When the U.S. Embassy in Kuwait apologized to Boston College political science professor Kathleen Bailey for not being able to host her and her students for the second year in a row, she took it with a grain of salt.

“We were even too busy,” she said. “They put on a program that’s five hours, and we didn’t have five hours.”

The one-credit course, Kuwait: Intercultural Dialogue and Diplomacy, culminates in a weeklong trip to Kuwait—this year, the trip took place from March 2 to 11. Unlike many BC classes offering singular credits, this highly selective program offers a unique opportunity for immersion. At the helm is Bailey, an expert in the Muslim regions and the associate director of the Islamic Civilization and Societies Program at BC.

The trip is made possible by The Omar A. Aggad Travel and Research Fellowship, which provides grants through donations made by a BC family to be used for the purpose of catalyzing connections with the Middle East. In addition to hosting speakers at BC and funding the research projects of individual students, the fellowship covers much of the costs for the 10 students enrolled in Intercultural Dialogue and Diplomacy to spend their Spring Breaks on Kuwaiti soil.

“The Aggad family gave the gift with no particular insistence that it should be used for this or that or anything, but … [Aggad] really liked the idea of face-to-face diplomacy and dialogue,” Bailey said. “But no matter what it was, he wanted the students to be meeting counterparts, rather than being lectured to all the time—some kind of meeting of the minds.”

The Spring Break trip was Bailey’s creation—by condensing a study-abroad experience into a weeklong excursion, she combined immersion with accessibility, giving her students the unique opportunity to act as participants in Kuwaiti culture, rather than as stereotypical tourists. Aiming for an all-encompassing excursion, Bailey organized activities under several different categories, from the development of Kuwait’s economy to the politics of its government.

As with the agenda, Bailey selects her students with care. She reads every application herself, and while high grades and a thoughtful essay are considered, Bailey makes sure to look beyond rank and rhetoric.

“One thing that’s a little bit unusual is [that] I want people who are engaged, so people who are really excited and very open, and good conversationalists,” she said.

To prepare for the journey, Bailey uploads readings and articles—a hodgepodge of historical, political, and economic documents—to Canvas. The students are responsible for preparing the material in advance of class discussions.

These conversations establish a necessary baseline to give students the knowledge they need to be active participants in Kuwaiti culture.

“Kuwait is a place where you really could get some cultural dissonance,” said Bailey. “You might feel alien, displaced almost, like a fish out of water.”

Kuwait is starkly divided into two sociocultural groups, the first of which has existed since the state’s creation. In the mid-18th century, tribes emerged from modern-day Saudi Arabia and developed Kuwait as it exists today. Before the age of oil, the early Kuwaitis were pearl divers, utilizing their proximity to the Arabian Gulf. They were traders, merchants, and shipbuilders, forced to find other ways to survive in the inarable desert—the cobalt coast morphed into their Mesopotamia.

Today, these early pilgrims are Kuwait’s merchant elite, and comprise roughly 35 percent of the population. The other group originated as nomadic herders who remained in the comfort of the desert—they didn’t participate in travel, education, and weren’t integrated into Kuwait’s governmental system until the mid-1960s.

Between the merchant elite and the nomadic population, members of the former group tend to be wealthier, more globalized, and more contemporary than the contrasting tribal nomads—ancient, conservative customs such as polygamy, gender segregation, and nomadism are the norm.

Nowhere is this cultural cacophony more visible than in the country’s universities, two of which—Kuwait University and the American University of Kuwait (AUK)—Bailey and her students visited.

AUK is a liberal, private institution with English as the language of instruction. Due to the university’s partnership with Dartmouth, the curriculum is taught in the American style. “When you walk around AUK, you’re not in an American university, but it’s something that you can kind of understand and grasp, and there are common experiences,” Bailey said. Generally, children of the ruling, merchant elite are sent to this institution.

In contrast, Kuwait University tends to be frequented by members of the tribal population. As a state-sponsored university, tuition is not only free, but students are compensated on a monthly basis by the government for their attendance—approximately 2,500 Kuwaiti dinars, or $3.20. Students are also compensated for textbooks, scholastic materials, and study abroad trips.

