During his presentation for the art department’s Currents lecture series, Sosa discussed how he integrates text into pieces like this one, exploring the interplay of language, memory, and public art. At the virtual event on Thursday, Sosa guided the audience through his multimedia work. He discussed how his constant examination of language has led him to create public art displays that are now displayed on billboards in East Boston and Roslindale Square.

Sosa was initially hesitant to incorporate text into his artwork, believing that it did not leave room for interpretation. His work in the courtroom, however, where he translates English to Spanish for defendants and witnesses, inspired him to think about how language allows people to express their memories.

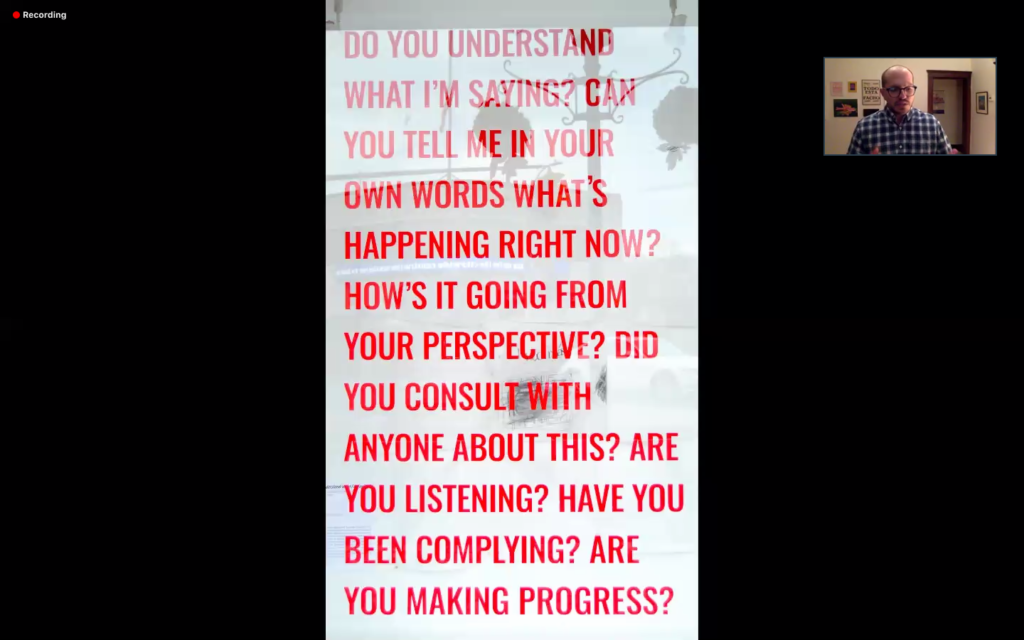

The first piece he shared featured a white canvas with short phrases spread across in bold red lettering. Sosa took passages written in Spanish from letters that he translated from defendants’ friends and family members who act as character witnesses for defendants.

Intrigued by the stories that people recalled in their letters, Sosa began questioning people’s relationships to their own memories.

“They have given me pause to think about how it is that we remember others, how it is that we use those memories to define others and also to define ourselves,” Sosa said.

Working closely with these letters prompted Sosa to think about his own ties to his heritage and language. As a Cuban-American raised in Miami, Sosa grew up hearing about his family’s life in Cuba before they were forced to flee from the Cuban revolution in 1959. A letter from his grandfather in which he reflected on the pain of leaving his home inspired Sosa’s video piece 5,382 Días De Ausencia (5,382 Days of Exile), in which he layered audio of him reading his grandfather’s letter over an episode of the 1970s bilingual sitcom ¿Qué Pasa, USA?

Sosa explained that he paired this letter with the television show about a family with multiple generations of Cuban-Americans because it allowed him to play with the relationship between sound and image. The piece also makes a statement about the indelible connection he and his family have to a place where they no longer live.

“All of us who grow up Cuban in Miami constantly hear these stories where Cuba becomes a legendary place,” Sosa said. “It’s always there but it’s not. It’s always present, always influencing you.”

Sosa presented other works that incorporate photographs of his family and audio of his aunt reflecting on growing up in Cuba. After considering the relationship between text, language, and his own family’s history, Sosa concluded that the memories these forms represent are inextricable from people’s understanding of their own world.

“For so many of us our memory becomes our own reality, whether or not it’s right,” Sosa said.

As Sosa began incorporating more text into his work, he discussed public pieces that that have been displayed on buildings in California, Colombia, and shop windows in Boston.

The lecture concluded with a discussion of Sosa’s current public art project No Es Facil/It Ain’t Easy. The pandemic and new social distancing regulations forced Sosa to reconsider how people can interact with public spaces. He settled on colorful billboards placed primarily in Boston neighborhoods with a significant immigrant population as the best medium to communicate short phrases in English and Spanish such as “it ain’t easy, but keep going.” Thinking about the role of the artist during this tumultuous time, Sosa wanted to provide hopeful words to communities where many people are essential workers.

“Whenever people come across these in their ambiguity, I hope that when they see these billboards, there is that little bit of confusion,” Sosa said regarding reactions to his work. “But whether something big or small, it’s just kind of that thing that someone needed to hear in their day.”

Screenshot by Katherine Canniff / For The Heights