Through Jan. 29, the Black Spaces Matter: Exploring the Aesthetics and Architectonics of an Abolitionist Neighborhood exhibit at the Boston Architectural College McCormick Gallery is using historic New Bedford’s architecture to tell the story of its former residents: abolitionists, freed slaves, and African Americans.

“There’s a storytelling theme that goes with architecture,” said Pamela Karimi, associate professor of art history at UMass Dartmouth and lead curator of the exhibit. “I hope that this exhibit opens the door for new ways of exploring architecture. We shouldn’t just look at cutting-edge design. We should look at the stories that go with them.”

The exhibit originated in 2012 at UMass Dartmouth when Karimi tasked students in her “Architecture and Sustainability in the American Post-Industrial City” class with designing a solution to better the lives of New Bedford citizens. Students with backgrounds in a variety of disciplines collaborated on projects that focused on all aspects of design, including art and architecture.

After receiving a grant, the class held a series of lectures and exhibitions to highlight their projects. Later, the class began to focus on designing plans to repurpose a series of vacant lots in historic New Bedford, specifically a lot that was the home of Frederick Douglass. Students presented their proposals to community stakeholders and the president of the New Bedford Historical Society, all of whom were impressed by their work.

Karimi’s team then began looking for a venue to showcase the work, and they found the perfect location at the McCormick Gallery. Wanting to present the project to the entire state of Massachusetts, the McCormick Gallery’s location on heavily trafficked Newbury Street provided the necessary visibility and public access.

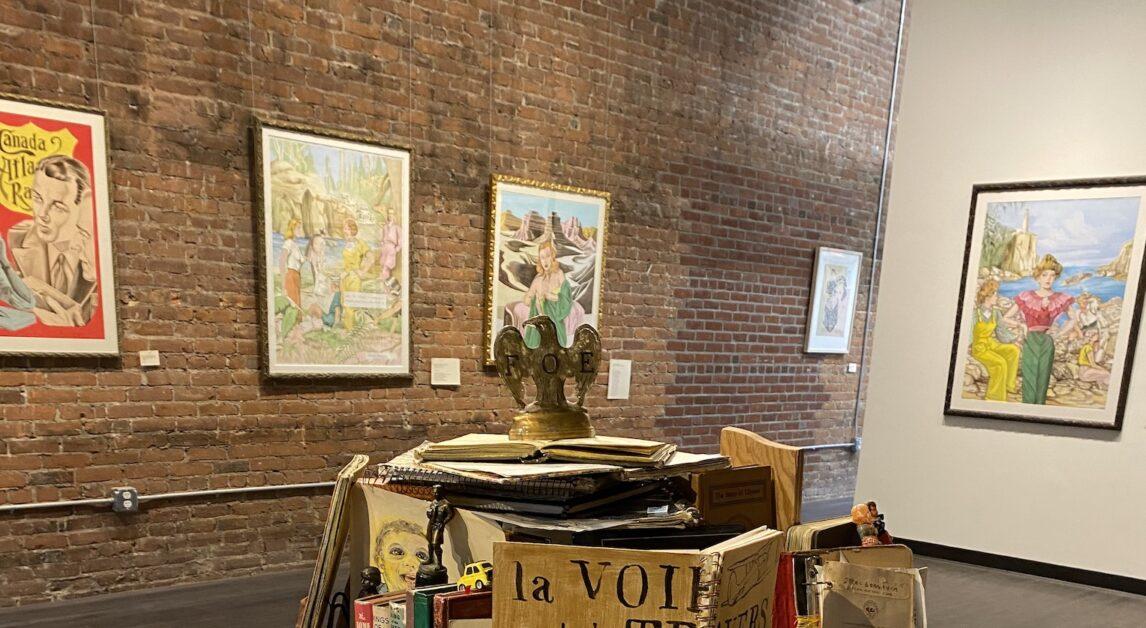

At the exhibit, there are three panels that showcase a sample of the student projects, while the remainder highlights broader topics related to New Bedford’s past, present, and future. Visitors to the exhibit can watch videos featuring current residents of New Bedford, as well as Karimi’s explanation of the origins of the project. In other videos, specialists speak on the importance of bringing African American culture to light.

A virtual reality portion of the exhibit allows visitors to look out over New Bedford. A three-dimensional model of the neighborhood points out which homes once belonged to prominent figures, while an interactive digital map gives visitors the opportunity to look inside the homes.

Maps of New Bedford, photographs of important local historical figures, images of significant homes that span centuries, and other artifacts explore the town’s rich whaling history, an industry that brought many African Americans to the area with its promise of employment.

The exhibit also looks toward the future with a mural of Douglass that strives to ensure he remains an important aspect of New Bedford and a proposal for an abolitionist park in the neighborhood.

According to Karimi, although the New Bedford homes featured may seem to be of little architectural importance, the story behind them is one that needs to be told. In past decades, historical societies have made little effort to preserve the material culture of African Americans because their neighborhoods are usually modest and poor.

“What we wanted to do through this show was to say that even though the architecture is not significant, even though we cannot necessarily learn something about glamorous styles of architecture or cutting-edge ideas in architectural design, we can still celebrate these spaces of everyday life of abolitionists and African Americans,” Karimi said.

One of the primary ways the exhibit is able to celebrate these homes is through artistic photography. Photographer Michael Swartz used a fisheye lens to bring visual interest to what would otherwise be ordinary photographs of 19th-century cottages.

“People walk into the exhibit and want to look at these photographs even though they’re just a bunch of simple homes,” said Karimi.

Creating the exhibit proved to be challenging, as Karimi’s team did not have any floor plans for the homes. As a result, collaboration with experts in the field was necessary for devising a strategy to accurately document the neighborhood. Don Burton, a filmmaker; Lee Blake, president of the New Bedford Historical Society; Michael Swartz, designer and photographer; Jana Cephas, assistant professor of architecture at the University of Michigan; Pedram Karimi, architect and designer; and Jennifer McGrory, architect and manager of exhibition production, were instrumental in making the goal for the exhibit a reality.

According to Karen Nelson, dean of the School of Architecture at the Boston Architectural College, the Black Spaces Matter exhibit is the first the institution has hosted that is entirely dedicated to African American spaces of historical significance.

“I think [the exhibit] answered an unmet need in the student body, which is very diverse, and diverse for New England, and especially diverse for architecture schools … so we’re feeling like it’s part of our mission to do more of this,” Nelson said.

Since the exhibit opened in Nov. 2017, students have expressed an increased desire for African American speakers.

According to Nelson, it has always been a mission of the college to have a diversity of speakers.

“We’re making sure our students feel reflected in both the curriculum and the exhibits,” Nelson said.

Featured Image by Chloe McAllaster / Heights Editor

This post has been updated.

Kath3rin3 W • Jan 24, 2018 at 9:39 pm

Looks a like a great exhibit. Will the work be documented in a permanent form such as a booklet or in the school archives?