The Arabic language of instruction, as well as the nonexistent cost and conservative culture on campus, appeal to many in this second sociocultural group.

“On the two different campuses we saw two very different crowds. The AUK students … are the most liberal students. I talked to a Kuwaiti Muslim girl with blue hair, tattoos on her shoulders, and like 10 ear piercings,” said trip-goer Echo Yiyang Zhuge, MCAS ’20, who took Bailey’s Inside the Kingdom: Conversations with Saudi Women course as a freshman and heard about the Kuwait trip when she was working in Qatar last summer. “I asked her: ‘You’re Muslim, are you allowed to have tattoos?’ and she just shrugged. That’s the kind of student we saw on the AUK campus.”

The colorful, cropped clothing worn by most students at AUK reminded Zhuge of the apparel donned by students at BC, but at Kuwait University, every woman on campus wore a traditional hijab, as well as a niqab—a veil to cover the face.

“When we picture a gulf country or an Arab country, we usually think of women in black bundles,” she said. “But in Kuwait, we saw two extremes. Kuwait University honestly is the norm. AUK is what a very small minority would act like … the point is that they exist.”

Contrarily, the conversations BC students had with students from Kuwait University were all with men, who described their participation in polygamy and the self-segregation of genders in the classroom—women sit in one corner, and men in the other. This cultural chasm was much more narrow at AUK, where BC students were shown a music room where students of both genders crooned melodies and struck chords as they played what Bailey compared to Rock Band or Guitar Hero. One BC student on the trip recognized the lyrics to a song the AUK students sang, and joined in.

To Bailey, this represents a unique element of progressivism AUK holds paramount.

“I doubt you could even play music at Kuwait University,” she said. “Music is not something that in the Muslim faith is really acceptable. So AUK defies that, KU stays with the more traditional interpretation.”

In addition to their planned group activities, the BC students were given opportunities to explore the state and engage with the culture surrounding them. One afternoon, Zhuge dragged her friend Matthew Hekmat Aboukhater, MCAS ’20, on an outing to a pre-Islamic art museum she had on her bucket list. Next to the museum, they saw the only Christian churches in all of Kuwait.

The two buildings—one an Evangelical church and the other a Catholic church—were filled exclusively with expats working in Kuwait, who had come from countries such as India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. As a monotheistic religion, Christianity is one of the only religions besides Islam tolerated to an extent by the Kuwaiti government—Buddhist and Hindu temples, for example, are nowhere to be found.

This tolerance, however, does not amount to acceptance. Visiting a little shop appended to the side of the church, Aboukhater was shocked to discover the sale of contraband keepsakes. Pulling a pinky-sized object out of his pocket, Aboukater proudly presented a canary-yellow eraser, shaped like a cross and printed with the words, ‘Jesus Saves.’

“I bought something that’s illegal to buy,” he grinned. “In Kuwait, you’re not allowed to own a Christian cross, but I bought this. A Christian, tiny cross that was sold, and the only way it was sold is because it’s a literal eraser. I bought that, and we hid it, and we transported it back to the United States.”

In addition to visiting the only two churches in the country, Zhuge and Aboukhater accompanied the rest of the group on a tour of the Grand Mosque of Kuwait. Normally, non-Muslims are prohibited from entering mosques, so the non-Muslim students embraced the opportunity to admire the towering central dome, hand-carved gypsum, and glittering chandeliers—each weighing about the same as a car.

“I’ve never been inside a mosque,” Zhuge said. “It is important for me because I study Islamic art, and I’ve only been able to look at mosques from the outside.”

Expanding on this unique opportunity, Zhuge noted Kuwait’s progressiveness relative to other gulf countries.

“I actually saw a lot more diversity in Kuwait than [when] I worked in Qatar over the summer,” she said. Just a short 40-minute flight from Kuwait, Qatar’s conservatism reaches beyond religion. “I really felt like I’m much more free to live as a woman in Kuwait than I was in Qatar.”

