Many college students arrive on campus feeling pressured to have their futures figured out. Many also feel that they’re already several steps behind in achieving their goals.

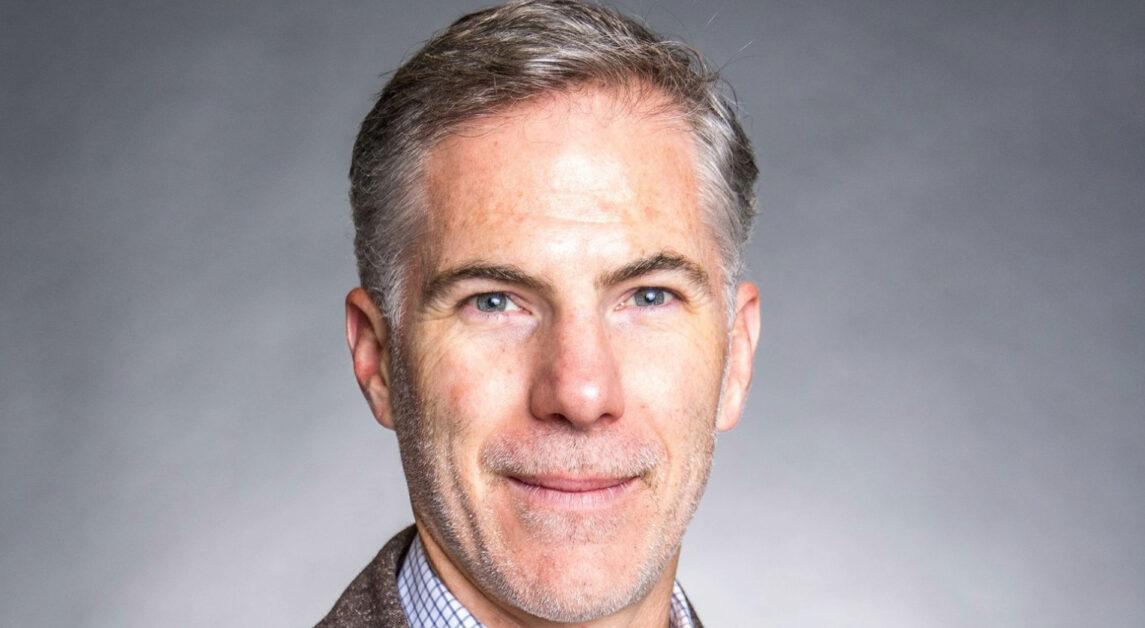

In his new book, Undeclared: A Philosophy of Formative Higher Education, Chris Higgins, associate professor and formative education department chair in the Lynch School of Education and Human Development, seeks to reframe this common narrative that shapes the college experience.

Higgins focuses on what it would look like to educate the whole person by encouraging their holistic development, rather than steering them down a narrow track.

“What inspired me to write was a growing sense that we were losing sight of the idea that college could be and should be a space for exploration,” Higgins said. “I was starting to see this attitude that was kind of this culture of you’re supposed to pick a lane and put on the gas.”

Higgins began writing Undeclared while teaching at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he taught from 2006 to 2019.

The spark for the central ideas of the book came when Higgins met with a student whose “undeclared” status led to anxiety about finding a path of interest. The student had followed Higgins to his office hours after class, hoping to discuss the issue.

“I said, ‘What’s going on? What’s wrong?’ And he mumbled something. I still couldn’t quite hear,” Higgins said. “Finally, he told me his deep, dark secret was that he was undeclared. He felt somehow there’s a stigma attached to the fact that he had come in as a computer science major, but he hadn’t liked it, and he hadn’t yet found the thing to switch to.”

Higgins’ meeting with the student led him to realize that while being “undeclared” often carries negative connotations, it actually signifies the ability for greater exploration.

“He was temporarily undeclared, and it just clicked to me in that moment that it’s a beautiful thing to be undeclared,” Higgins said. “It’s the true spirit of college to be on the hunt, to be searching, to be full of questions, to be exploring all kinds of potentials in yourself, rather than locking yourself into one vision of who you are.”

The book is made up of three long essays and three shorter interludes. Each focuses on the current state of higher education and explores questions about the purpose of incorporating various types of education.

“The tradition of the essay is really different from a lot of academic writing, because it embraces the idea that the author is not just an expert holding forth on some topic, but him or herself searching,” Higgins said.

In the first long essay, “Soul Action: The Search for Integrity,” Higgins explores what it means to teach a person holistically. In the second, “Wide Awake: Aesthetic Education at Black Mountain College,” he takes an experiential approach to higher education, using Black Mountain College—a university active in North Carolina from 1933 to 1957—as an example.

“I take the reader back to look at how they built an institution centered on the arts, centered on the education of the whole person, democratically self governed, where everybody on campus shared in the work,” Higgins said.

