On the second floor of the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), a thin sheet of glass and a few feet are the only barriers separating interested museum-goers from the meticulous restoration of two Rembrandt portraits. While these paintings take precedence near the front of the studio, scattered around the gallery is a collection of nearly floor-to-ceiling Byzantine altar pieces that have been in the restoration process for the past few years. Eventually, the space will become the permanent home of these revived altar pieces, and the restoration of the two Rembrandt paintings will move elsewhere, out of the public eye.

For the entire month of February, the public is granted the opportunity to witness the restoration of two Rembrandt portraits unfold in real time in the “conservation in action” studio. The two paintings—Portrait of a Man Wearing a Black Hat and Portrait of a Woman with a Gold Chain—are pendants intended to be hung side by side. Donated to the MFA in 1893, the pieces were the first Rembrandt paintings to join the museum’s collection.

“We are thrilled to have the opportunity to conserve these seminal paintings by Rembrandt, which normally have an important presence in our galleries,” said Ronni Baer, William and Ann Elfers senior curator of paintings, Art of Europe, in a press release. “Our hope is to gain a deeper understanding of these works, which were painted during an interesting, transitional, and intense time in the artist’s career.”

According to a press release, the two portraits have not been restored in about 50 years. The paint surfaces have been marred by old retouching and layers of discolored varnish.

Over the course of a year, Rhona MacBeth, Eijk and Rose-Marie van Otterloo conservator of paintings and head of paintings conservation, will restore the two portraits to a quality closer to their original condition, revealing, according to the press release, the “beauty of Rembrandt’s brushwork.”

The MFA’s curators and conservators had discussed restoring the paintings for about a decade prior to the start of the project, but at a museum as large as the MFA there are many pieces that demand more immediate attention.

“They weren’t a burning priority,” MacBeth said. “There are certain things where we really feel we can’t put them on view without doing some work there—they don’t really represent what the artist intended.”

The Rembrandt paintings never achieved high-priority status because they look relatively well-preserved in the MFA’s galleries.

“With the Rembrandts it’s pretty interesting because they look pretty good in the galleries,” MacBeth said. “We have beautiful galleries with beautiful light. They don’t look bad, but we always knew they could look better.”

Funding for the restoration was another obstacle the museum had to overcome in order to initiate the project. The MFA approached The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF) with the idea of a partnership to fund the restoration of the companion paintings. The Portrait of a Woman with a Gold Chain’s treatment is funded by a grant from TEFAF, and the MFA is committed to restoring Portrait of a Man Wearing a Black Hat in turn.

“We would never treat one portrait,” MacBeth said. “They have to stay in balance.”

The curators and conservators work closely to determine when it is the best time to begin an extensive restoration, prioritizing pieces based on their conditions and upcoming inclusion in installations and exhibitions.

“Within [the curators’] areas they have priorities, but it’s very much a dialogue,” MacBeth said. “We’re talking to them about which artworks could really benefit from conservation, and they’re thinking about what’s more important.”

Incentivized by the TEFAF grant and the fact that there are many other paintings of equal interest up in the galleries at the moment, the curators decided this year is an ideal time to restore the pieces. After making the decision, interest in putting the pieces in the “conservation in action” space developed. MacBeth attributed this interest in part to the universal appeal of Rembrandt and fascination with the way in which he painted.

“I think the kind of intimacy of seeing them off the wall, out of their frames, people interacting and touching them, and also trying to explain to people what I’m seeing, I think there’s a lot of interest in that,” she explained.

Originating somewhat incidentally over a decade ago, “conservation in action” has become a highly popular program at the MFA. The conservators were working on a project too large to fit into their typical studio and were forced to close a gallery to complete the restoration. They were approached with a request for the gallery to have a window so that the public could view the process, and an overwhelming positive reaction made the program permanent.

None of the conservators work in the “conservation in action” studio full-time, but rather they rotate through at different times of the week, interacting with the public and answering questions when present. Large-scale projects are typically those placed in the “conservation in action” space, but smaller pieces like the Rembrandts can be featured as well.

“It seems like there’s just a great deal of interest in—I think it’s a modern age phenomenon—seeing behind the scenes,” said MacBeth. “We really wanted to try and make some of the things that happen out of sight more front-of-house.”

Although the Rembrandt paintings will be taken out of the “conservation in action” space at the end of February, MacBeth said they may return at a different stage of the restoration.

“It’s just a different way of understanding and interacting and perhaps sort of giving a different way of looking into art,” she said.

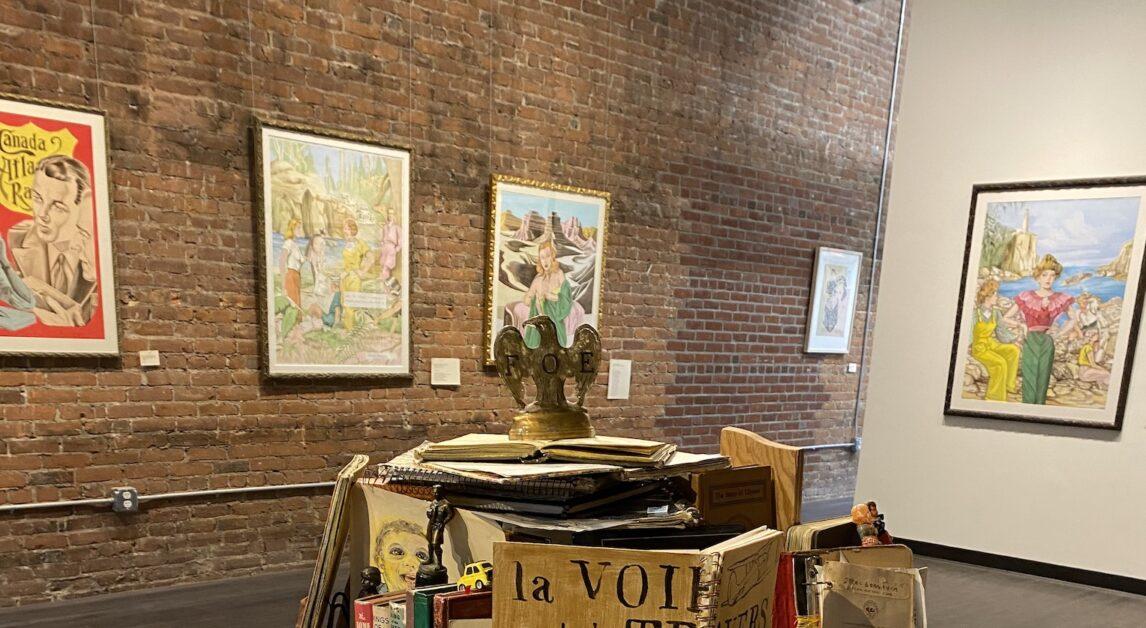

Featured Image by Alex Gaynor / Heights Editor