Zhuge also came to realize this sentiment when the group attended a diwaniya. Traditional in Kuwait, diwaniyas are nighttime gatherings where friends and neighbors gather for an evening of delicious food and stimulating conversation. These parties are held in rectangular rooms with couches lining the perimeter. The middle is left empty—an homage to Kuwait’s nomadic culture.

“Everybody can let [their] hair down,” Bailey said. “You can have fun, and just talk, and talk about anything.”

One stipulation is that the guest list is strictly male, but for Bailey’s students, an exception was made. “My experience was completely different than Echo’s because I’m a guy,” Aboukhater said.

Bailey’s long-standing connections with the Kuwaitis didn’t decrease the novelty, however.

“When [the female students] told other Kuwaitis they were going to a diwaniya, they were always shocked, because it’s not a normal thing to do,” Bailey said.

Although Kuwait is a monarchy, it is a country constantly trying to grow and welcome new ideas. Bailey took her students to sit in on a session of Kuwaiti parliament so they could understand not only the politics of the parliament, but the government as a whole.

The Kuwaiti parliament is comprised of 50 ministers of parliament, or MPs. Kuwait’s oscillations between absolutist monarchy and parliamentary democracy are apparent in the makeup of MPs. While the majority of them are elected by the people, 15 ministers are chosen by the emir—the ruler of Kuwait, currently Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah—who also has veto power over any of the resolutions passed by the ministers.

During the session they attended, the students witnessed a heated ‘grilling session,’ in which one of the ministers was harshly interrogated. This was followed by a vote on whether or not the minister should resign.

“A lot of what’s going on in Kuwait is just … political games being played from both sides,” Aboukhater said.

The students watched as he defended himself against the accusations, and the next morning, they opened the newspaper to read that the emir had made an appearance himself to praise the minister on his self-defense. Ultimately, the man was allowed to keep his job, and the accusers were criticized by the press.

“For me it shows that there is a rigorous democratic debate going on in the government, Zhuge said. “Is it struggling? Sure … but I think a lack of struggling would be a much bigger problem. The strife the students witnessed stems from a motivation to hold the ministers accountable for their actions, which the Kuwaiti newspapers can report on, condemning government authorities if necessary.

“I saw a country trying to progress, trying to democratize itself … they’re doing their best to balance between a chaos led by the tyranny of the majority of authoritarianism,” she continued. “It’s a very tricky and delicate balance.”

Kuwait has expanded this dedication to development to the area of foreign affairs. As a textbook example of diplomacy, Kuwait has never initiated a war or conflict, and remains neutral in major international conflicts—even in the Arabic world. From the Syrian Civil War to the Libyan Instability Crisis, Kuwait has embodied the highest standard of statesmanship.

A lot of times, Kuwait’s chivalry stems from circumstance, rather than choice.

“Kuwait is a very small country. It’s not easy to protect, so security is an issue. … Kuwait has to be friends with everybody,” Bailey said.

It’s fitting that the first stop the students made was to visit the Kuwait Diplomatic Institute, where Kuwaiti diplomats are trained. Rather than instructing future diplomats in various centers or graduate schools which include competitive application processes, all of them are trained by the director general for Kuwait Direct Investment Promotion Authority, Sheikh Meshaal Jaber Al Ahmad Al Sabah, along with his staff of professors and practitioners.

Because the American embassy wasn’t on this year’s itinerary, Bailey called on an old friend she attended the Fletcher School with, Tshering Gyaltshen Penjor, the ambassador to Kuwait from Bhutan. As a small, democratizing monarchy, Bhutan is similar to Kuwait in structure and provided an enlightening opportunity for the students, who conversed with Penjor regarding how Bhutan maintains its diplomatic relations in another difficult part of the world.

Kuwait’s diplomacy is strategic in the sense that its small dimensions and lucrative oil production make it easy and tempting bait for its larger, neighboring countries. Hoping to enlighten her students regarding Kuwait’s economic development, Bailey took them to the Kuwait Oil Company.

