Since returning to campus in the fall, Boston College students have grown accustomed to COVID-19 testing, social distancing, and contact tracing. These new measures have created a unique BC experience, but changes to college life are all too familiar to students throughout the Boston area.

While UMass Amherst freshman Anna Cincotta slept in her dorm on Feb. 7, an email sat in her inbox. After being on campus for only two weeks, Cincotta read in the email that students would be required to “self-sequester” in their rooms for a minimum of 14 days, or until public health conditions at the school improved substantially.

“It was just like ‘this is not a good sign for the semester,’” Cincotta said.

The university reported 298 positive tests, bringing the total number of active cases up to 398, in the two days leading up to the decision.

Students living both on campus and off campus were directed to remain in their rooms, following consultation with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, according to the email. Students were told to leave their rooms only to get meals, attend twice weekly COVID-19 testing, and for medical appointments.

Cincotta said the email communications from UMass were unclear about the specific guidelines and that the university did not strictly enforce the lockdown.

“The lockdown definitely helped,” Cincotta said. “I don’t know if everyone followed it. Because there’s just very little enforcing going on.”

Students that failed to comply with the guidelines would be subject to disciplinary action, including removal from the residence halls or suspension, according to the email.

UMass freshman Jessica Galego felt like she had a fair warning that a lockdown was imminent, since she regularly checks the school’s COVID-19 dashboard and noticed cases rising.

“Everybody was definitely frustrated about it because we weren’t sure if it would end up getting extended or kind of what was going on,” Galego said. “Just like simple things like not being able to do our homework in the lobby was really frustrating.”

Following the two week lockdown, Cincotta was contact traced by University Health Services, sending her back into quarantine. Cincotta chose to quarantine at home because she thought it would be more comfortable than university quarantine housing.

Both Cincotta and Galego said that students were not provided transportation to on-campus quarantine housing, making it challenging to walk across the campus with the belongings they were bringing with them into quarantine.

“They’ve told kids just to walk there by themselves and that they can’t provide any transportation, so they were definitely lacking in that aspect,” Galego said.

Boston University freshman Jami Hamman shared a similar fate as Cincotta—a 10-day quarantine.

While in on-campus quarantine housing, Hamman said BU also provided mental health check-ins for students in quarantine, which she said reflects BU’s genuine care for the well-being of its students.

BU provides meals, grocery delivery, and weekly laundry services at its Charles River Campus and Fenway Campus quarantine locations, according to BU’s website.

“I could call anybody anytime I wanted and I could special request items. I could special request, like, comfort food or I could special request lotion, I don’t know, random things …,” Hamman said.

Tufts University also provides on-campus quarantine housing in modular residential housing that it built specifically for quarantine and isolation, according to Tufts’ website. Sophomores Elsie Schaubeck and Gillis Linde agreed that their school is doing a good job of contact tracing and providing resources for quarantine.

Tufts freshman Vicki Tran said that the contact tracing system at her school is inconsistent. After learning that a girl on her floor tested positive, she was surprised when she was not contact traced, since her floor has a communal bathroom.

Northeastern houses students in quarantine or isolation in COVID-19 Wellness Housing and provides both regular meals and check-in calls from the school’s COVID-19 wellness team, according to the university’s website.

“I think with quarantine, it’s as best as it can be,” Molly Foster, a sophomore at Northeastern, said. “They give you housing, they give you food. You know, I haven’t heard too many problems with the food or the housing. So it seems good.”

One positive test can land a student in isolation, whether in a hotel, mods, or on-campus housing, but after contact tracing, one test could put several others into quarantine. In order to help mitigate the spread of the virus, Boston schools have implemented varying measures of asymptomatic surveillance testing.

Both Tufts and UMass test students twice a week, while Northeastern and BU test students three times a week.

Tufts tested students every other day until March 1 when the university decreased its testing to twice a week.

“I really like the testing policy,” Linde said. “It’s really easy, like, you’re in and out within like less than 5 minutes, so it’s pretty quick and I think it’s safe.”

