While picturesque natural landscapes remain accessible and revered in modern life, they captivated the attention of some artists starting in the sixteenth century. The McMullen Museum of Art opened their latest exhibit, “Nature’s Mirror: Reality and Symbol in Belgian Landscape” on Sunday, and presented visitors with the origins of landscape art and the aesthetically varied collection of work that the genre contains. Sixteenth century artists in Belgium and the Netherlands created landscape art in response to the infinite variety of nature and the complexities of contemporary cultural and aesthetic shifts. The development of the genre continued into the 19th century, and with it, the form evolved to dialogue with urbanization and the political pressures of the era.

The 16th and 17th centuries hailed printmaking as a prominent artistic medium, and portrayed the bustle of everyday life in the region. Mixing spiritual and empirical influences, the prints could reach a mass audience through production of multiple copies, giving them the opportunity to influence public opinion. One artist, Pieter Bruegel, created allegorical images about virtues in daily life, while Hieronymus Cock published them. In one image, “Allegory of Fortitude,” an angel stands for fortitude amidst a brutal battle scene resembling the conflict of 16th century Belgium. The black and white print is filled with collapsed figures and glinting weapons, while the distant natural landscape is sparse and dotted with sturdy trees. The angel, Fortitude, and the background landscape starkly contrast with the violent chaos that dominates the image, which integrates moral commentary on the contemporary political landscape.

Drawing on realist art of the late 19th century, the symbolists used symbols and allegory to augment their subjective experience of everyday life. Some artists used natural scenes to convey their emotional states, which includes the work of William Degouve de Nuncques. In his painting “Barge on a Canal” of a Belgian farmhouse property, Degouve de Nuncques captures the countryside at dusk. Complete with a modest boat docked in calm water and a rich red farm house, the scene conveys a quiet serenity. The orderly lineup of willowy trees is a glaring contrast from another image, “The Servants of Death (Nocturne).” In the dark, ghostly pastel, Degouve de Nuncques presents a man with a razor-sharp saw carefully ripping into a chained log, presumably for coffins. The nearly monochrome image presents overwhelming mortality salience, and offers a grim counterpoint to the soft, placid scene of “Barge on a Canal.” A foggy, dark pastel, “Canal, Bruges,” casts the glow of a weak street lamp over a mysterious canal. The image conveys a disconcerting amount of uncertainty and ambiguity through the dimly lit landscape, and the pair of figures walking in the shadows accentuates the notion that people can become one with their surroundings. In this case, the landscape grips the figures in its eerie embrace, along with viewers of the painting.

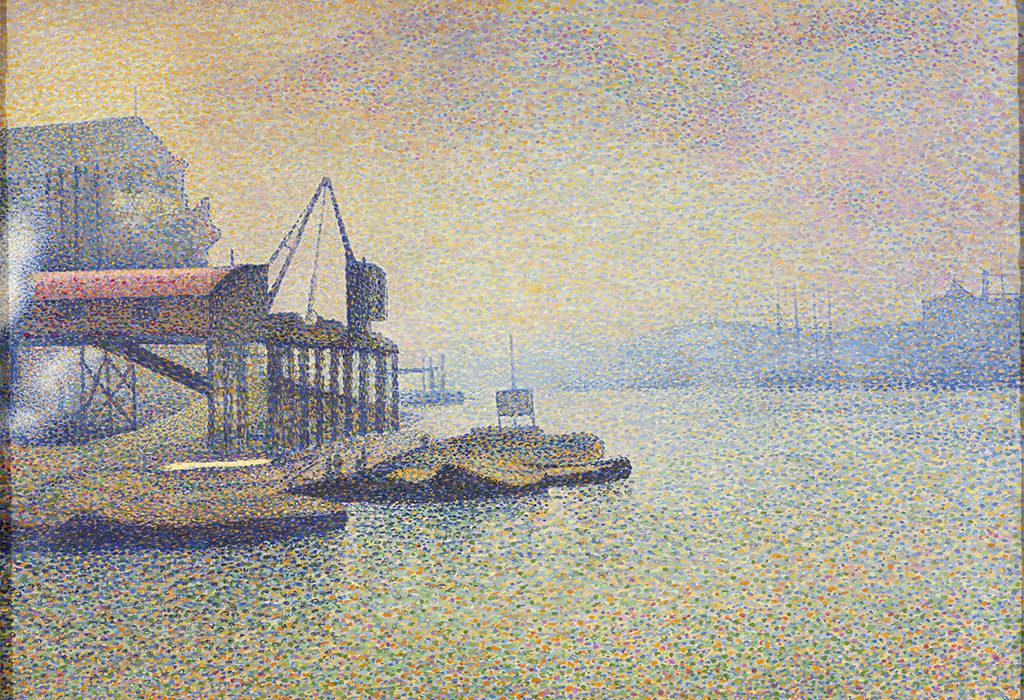

Coming out of the School of Tervuren, other artists of the 19th century created art featuring a balance between agricultural, industrial, and natural landscapes. “Landscape with Pond” an oil on canvas painting by Théodore T’Scharner, highlights the brilliant sun bursting through a mildly threatening patch of clouds onto an earthy marshland. The white, glowing sunlight contrasts with the otherwise muted landscape to draw the viewer to the center of the painting and command their attention. Another work by T’Scharner, “Ships,” features teal, glassy water under dark, jagged ships, which stand out against the visible brushstrokes of the sky. The scene develops a dreamy quality, and allows the ships—the only evidence of human life—to remind the viewer of a concrete, bounded presence in the scene. Franz van Kuyck’s oil on canvas, “Marsh at Twilight” presents another image of a commanding sky over a watery landscape. The stunning painting highlights an iridescent sunset pressing through thick clouds, and delicately glows off of the scarce marsh of the scene. A meager boat gives humanity a presence in the painting, and the work presents the natural world in a soft, warm light.

As a group, the “Nature’s Mirror” collection spans centuries and presents idyllic natural phenomena alongside occasionally grim depictions of daily life. The works are woven together through artists’ dedication to truthful presentations of the world around them and their perception of it. The range of landscapes included in the Belgian art collection showcase are contributions influenced by the romantic and realist movements, which connect the states of human life to the expansive environment in which they live.

Photo Courtesy of the McMullen Museum