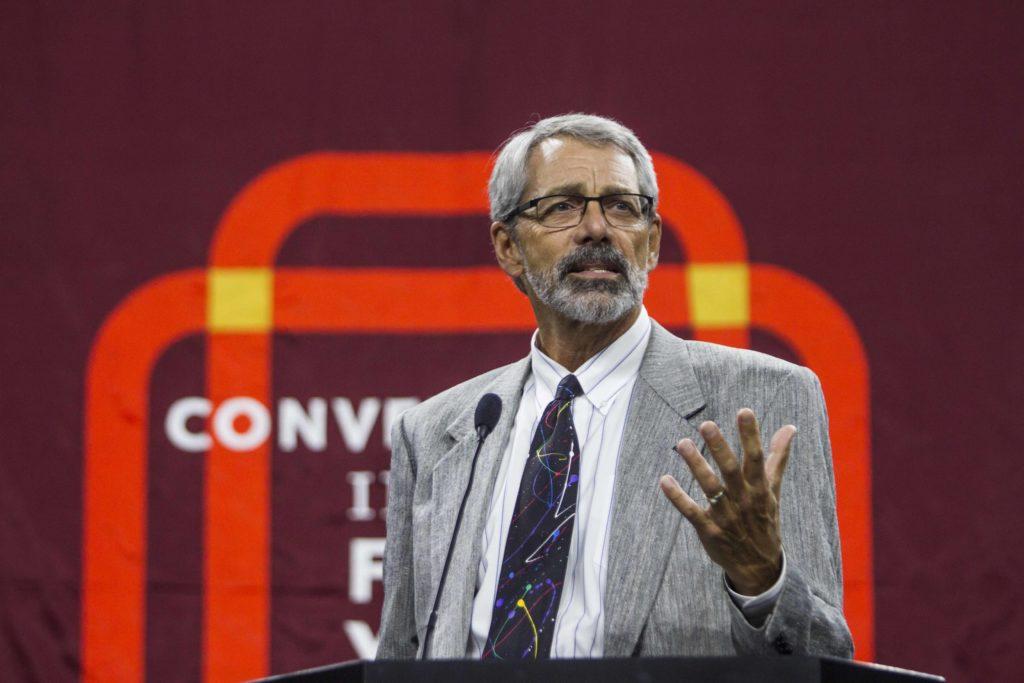

University President Rev. William P. Leahy, S.J., addressed the flock of freshmen clustered in Conte Forum this past Thursday at First Year Academic Convocation. A maroon tapestry cloaked the bottom of the platform, emblazoned with the phrase: Go set the world aflame.

“What we want you to talk about is: How do you use the experiences of your life, and make conscious choices, be intentional, and then link that with your hopes and dreams?” Leahy said.

From the moment they begin at Boston College, the importance of finding their callings is drilled into each freshman class. Strolling down Linden Lane in their Sunday best for the first flight procession, palpable energy permeates the air. Most students leave the night feeling empowered and ready to take on the world—or at least college.

After the glimmering memories of the night fade, however, students are confronted with the four years ahead and the mounting pressure to find internships, join clubs, and secure a successful career after graduation. All the while, the Jesuit value of vocation adds tantamount tension.

This career confusion is all too familiar to Stanford University professor Dave Evans. While studying at Stanford in the 1970s, Evans began his undergraduate career with plans to be a marine biologist. As he lagged behind in labs and struggled to complete problem sets, however, he realized he was miserable.

He soon identified a deep desire: He wanted to solve the energy crisis. He started taking classes he was truly interested in and, after he graduated from Stanford with a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, felt ready to lend his talents to the field of alternative energy.

“I’d found a passion, I had a deep sense of vocation when I graduated from Stanford in 1976 … I’m all cranked up and I’m ready to solve the energy crisis,” Evans said. “What was not in the brochure was the world wasn’t ready to do it. And after four years of failing miserably, I was dead right … we could have made a difference, just put me in coach, but the world never put me in, because there was nothing happening.”

Realizing his calling had come before its time, Evans took a job at Apple, Inc., bringing laser printing public and spearheading product marketing for its mouse team. After co-founding Electronic Arts, Inc., Evans worked with nonprofits, startups, and individuals to help them produce productive and fulfilling work.

This eventually led him to the University of California, Berkeley—where he taught courses such as How to Find Your Vocation—and finally to Stanford, where he currently teaches a course entitled Designing Your Life alongside fellow professor, Bill Burnett.

He went on to co-author the how-to book, Designing Your Life, with Burnett, based on his course. BC’s Class of 2022 read the instructional guide for convocation. Unlike many readings assigned to past classes, Designing Your Life isn’t a novel, nor a biography.

In his keynote address, Evans boiled the 272 pages of the book down to one sentence.

“Get curious, talk to people, try stuff, then tell your story.”

The book introduces the theory of design thinking—similar to the way face recognition on the iPhone X provides security and efficiency, or the floor plan in Walsh Hall was constructed to comfortably house 800 sophomore students, one can craft a life they find fulfilling and meaningful.

“A well-designed life is a marvelous portfolio of experiences, of adventures, of failures that taught you important lessons, of hardships that made you stronger and helped you know yourself better, and of achievements and satisfactions,” Burnett and Evans wrote in Designing Your Life.

The authors—as both professors, parents, and college graduates—empathize with the pressures on students to be successful and discover their dream jobs before donning their caps and gowns at commencement.

The guidance provided in the book helps readers find genuine gratification through pragmatic approaches, in the form of exercises they can use to “design their lives”—such as prototyping, Odyssey Plans, and Life Design Interviews.

“Right now, there’s a fundamentalist philosophy around … you’ve got to be changing the world, and you’ve got to be making an impact, and you’ve got to be passionate,” Evans said. “That mindset can be debilitating, because it’s not that easy to come by. Bill and I are kind of getting a rep as the anti-passion guys. We’re not anti-passion, we’re anti the presupposition that passion precedes everything … very often the passion is what you get at the end. You learn how to love it over time.”

Addressing the Class of 2022, Evans embodied these themes and curated a list of lessons he learned through his experiences as both undergraduate and as a professor who has taught thousands of students.

First: “Seek to get more out of college, not to cram more into it.”

Evans compared working through college to eating an enchilada: You can’t eat the whole thing and be satisfied. Considering how many different opportunities across different colleges and student organizations are available, Evans stressed that entering freshman year with a more focused mindset will engender the results students will really value.

Second: “Curate your curiosity, don’t just collect credentials.”

As the first mind-set of design thinking listed in Designing Your Life’s introduction, thinking like a designer is impossible without first becoming curious. This inquisitive spirit will enable students to see opportunities everywhere, rather than focus on fulfilling requirements.

The third lesson: “Be surprised by joy, not merely satisfied with success.”

By giving themselves permission to take chances and make mistakes, they will inevitably discover new interests.

Evans’ final lesson?

“Don’t just find your way, learn how to be a wayfinder.”

He encouraged the freshman class not to share his snafus from the first two and a half years of his undergraduate studies.

“Let’s aspire to living meaningfully,” Evans said. “We talk about living a coherent life. And a coherent life is one where who I am as a person, what I believe in, care about, value, and what I’m doing are aligned. They make sense one to the other.”

So while the rousing rhetoric of convocation will inspire many to claim their callings and “Go set the world aflame,” Evans wants students to know that it’s human to simultaneously feel lost or overwhelmed.

“What you really ought to be doing [at BC] is growing into the person who if life or the Holy Spirit has something to say to you by the time you’re 28 or 32 … who can hear what you need to hear from life at the point life is willing to tell you,” he said.

Featured Image by Kaitlin Meeks / Heights Editor