Tufts’ response to students who miss their tests is to send them an email, according to Tran. She said that this lack of enforcement and the reduction in testing makes her feel unsafe on campus. The student affairs staff will ensure student accountability if there is a pattern of missed tests, according to Tuft’s website.

“Before, we got tested every other day and so like if you missed your testing you would get an email but that would be it,” Tran said. “You wouldn’t be, like, punished or anything … That doesn’t really make people scared to go to testing, kind of, so I know people that miss it often.”

At Northeastern, Foster feels that the amount of testing allows her and her peers to feel comfortable on campus.

“I think it provides a lot of security …,” Foster said. “And I know everyone [I’ve] been interacting with in classes and, like, in my dorm, is also being tested that frequently. So it gives a lot of peace of mind.”

Living on a floor with a communal bathroom, BU freshman Kim de la Rosa also said she feels safer knowing she is around others who are getting tested regularly.

“I feel good,” de la Rosa said. “Honestly, I think we’re getting tested more than most colleges around, and it makes me feel a lot safer, especially when it comes to, like, being able to see friends and stuff like that.”

The dean of students at BU sends a warning email to students who fail to comply with the three times per week testing policy, saying their Wi-Fi will be disconnected and their Terrier Card will be disabled unless they complete a rescheduled test, according BU’s website.

To promote compliance with COVID-19 guidelines, BU partners with a student-run campaign called F*ck It Won’t Cut It. Following the campaign’s launch in August, Hamman said, it was unclear to students on campus whether the campaign was run by students or the university. Colin Riley, the executive director of public relations at BU, said the campaign is “by students, for students,” in an email to The Heights.

Hailey McKee, a BU graduate and a public relations manager for the campaign, said that while the organization is separate, the university reached out to students in the public relations lab to create a campaign that would resonate with the student body.

“Students like the idea that it felt like a friend sort of calling them out, someone that could hold them accountable,” McKee said. “So, with that in mind, we came to the university and they really put faith in us and trusted us that we knew what our fellow students wanted to hear, and what would really resonate with them.”

The promotion on Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter of the campaign made it more relatable, according to McKee. Hamman and de la Rosa agreed that the campaign has made an impression on the COVID-19 culture at BU.

Along with testing, BU requires students to complete a daily symptom check in order to enter buildings on campus. Failure to complete the daily symptom check will result in the same consequences as testing noncompliance.

“I feel like it’s just a good reminder, I think, especially when it’s just a check in, you’re like ‘Oh, I can’t taste today, I guess I have COVID,’” Hamman said.

Despite the requirement, de la Rosa is unsure of the daily check’s effectiveness, and said that students have memorized the questions, responding quickly without much thought.

“I appreciate the effort, I’m just not sure how effective it is anymore because people are just going to answer ‘no’ to everything,” de la Rosa said.

Tufts also asks its students to complete a daily four-question survey screening for COVID-19 symptoms to enter buildings on campus, according to the Tufts website.

“They’re not monitoring it as carefully as the testing,” Schaubeck said. “If you miss testing they’ll send you an email or something, but with the symptoms monitoring, I haven’t done it in a while.”

At Northeastern, Foster and sophomore Isabelle Brandicourt agreed that logging their symptoms on the Daily Wellness Check before coming to campus, which the university requires, is not very useful.

“I mean, it’s a good reminder,” Brandicourt said. “But at this point, I feel like we all know what the symptoms are.”

This quasi-dystopian reality brought on by the pandemic has distorted the college experience, altering the classroom experience and social scenes.

Most students continue to attend a mixture of in-person and online classes during the spring semester. At Tufts, Linde has two in-person classes out of the five he is taking, while Tran has one hybrid class with the remainder online.

The combination of in-person, hybrid, and online classes at BU can get confusing, Hamman said.

“It’s complicated … It’s like, my one class, it’s on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and then we meet in person every second Tuesday, so like once every two weeks,” Hamman said. “And then one discussion section every week.”

As a pre-med student at UMass, Cincotta said her virtual classes have not been as demanding as in-person ones were, but feels she is missing out on the hands-on experience of chemistry lab.