Finally, in the third essay, “Job Prospects: Vocational Formation as Humane Learning,” Higgins asks how universities can help students discover their vocation without making career preparation the only focus, or pushing them to shape their identity solely for the job market.

“How could college education be not some kind of abstract thing that doesn’t help you figure out your vocation, but also not what I call ‘jobified,’ where it’s understood that you’re on a track and everything should be about credentialing or training for that particular job that you have in mind?” Higgins said.

During his time at Illinois, Higgins found himself in the minority, advocating for colleges to place more emphasis on students’ personal growth.

“I thought, ‘There’s plenty of people trying to make college more streamlined, toward a job,’” Higgins said. “I’m going to be a counter voice that says it’s not only okay, but good to be a searcher.”

As he began looking for new job opportunities elsewhere, Boston College’s learning environment resonated with his concerns about the state of higher education.

In particular, he was drawn to BC’s Jesuit tradition and the work of Stanton Wortham, the inaugural Charles F. Donovan, S.J., dean of LSEHD.

“When I saw the description, it just seemed like a place I’ve been waiting for, a place where it’s understood that questions of meaning, value, and purpose are central to educational discussions, and you don’t have to try to apologize for an interest in the big questions about education,” Higgins said.

Cristiano Casalini, Professor, research scholar at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and endowed chair of Jesuit pedagogy and educational history, has known Higgins since he first arrived at BC.

Casalini noted that Higgins’ engagement with students and programs directly reflects his thinking about what a university should be.

“He is someone who is really incarnating the questions that he poses intellectually as a formative educator,” Casalini said.

Casalini also highlighted how Higgins’ intellectual work aligned with his efforts at BC. He described Undeclared as the culmination of everything Higgins has done professionally, both in the classroom and in collaboration with colleagues.

“The topic that he was dealing with resonated with this, with his classes, his advising, his articles and papers that he had published about what it means to be an educated person, what it means to be an educator,” Casalini said.

Higgins’ own undergraduate experience at Yale University revealed to him how universities often fall short in fostering students’ growth, but it also fueled his excitement about the opportunity to become an educated person.

“One of the deep inspirations for this book was coming out of high school and feeling like something was missing in the model of education or high school, and then finding that what was missing is some language for what this all means,” Higgins said. “What does it mean to be liberally educated?”

By relying on a meritocratic system, colleges often instill a mythos in students about the purpose of their time at the school, framing academic success as a direct path to the job market.

Higgins cited Excellent Sheep by William Deresiewicz as a compelling exploration of how habits formed during the college admissions process and the way students navigate their college campuses and careers.

“In Excellent Sheep, he makes the argument that it’s not surprising that if you make a high stakes game of hoop jumping the prerequisite for landing a spot in an elite, highly selective university or college, it’s not a surprise that when students arrive on campus, they’re going to be looking for more hoops to jump through,” Higgins said.

According to Higgins, the formative benefits of education come from how we approach our educational experiences and the way the university defines education more broadly.

As an example, Higgins emphasized the importance of viewing a core curriculum as an opportunity to grow in different areas, rather than as a burden for students to trudge through. He also cites the connection between a college and its physical location as another key factor in students’ educational experiences.

“Are we really clear that we’re here in Chestnut Hill, here in Boston, or do we act sort of like a bubble, as people like to say?” Higgins said.

Erik Owens, professor of the practice and director of the international studies program, works with Higgins.

Owens reflected on Higgins’ efforts to share his ideas on formative education throughout the BC community.

“He knows it’s meaningful for society, and he’s working on it across all the areas of his profession, writing about it, trying to build institutions around this commitment, and creating spaces where everyone can reflect on that as well,” Owens said. “It’s terrific to have a colleague that’s committed to big ideas that are so good for our community to take up.”

In addition to his role in the Lynch School, Higgins collaborates with the Division of Student Affairs to bring elements of formative education into residential life at BC.

He offers a course called “The Educational Conversation,” designed specifically for residential assistants, which encourages student leaders to see their roles as more than just policy enforcement.

“How do you accompany others on their formative journeys, sort of between friendship or mentorship? Higgins said. “What does it mean to be there for somebody else as they work to give shape to their character, their moral compass, and their life?”

Whether in LSEHD or the Division of Student Affairs, Higgins promotes his views of holistic growth through learning across all domains. Owens said Higgins often encourages his departments to reflect on their engagement with each other and with education.

“He has a sense of what’s important to be working on,” Owens said. “That’s important because he is helping us be more reflective and considerate in the way that we do what we do in higher education, the way that we educate, and think about the way that we treat one another and our students.”

Ultimately, Higgins seeks to transform educational systems by shifting the focus from quantity and appearance to the quality of students’ development as they transition into adulthood.

“It’s the true spirit of college to be on the hunt, to be searching, to be full of questions, to be exploring all kinds of potentials in yourself, rather than locking yourself into one vision of who you are, or one track,” Higgins said.