Malcolm Langford, a professor of public law at the University of Oslo, emphasized the importance of considering human rights frameworks besides the United Nations international human rights regime.

“If you want to understand the future development of economic and social rights, we need to see these other currents of thought, because like any field, it’s constantly moving, and if we don’t look at the yang of the yin—what’s the other side—we will be missing out on what’s coming along,” Langford said.

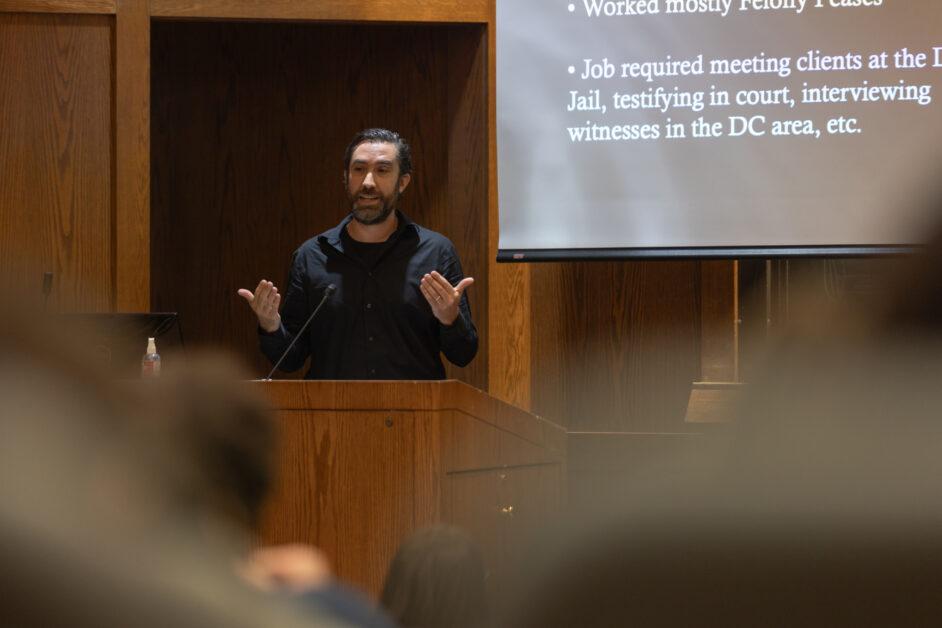

Langford was one of five panel members who spoke on Oct. 2 as part of a discussion hosted by the Center for Human Rights and International Justice on The Oxford Handbook of Economic and Social Rights. He is a co-editor of the handbook, along with Katharine Young, a law professor and associate dean for faculty and global programs at Boston College Law School.

According to Young, the handbook is an ongoing project in which contributors from various disciplines provide their perspective on different historical, economic, or political elements of human rights.

“Many disciplines outside of law have had a lot to say, and yet have often written and published in separate streams,” Young said. “Our Oxford Handbook is a real attempt at an interdisciplinary collaboration and broadening of this field.”

Balakrishnan Rajagopal, UN special rapporteur on the right to housing and associate professor of law and development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, discussed the effects of the stay at home orders during COVID-19 on those who do not have access to housing and clean water.

“It actually was a moment when governments around the world suddenly realized that people having access to water and homes, which are safe, is a critically important thing,” Rajagopal said.

To address the problem of adequate housing, Rajagopal said governments need to implement human rights policies with long-term agendas.

“Because I was getting information from states and other actors about all these temporary measures, I said, ‘Look, don’t just treat it as a temporary thing because we have to actually see the moment and see where the more permanent changes can happen,’” Rajagopal said.

According to Rajagopal, governments tend to focus on bigger projects that have a hard time getting started. To combat this issue, Rajagopal explained that governments must consider the more cost-effective and beneficial alternative practices that benefit underserved communities.

“Government loves mega projects, and that’s what they want to approve,” Rajagopal said. “And no matter what alternative practices you actually put forward—I’ve seen over 20 years many communities who actually put forward extremely viable alternative projects—they just don’t get off the ground.”

Sam Bookman, a candidate of the doctor of juridical science program and graduate teaching fellow at Harvard Law School, highlighted the value of taking on different perspectives to fully understand and address human rights, including environmental rights.

“If we’re going to find a way forward in our own understanding and evaluation of economic and social rights, including their environmental dimensions and linkages, we need to understand that rights can include a range of sources, ambitions, practices, and futures,” Bookman said.

Lucie White, the Louis A. Horvitz Professor of Law at Harvard Law, recounted her experiences working in Ghana and proposed a four-part solution to remedying the country’s debt crisis—a crisis that prevents children from securing their right to education, she said.

“First, name the problem as one of the most significant human rights injustices of the post war era,” White said. “Second, map in detail how it works. Third, link up with academics and activists who are actively working in this area. Finally, make global human rights forgiveness a human rights priority.”

With many different human rights issues and movements across the globe, Young said that it is crucial to address human rights through a pluralist lens.

“It’s not all taking place in one space—these are plural spaces and plural practices,” Young said. “There are plural futures at stake.”