“We’re not getting that experience vital in the field of medicine, so we’re kind of missing out,” Cincotta said. “And it’s going to be a little patchy, trying to restore what we don’t know, next semester or sophomore year.”

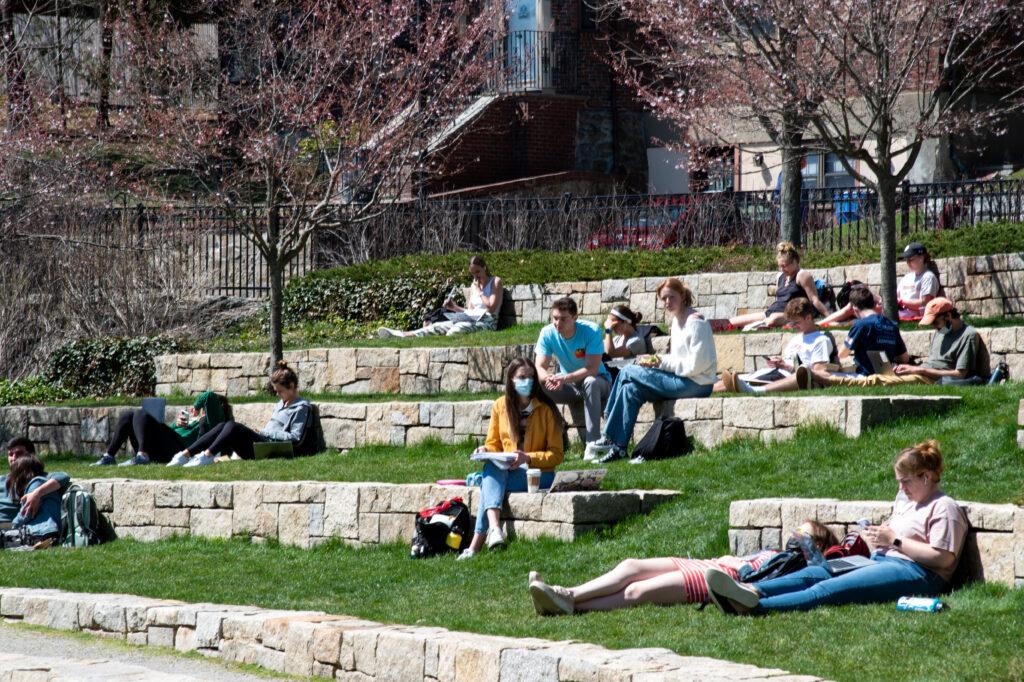

With many online classes and club meetings held over Zoom, residential life and dining halls serve as main sources of in-person interaction.

Tufts instituted a residential cohort system in the fall semester, organizing students living on campus into groups of six to 12 students. Following consultation with students, residential staff, and the university’s medical team, the university discontinued the system in the spring semester.

“Although the cohort thing is not official now, I think it was an amazing system,” Linde said. “It was really good because it made you less isolated because you’re with a bunch of friends.”

Tufts acknowledged that there are benefits and risks to this model. While the model promotes peer accountability, the university’s website states that spending time with others without physical distancing increases the risk of spreading COVID-19.

“I think the issue is that since they already allowed them last semester, like, we’re not technically in a cohort but we’re still end up doing things with the same people anyways,” Schaubeck said. “So I don’t really think it has affected people too much, because I think in both cases people were still being careful.”

Similarly, at the beginning of the academic year, BU instituted a household system made up of a student in a single, two students in a double, suitemates, or a group of students on the same floor that share a common bathroom, according to BU’s website.

BU also asks students who are on floors with shared bathrooms to develop daily schedules for bathroom use with those in their household to minimize exposure.

While well intentioned, de la Rosa said, the household system did not help her find friends.

The university allowed households to eat together in the dining halls at designated tables until early February. Now students can eat at single-occupancy tables in the dining halls. Working in the dining hall, de la Rosa said that she has noticed people are less likely to follow rules when they are eating with friends.

Tufts, on the other hand, has eased its dining restrictions, allowing students to reserve a table in the dining hall. During the fall semester, students were only allowed to take-out food using a mobile ordering app.

