Fill up the tank / Step on the gas / Today is your day / While supplies last, the five-piece band occupying stage left sings. Its collection of wistful, ’70s-inspired R&B songs is somehow the perfect accompaniment to the tale of two women whose lives intersect in a fictional Rust Belt city in the 1990s—the story told by Manual Cinema’s The End of TV.

Flo, suffering from dementia, spends the lonely days of her old age in front of the television, filling her home with QVC products as her reality becomes tangled with the commercials and shows she sees daily on her screen. Louise, a young, hard-working employee at the local auto plant, lives a solitary life in the same town. When Louise gets laid off from the plant, she meets Flo through her new job as a Meals on Wheels driver, and the two become unlikely friends.

But the most fascinating thing about The End of TV certainly isn’t the story—it’s the way it is told. “Manual Cinema” certainly lives up to its name, as the show feels very little like watching a play and far more like watching an animated movie—one that’s being created before your very eyes.

The End of TV has only four cast members, who constantly alternate between acting and shadow puppeteering. Practically seamlessly, they rotate between performing as silhouette actors in front of a projection screen and using old-fashioned overhead projectors to cast background scenes and the shadows of images onto it. All the while, by means of a live-feed camera, the view from behind the projection screen is played on a large monitor above the stage, allowing the audience members to watch the performance as a shadow puppet show when they look up, and the cast’s graceful, tireless movements that go into creating the spectacle when they look down.

Interspersed throughout the story are television shows, advertisements, and infomercials—the relentless background noise of Flo and Louise’s daily lives—that are created on a small “TV set” off to the side of the overhead projectors. These interjections bring small, consistent bouts of comedy to the show, as the cast’s exaggerated performances of various television personas—panicked ER doctors, an overzealous QVC host, and a clueless Today Show anchor, for example—elicit chuckles from the audience.

If the way the storyline, shadow puppetry, acting, and music in The End of TV come together could be described with one word, it would be impressive. The artists bring together the countless elements that go into creating the spectacle so seamlessly that it’s almost hard to believe.

When watching the stage, the audience members are mesmerized by the cast as they effortlessly execute this shadow-based performance. When looking at the monitor above, they become lost in a tale of hope and heartbreak—one that has the look and feel of an award-winning silent animated film.

The audience never hears Flo, Louise, or any of the people in their lives speak, but they don’t need to. The soulful music, the TV chatter, and the talented work of the silhouette actors are all the audience needs to be immersed in moved by Flo and Louise’s journeys and the despair, hope, and confusion the two experience along the way.

The End of TV isn’t the first show Manual Cinema has created using this unique design, but the medium is certainly perfect for it. It’s able to reflect exactly how reality feels for Flo as her life becomes intertwined with her television—each thing the audience watches the artists do in real life is inextricably tied to what is happening on the giant TV-like screen above them.

While it’s set in more than 20 years in the past, the show is all too timely for us in the age that has met the end of TV and encountered even more all-consuming replacements in laptops and smartphones. In an era where you only need to reach into your pocket to access the internet’s deafening din, Flo’s experience has become much more of a universal one. It turns out that with the end of TV, the lines between media and reality have only become all the more blurrier.

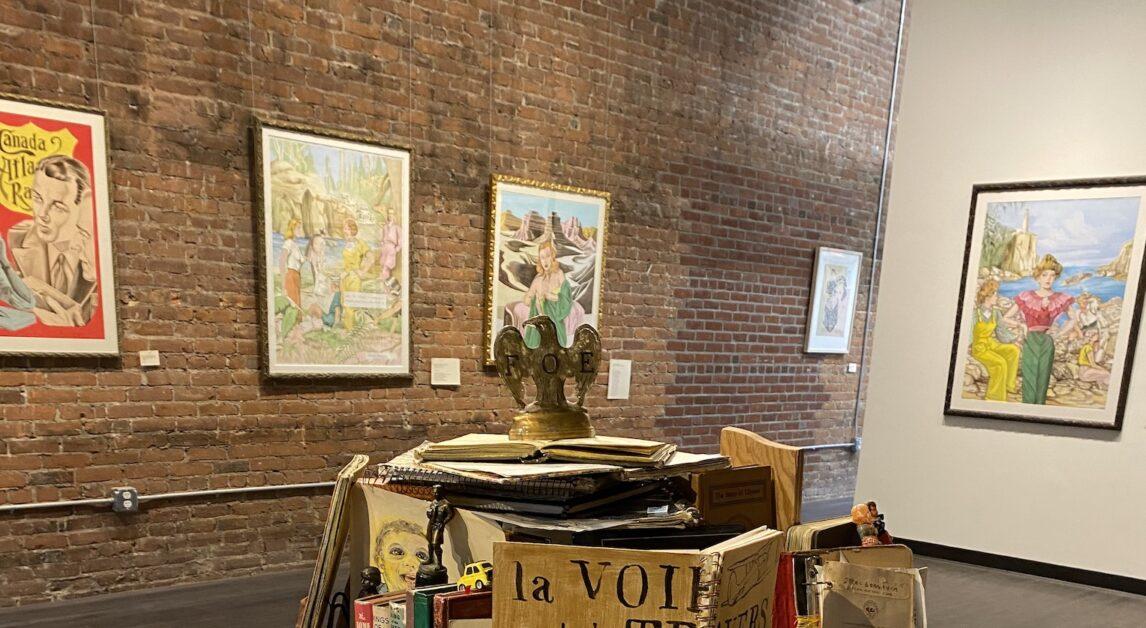

Featured Image Courtesy of Judy Sirota Rosenthal