Karen Bradley, the secretary of state for Northern Ireland and MP, came to Boston College on Tuesday night to host a talk concerning the looming pressure of Brexit and the lack of a functioning government in Northern Ireland. Although the event later devolved into a contentious question-and-answer session, the evening began with a lighter tone, in which Bradley laid out her perspective on the pair of pressing issues surrounding Northern Ireland.

Unlike in the United States, a secretary of state doesn’t describe one specific member of the executive branch in Northern Ireland. Instead, every Cabinet member is the secretary of state of his or her department. As secretary of state of Northern Ireland, Bradley is tasked with moving between the devolved government of Northern Ireland and the government of the UK and relations with the Irish government. As such, she works for the central government, not Northern Ireland’s.

The Northern Ireland Act 1998 gave Northern Ireland jurisdiction over “transferred matters,” which are economic or social issues, local government, and, later, criminal justice. Other “excepted matters” concern national interest, including international dealings, elections, armed forces, and currency are under the jurisdiction of the UK Parliament. A third category of “reserved matters” encompasses issues that the Northern Ireland Assembly can legislate with the consent of Parliament, like import and exports, firearms, and international trade.

This distribution of power is known as “devolved government.” It differs from the separation of state and national power because the central government can reclaim power at any time. Any topic not specifically designated as an excepted matter falls to the government of Northern Ireland.

Bradley has been thrown into the unorthodox position of representing a government that doesn’t exist. In January of 2017, Martin McGuinness, a member of the nationalist Sinn Féin party, resigned his post as Deputy First Minister following a scandal. Northern Ireland’s government requires that unionists and nationalists come together to share two coequal executive offices. McGuinness’s resignation was a protest against his unionist counterpart, First Minister Arlene Foster, after it came out in 2016 that she had been involved in a major scandal.

Sinn Féin refused to replace McGuinness, who had held the office for the full 10 years following the last power-sharing agreement. As a result, Foster was stripped of her title and the Northern Ireland Executive collapsed. The March 2017 general election left the largest unionist party, the Democratic Unionist Party, without a majority of seats for the first time and only a one seat lead over Sinn Féin. The two parties have been unable to come to a new power-sharing agreement, shutting down the government for over 600 days, beating out Belgium for the shutdown record.

“I have no executive power whatsoever in Northern Ireland,” Bradley said. “We just had a court case judgement in March and it was very clear: the secretary of state cannot direct the civil service in any way in Northern Ireland.”

Bradley attempted to restart talks as a representative of the British government upon taking office. For the time being, Parliament has been extremely limited in dealing with Northern Ireland’s problems due to the strict nature of devolved government.

While the streets are still swept and schools still open their doors, the lack of governance has had major effects. Bradley gave the recent example of Belfast’s Primark building, a historic bank in the center of the city, which burned down in late August. Without a minister to detour the bus routes that run through the area, there has been no way for people to get around the city.

Although Bradley shared her frustration with the effects of the shutdown, she remained steadfast in her belief that the UK government shouldn’t help that much, even if it could.

“Actually if we took some of the difficult decisions in Westminster and somehow got them through, I think it would be harder to get devolution back, because actually why would you come back into government if you’re a politician in Northern Ireland if the difficult stuff is being done in Westminster?” she said. “Policies should be made by ministers who are people who were elected by the [citizens] of Northern Ireland.”

The fractured government comes at a perilous political and historical moment in Europe as the March 29, 2019 deadline for Brexit approaches.

“The way I describe it to Cabinet colleagues is that every impact of Brexit is more acute in Northern Ireland,” Bradley said. “That’s just the facts of the geography. When you’re talking in the [Great Britain (GB)] context about migrants traveling across the sea or across air, because they can’t get to GB any other way. Well in Ireland, people come out of their front door in an EU country and will drive across the order to go to work in the UK, Northern Ireland.”

In her eyes, a Brexit plan that ignores the reality of the situation would create an enormous burden for Northern Ireland.