“I think it isn’t bad, like you can usually get a reservation within five minutes, so it kind of organizes things,” Schaubeck said.

To facilitate the social scene on campus, Northeastern has added dozens of firepits, propane heaters, and outdoor dining tents to provide students with a safe way to socialize, according to its website.

Each tent throughout campus has a specific decoration theme meant to make the tents welcoming, according to Joseph Aoun, the president of the university. Some of the themes include a bamboo garden, a rainbow room with multi-colored umbrellas, and a Renaissance ballroom including replicas of works by Michelangelo and Raphael.

Brandicourt said that students frequently use the tents and that they are a great way to see friends in a safe way. Foster says that she uses the tents as a place to do homework, study, and hang out with friends.

“But they do close at 10, so it’s a little bit frustrating when you’re trying to hang out with friends on like a Saturday or something and you don’t want to break the rules, and you also are getting kicked out of the heated spaces,” Brandicourt said.

Students from Northeastern and BU agreed that fraternity activity likely contributes to the spread of COVID-19.

Brandicourt said that there have been scares of outbreaks within fraternities at Northeastern, particularly during pledge season, but said that the majority of those in attendance are fraternity brothers.

“There’s stuff still happening, but I would also say that the people that are involved in that are just the frat members like, they’re not reaching out to people outside of the frats,” Brandicourt said.

Both schools have cracked down on Greek life and party culture. BU suspended 12 students in October after they were caught going to at least one out of three off-campus parties, and Northeastern dismissed 11 freshmen found together in a room at the Westin Hotel in early September.

Hamman said there are still “under the table” off-campus parties at BU that the university is not aware of, but the university has been strict with the number of people found together in on-campus rooms.

“They’ve tried to make it a point that if you break the rules and put other people at risk that it’s not tolerated and people have really been listening,” Hamman said.

At UMass Amherst, Greek life comprises one of the largest organizations on campus. Students said that UMass Amherst has not consistently enforced gathering limits for their fraternities.

“There are also definitely a ton of people who don’t really care about the pandemic, and have been going to giant frat parties or off-campus parties,” Galego said. “So definitely, like a mix of people who care and people who do not care about the pandemic.”

The fraternity Theta Chi threw two back-to-back parties to start off the spring semester on Jan. 29 and Jan. 30 resulting in an interim suspension for the frat, according to The Massachusetts Daily Collegian.

“There are those people that choose to risk it and choose to gather and make poor decisions and then you can just avoid those people,” Cincotta said. “I think it’s kind of your choice whether you want to be safe or risk it.”

Cincotta said a petition has been circulating among students to encourage UMass Amherst to disband Theta Chi.

Between Jan. 1 and Feb. 5, 345 students were referred to the UMass Amherst Student Conduct office for violations including room capacity, social distancing, face coverings, noise, guest policies, failure to comply with contact tracing, and failure to comply with federal, state, and local COVID-19 guidelines. The university-imposed sanctions include suspension, removal from on-campus housing probation, and reprimanding, according to an Amherst Town Council meeting.

At Northeastern, Foster said, students generally follow the rules, because they know that’s what they have to do to stay on campus.

“I think everyone’s starting to get tired of it, but we know … we all have to do our part,” Foster said. “A lot of people wish that we could have people in our dorms and hang out more, and that we could go to all of our classes in person and have a little bit more normality. But, … as much as it stinks, everyone knows … if we keep being smart about it, things will get better.”

Across the Boston schools, this sentiment seems to strike a chord: Students are willing to do what it takes in order to have some semblance of normalcy.

“I think people at this point just want things to be over and better,” Schaubeck said. “I’ve talked with a bunch of people about what they think [fall 2021] will be like, and at this point we feel like if they still have us, like wear masks … [and] maybe some social distancing, like at that point, we’d be fine. So, I think we’re kind of willing to do anything to make things resemble normalcy.”

Featured Image Courtesy of Garrit Strengthe

Photos Courtesy of Garrit Strengthe and Elsie Shaubeck