Once when I was about 7 years old, my mother—as she did every night after tucking me in—sang me a song. Usually I would listen without complaint, but since I was a difficult child, this night, I felt the need to complicate things.

“Mom, you sang a G#, but it should have been an A,” I piped up in the middle of the lullaby, no doubt patting myself on the back for my constructive criticism.

My mother—bless her heart—instead of losing her temper at her ungrateful child, brought the incident up at my next piano lesson. My teacher had me turn my back to the piano. As she played note after note, I found I could instinctively identify them. It confirmed what she had suspected: I had perfect pitch.

Perfect pitch, also called absolute pitch, is the ability to identify and re-create a musical note without the use of a reference tone. For me, it feels as natural as recognizing colors. Of course, the grass is green. Of course, the walls are white.

Except sometimes, just as during a sunset it can be hard to tell when the sky stops being blue and starts being lilac, things get difficult when notes bleed into each other. Out-of-tune pianos are my kryptonite. In fact, anything that’s not a piano presents a bit of a challenge. The keys of a piano are discrete—there’s no way to play a note between them. Yet with a flute or a violin, it’s incredibly easy to slide from one note to another without even realizing it, or hover somewhere between two notes. Singing voices are even more difficult. The hardest is identifying the pitches of things that aren’t even supposed to be musical: a car horn, the clink of a glass, the bell at my middle school.

I imagine that for those who sing or play an instrument, especially one that they need to tune themselves, perfect pitch can be quite handy. But since I got to college, I’ve neglected the piano. I hardly play anymore. Yet my perfect pitch still clings stubbornly on, as if it’s absolutely necessary I know that “Oops I Did It Again” is in the key of C# minor.

Nobody knows exactly how common perfect pitch is. The figure one in 10,000 is thrown around a lot but hasn’t been confirmed by any major studies. No matter the specifics, it’s rare. I can only recall meeting one other person with perfect pitch. She was in the group of high school nerds, myself included, chosen to travel to Moldova for six weeks for a government scholarship designed to immerse us in “critical languages”—in our case, Russian. It turned out that this girl had two hobbies: bragging about her Spanish proficiency (and Dominican boyfriend) and bragging about her perfect pitch. To be fair, she was in a whole different league than I was. She could pinpoint notes down to the exact frequency in hertz. She was an orchestra kid. Figures.

On our last day in Moldova, we spent hours camped out in the airport waiting for our early morning flight back to Germany. Some incessant little tune played over the loudspeaker at regular intervals. She looked at me and asked what notes they were.

“D-D-C-B-A-B-G-D.”

For the first time, she looked at me with the tiniest glimmer of respect. We nodded sagely to each other, feeling smug with our arcane, absolutely useless knowledge.

I find this little anecdote very effectively communicates the exact nature of having perfect pitch. People assume I’m bragging when I tell them about it, but on its own, it’s nothing more than a neat party trick. It doesn’t guarantee you musical ability, or even a decent singing voice. Things it does bring include the power to tune a guitar by ear, the inability to listen to anything remotely off-key without shuddering, and your own miniature superiority complex. Because at the end of the day, there’s no better power trip than correcting someone’s pitch. Even if that person is your poor mother.

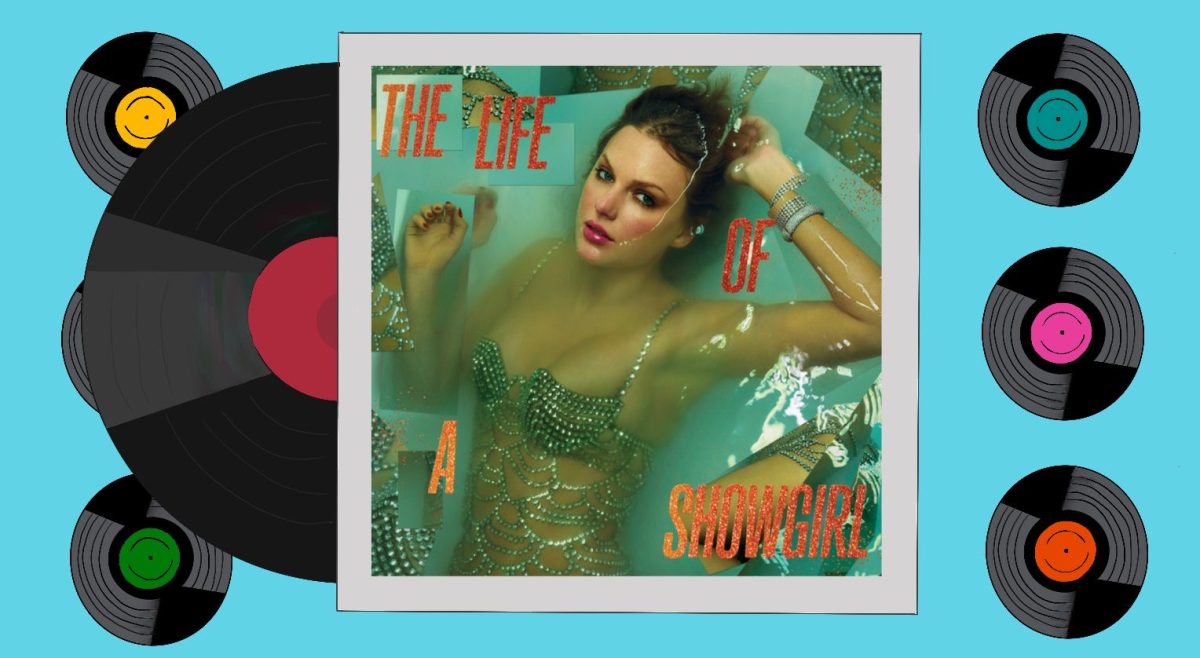

Featured Image by Ikram Ali / Heights Editor