wisconsin and the Kansas City area, flipping between the two. He finally had the ability to stay in one place when he attended college close to home, graduating in 1969.

It wasn’t always easy moving from place to place so often. Coming to a new system every year did eventually leave its mark, with somethings being left behind in the process, both socially and academically.

“It was really hard and not real pleasant,” Maney said. “When I was in grade school, one school I went to had not gotten to long division or decimals. The next school I went to already had it, so I never learned how to do long division, and this was decades before electronic calculators, so you just had to know that.”

All this being said, he puts a positive spin on this part of his life. He attributes his ability to adapt and his desire to seek new challenges to his constant moving around. He values the stability that comes from staying in one place, however, and he credits his wife for opening him up to the rewards of a life less traveled.

At this point, he’s written three books—his most recent one about former president Bill Clinton released in January of 2016, worked in the Wisconsin State Senate, served as head of the history department at Tulane University and the University of South Carolina, and Dean of BC’s Morrissey College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, where he now teaches. He considers himself lucky to be able to teach classes such as Study & Writing of History: Clinton Presidency and the United States, 1929-1960 as he would be doing this kind of work regardless as a hobby.

As a history professor, Maney loves to examine every angle. He offers no single answer on any subject. He forces you to think outside of the small scope that many kids are used to in their AP U.S. History class, or in his case, from whatever material the high school coach turned history teacher could muster up for a lesson. That all changed when he went to college and took some of the history classes his freshman year. Maney recalls how “they forced me to rethink all of the assumptions that I had, and that’s what I try to tell my students. In college, it’s time for you to rethink these things.”

This idea of a full spectrum even touches back to his days in the hospital. As much as he loved medicine, he thought that he needed a more open subject, rather than the already known, and forcibly memorized, information that comes standard within the medical world.

“If you come out of college the same as you went it, it’s a missed experience,” Maney said.

With that, he decided to attend graduate school at the University of Maryland in order to seriously pursue history. “I tell my students, ‘Why did I want to go into history?’ Because I’m interested in it. Will history save the world? I doubt it. Will it save my life? No, but I’m interested in it anyways.”

Maney enjoyed the things and people he studied at Maryland, especially the life of Robert M. La Follette, Jr. (he finished his studies by publishing Young Bob: A Biography of Robert M. La Follette, Jr in 1978). When Maney emerged from academia, he struggled to find a job within the humanities sector, which sounds all too familiar to humanities students even now.

Luckily, he was able to begin working within the Wisconsin State Senate, under the wing of Clifford W. “Tiny” Krueger, a former circus actor turned politician. Tiny had an uncanny ability to predict the outcome of political standoffs, and was able to bring a measure of personality to politics. Maney credits the way he sees the political world today in part to him. He learned about politics in a way no one can learn studying it through Krueger.

He credits Krueger as being one of the most influential people in his young life. The work experience was invaluable, arguably the most important of his career. As a political historian, he learned more about politics by being involved in it than he had reading any book or during his seven years of graduate school.

As a minority leader, Maney was exposed to another side of politics, and was truly invested in who he was serving. In times where senators on the Wisconsin state senate would criticize it and say “this is like a circus,” he would say that was disparaging to the circus.

“I loved it … I’ve seen more of what people imagine is politics, like maneuvering and backstabbing and all the rest of that,” Maney said.

But, after three years working under Krueger, it was time to move on, and his next stop was Tulane, then South Carolina. “I never thought I would ever end up in the deep south,” Maney said.

Finally, he made it above the Mason Dixon line, and landed at BC. He began his tenure as the head dean of the Morrissey College of Arts & Sciences, but, after two years at the helm and given his life status as a nomad, change was inevitable.

Maney then gravitated back to an old habit: teaching. His place was in the classroom, helping students see the world in a way that hadn’t before, not doing administrative work. He created a dedicated network of undergraduate researcher for his book on President Clinton.

“The experience was the perfect combination of working, learning and enjoying genuine conversation with Professor Maney,” said Giancarlo Ambrogio, BC ’16. Similarly, Greg Manne, BC ’12, remarked, “I was an aspiring history teacher with a keen focus and interest on modern U.S. history, so to participate in this … with a renowned professional was really incredible.”

Although famous with the BC community, he became a new network, and cult theory, celebrity overnight in regards to a recent JFK assassination case in October 2017.

Each generation has a specific moment in its history that marks that time: Pearl Harbor for the Greatest Generation, Sept. 11 for Millennials, and the assassination of Osama Bin Laden for Generation Z. For the Baby Boomers, it was the assassination of JFK. John F. Kennedy captivated the nation by becoming one of the first presidents with celebrity status.

Maney recalls the power of JFK as “my first political hero.” He talked about, as an eighth-grader, waiting to meet the campaigning Kennedy at the airport in October of 1960. He recalls being the only kid there, but having his coveted handshake hijacked by a woman wearing a Nixon pin as Kennedy reached right over his head for her hand. “I’m thinking, ‘that’s the day I almost got to shake the hand of Kennedy,’” he said.

Featured Image by Kaitlin Meeks / Photo Editor