Gone Girl speaks to director David Fincher’s affinity for the dark. From The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo to Se7en to Fight Club, Fincher repeatedly delves into the minds of psychopaths and serial killers. Based off of Gillian Flynn’s complex, haunting New York Times bestseller, Gone Girl keeps with Fincher’s morbid themes.

The story revolves around a married couple, the perfectly cast Nick (Ben Affleck) and Amy (Rosamund Pike), who have gone through some rough times. Nick loses his job and then his mother, meanwhile forcing his wife to relocate from New York to his rinky-dink hometown in Missouri. Amy, also suffering from a layoff, agrees to the move in part to get away from her manipulating psychiatrist parents.

Upon arriving in Missouri, however, things only get worse. Nick refuses to find a job—in one scene, he is shown finding refuge in video games and Chinese takeout. Once he does find employment, it is through Amy’s trust fund, as she gives him the money to start his own bar. But bitterness divides the couple, and soon Nick turns to a hot young thing to keep his mind off of it.

On Nick and Amy’s fifth wedding anniversary, Nick comes back to the house to find what seems to be a crime scene—someone has made a mess of his living room and has taken Amy. He immediately calls the police, and an investigation ensues.

Although not told from Nick’s perspective, Fincher’s film sympathizes with the husband from the get-go. He clearly has a temper, he cheats on his wife, and all clues point to him. But, never for a moment do you think he did it. Even with Rosamund Pike’s haunting voiceover and Nick’s continued missteps, it’s almost impossible to align with any side but his.

Fincher’s talent resides heavily in his ability to take a seemingly traditional story and make it anything but that. While technically in the murder-mystery genre, clues and investigation take a backseat to the media scrutiny surrounding Nick, deviating from the traditional whodunit. Fincher hires a lawyer, who focuses less on evidence and more on media interviews.

Meanwhile, Amy, alive and well, heads to a motel, where she befriends some morally questionable residents and speaks with a terrible New Orleans drawl. Pike’s cold, beautiful exterior makes it easy to antagonize her, as does her psychopathic need to destroy her husband’s image.

As the film progresses through its excessive two-and-a-half hour runtime, the distractions begin to add up. Tyler Perry stars as the lawyer famous for defending wife-killers, while Neil Patrick Harris appears as Amy’s former boyfriend. These jarring casting decisions distract from the tension Fincher meticulously builds up. And, as the plot begins to gain speed, Amy’s actions seem more humorously absurd than serious.

Undeniable is the film’s precise editing and visionary cinematography. With a little help from familiar faces (he’s worked with cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth and editor Kirk Baxter many times before), Fincher plays on his strengths in Gone Girl. His precision is unparalleled, and in anyone else’s hands, the twists and turns of Flynn’s masterfully complex screenplay most likely would have been messy. Most exceptional is the unconventional score, which maintains the tension throughout the film using electronic beats and pulses. And, despite his casting mishaps, Fincher also showcases some talent in Kim Dickens as the strikingly aware head investigator, and Carrie Coons as Nick’s loyal sister.

Despite almost all of Fincher’s films having the same dark, twisted nature about them, it is interesting to note that his best film, The Social Network, is also his lightest. Gone Girl is surely fun, but it’s only in the finale that Fincher finds something truly great. Fincher uses this film as his own take on the inner workings of relationships in this modern era. And what he finds—deception, connivery, and plenty of self-consciousness—does not bode well for our generation.

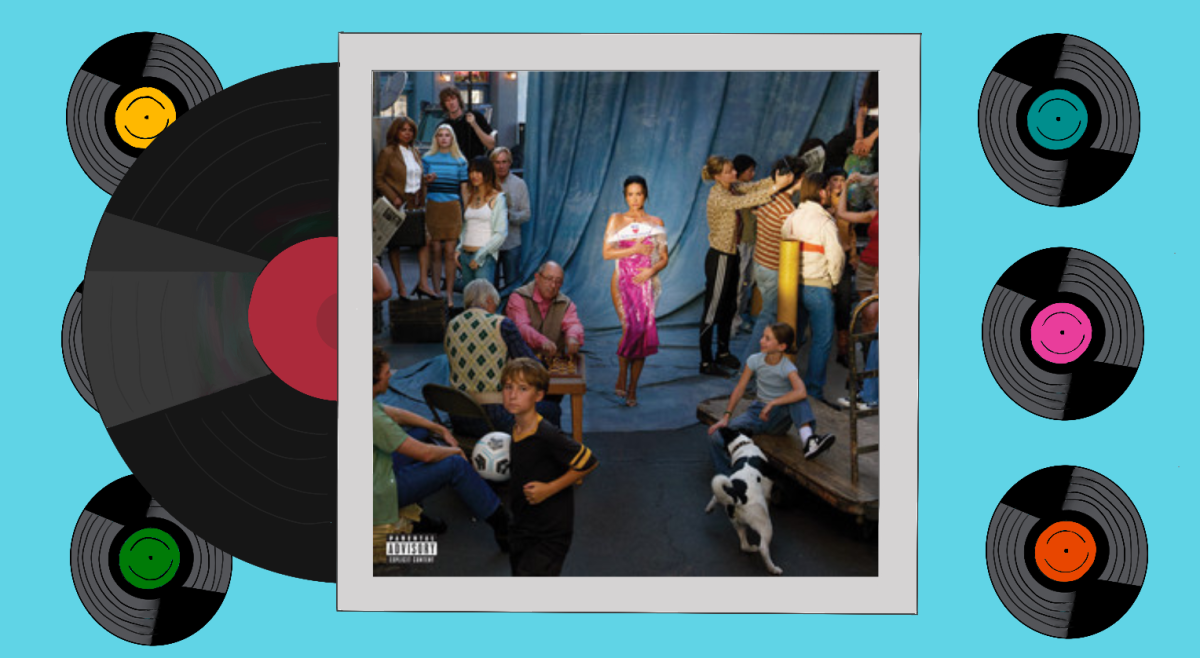

Featured Image Courtesy of New Regency Pictures