With the extensive background knowledge provided by Bailey’s assigned readings and course discussions, the students were able to think critically about the future implications of Kuwait’s large reliance on a finite, and limited, resource.

“I think Kuwait’s great right now, but they don’t really have a plan for the future … for renovating their economy post-oil,” Aboukhater said. “When we asked [the tour guides] about potential other economic endeavors, they really had no answers for us. All they talked about was how many barrels of oil they were producing.”

Given the freedom to construct her own itinerary, Bailey was determined to balance traditional activities with a few unique, exciting opportunities for students to immerse themselves in Kuwaiti culture in less formal settings.

“It’s an intense trip because we do an awful lot, I mean those first few days, they were so filled,” said Bailey. “I think we had maybe four or five activities … you need to mix that with more, well, fun things, so that you’re not always on the edge of your seat.”

To achieve this aim, Bailey took the students to a private beach chalet, an underground hip-hop class, and a treasure hunt searching for goods in a traditional Kuwaiti marketplace known as a souq. She insists that these activities are essential to the immersive experience the trip provides, as it encourages participation in Kuwaiti society, rather than being detached in formal, classroom settings.

“I think [these activities tell] you a lot about other people, and it really brings out the commonalities,” Bailey said. “The people are concerned about the same things. You come halfway across the world to a completely different culture … you’re not in Europe, and yet, you could be talking to your sister and have the same conversation.”

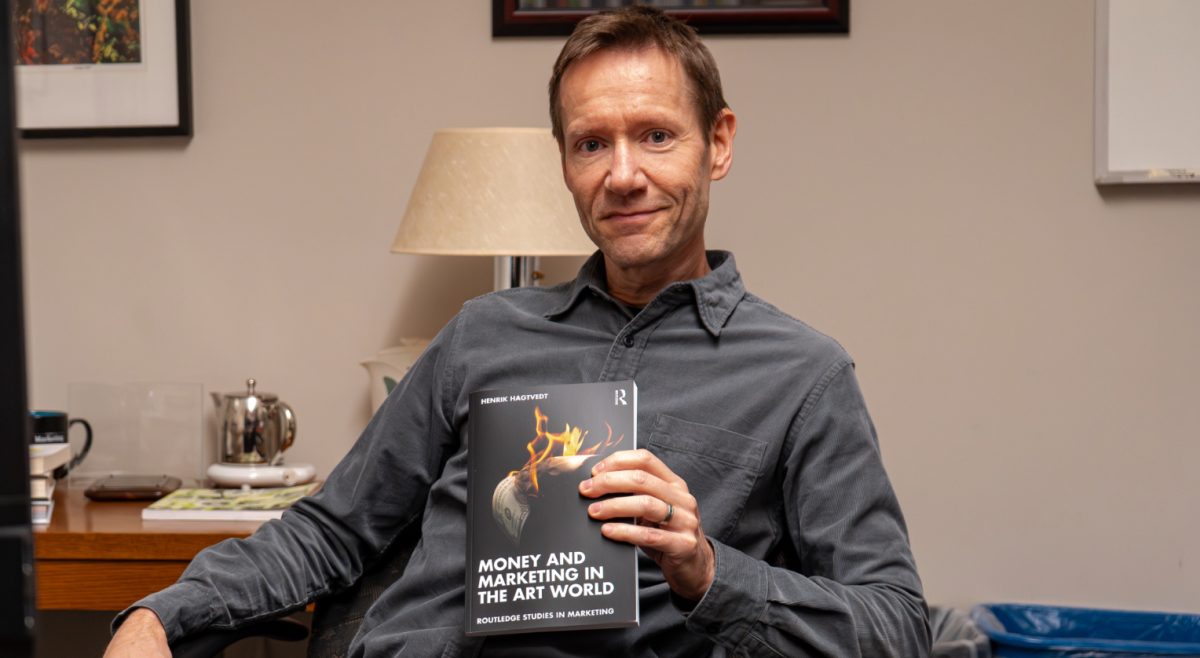

Featured Image by Sam Zhai / Heights Staff