“And then we have the border, which is the thing that has focused people’s minds and attention,” Bradley said. “The position of the UK government is that we are adamant that we will not allow a order to be put on the island of Ireland. But we also, as a sovereign country, cannot accept the idea that we will have part of the United Kingdom in a separate customs territory from the rest of the United Kingdom and have a border down the Irish sea.”

Despite these tensions, Bradley doubled down on leaving the EU, emphasizing the referendum’s high turnout as a source of great legitimacy.

Bradley promoted the Chequers plan as the only framework that properly addresses the concerns of Northern Ireland. Prime Minister Theresa May has championed the deal as protecting the customs unit, which would maintain the free market relationship currently in place and consequently save Northern Ireland from a border. The deal would also allow the UK to negotiate trade deals on its own and escape many of the rulings and regulations created by the EU. Finally, Chequers would empower the UK to control migration yet keep the free movement for EU citizens.

Some members of her party, however, have voiced support for a “hard Brexit,” which would completely sever any ties at all between the UK and EU, especially the single market and customs union at the cost of a hard border for Ireland.

May met with EU leaders last week in Salzburg to push Chequers, only to be met with a forceful rejection of the plan by European Council President Donald Tusk.

“While there are positive elements in the Chequers proposal, the suggested framework for economic cooperation will not work,” Tusk said at a press conference. “Not least because it will risk undermining the single market.”

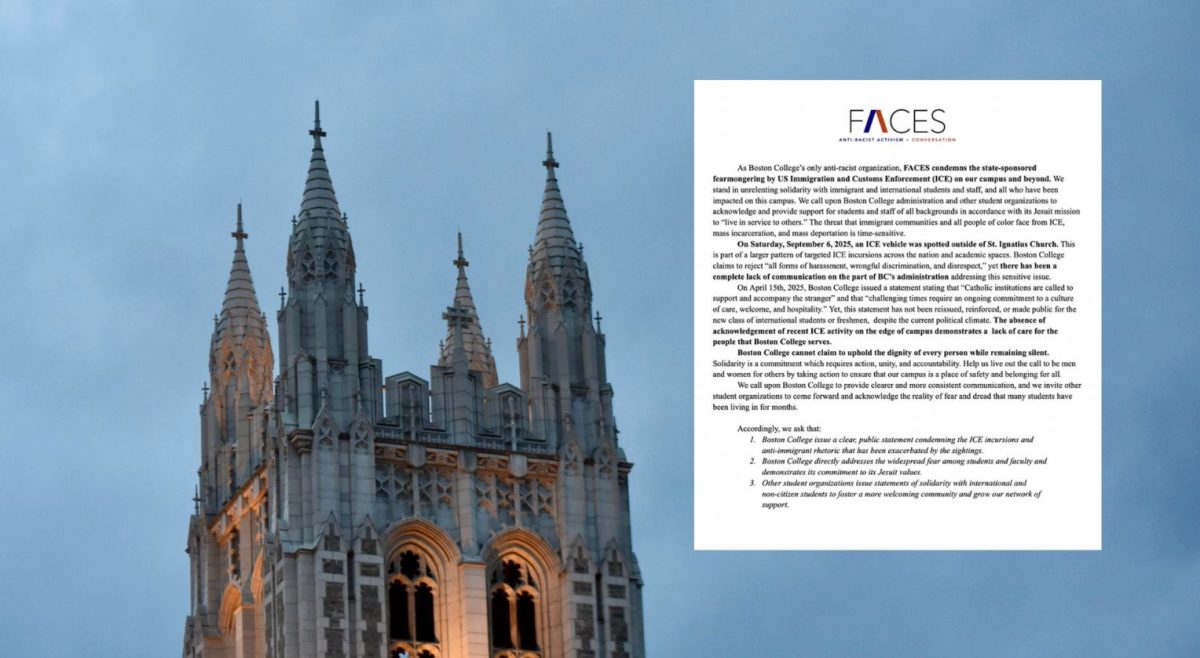

Featured Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons