Hate speech has an important role to play in society, and it would be unwise to ban it on college campuses, according to Harvey Silverglate, a civil liberties attorney and co-founder of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE).

“You want to know who the people are who harbor these absurd notions,” Silverglate said.

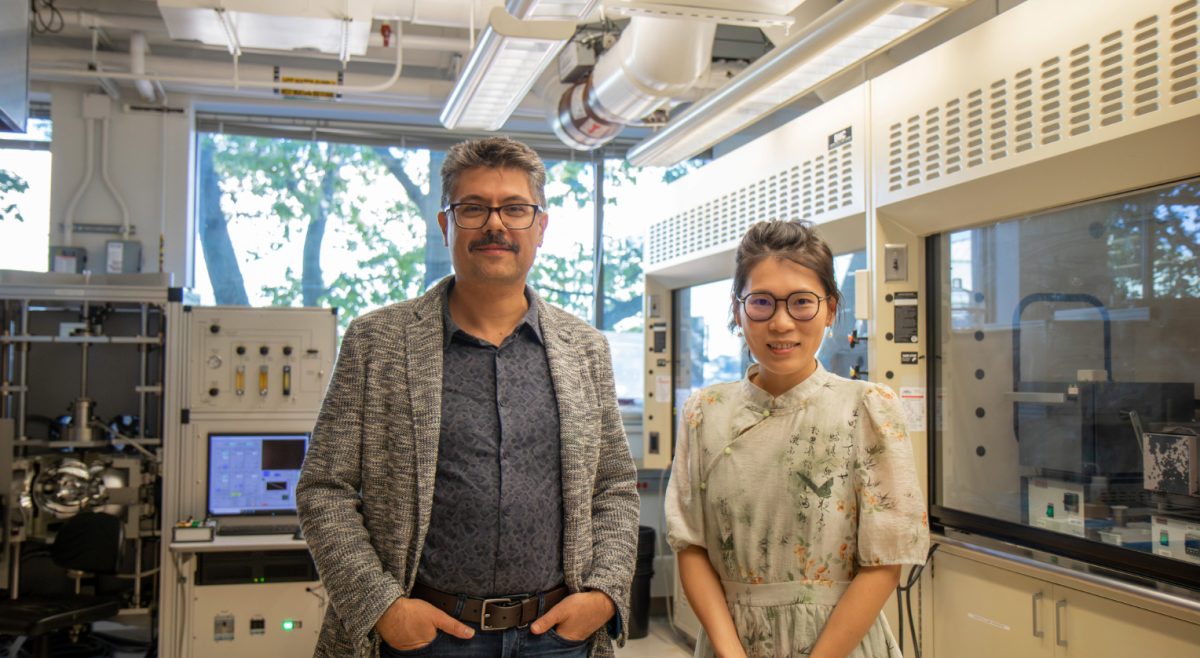

Silverglate joined Boston College Law Professor Kent Greenfield, a leading expert in constitutional law and the Thomas F. Carney distinguished scholar at BC Law, on Thursday afternoon for a debate on the role and limits of free speech on college campuses.

Opposing Silverglate’s view on hate speech, Greenfield argued that college campuses are bastions in pursuit of truth and need to become communities where everyone feels safe to contribute to that journey.

“Universities are communities of learning and education,” Greenfield said. “And much like you don’t want to have a hostile work environment because it makes people not be able to achieve what they can in the workplace, hostile learning environments have effects on learning as well.”

The debate had a conversational, friendly tone throughout, with room left for dissent and humor. Topics ranged from hate speech and through what means, if any, it is punishable, to the responsibility that university administrators have to protect their students’ positions.

Silverglate staked his position as a free speech absolutist, arguing that hate speech should be protected as a revelatory device to the opinions of your peers.

“I can figure out who loves me, but it’s very useful to find out who hates me,” Silverglate said.

Greenfield considered himself a communitarian, valuing safe environments where vitriolic opinions are filtered out for the betterment of the academic society.

“When I’m teaching Con Law, I’m not really seeking truth because we’re not researching it or experimenting,” Greenfield said. “We’re educating, we’re talking as a community, and I think there’s some kinds of speech that is inconsistent, or could be inconsistent with that purpose.”

Greenfield cited a free speech case study on the expulsion of two fraternity members at the University of Oklahoma in 2015 after they led a racist chant.

“The First Amendment is too broad,” Greenfield said. “I don’t think the search for truth is furthered by protecting somebody singing about lynching.”

Silverglate asserted that these sentiments don’t disappear through condemnation and instead should be protected to determine who harbors abhorrent opinions.

“It’s an unpleasant subject in American history—very unpleasant subject—but you want to know who the racists are,” Silverglate said. “You don’t want to prohibit people from disclosing that they’re racists.”

One student asked about how universities should approach punishing students who espouse hate speech and how that role can be balanced with preserving freedom of speech.

In response, Silverglate expressed sympathy for students who are personally frustrated by offensive speech. Still, he maintained that even if students chose to speak up, universities have a duty to be mindful of the power they wield.

“It is not the university’s position to be the arbiter of what speech is more socially useful and what is not,” Silverglate said.

Greenfield, on the other hand, argued that universities also have a right to promote their institutional values.

“Brandeis doesn’t have to invite a Holocaust denier to come speak at Brandeis,” Greenfield said. “I think where we differ is that there is some role for universities to say these things, that there are principles we hold dear.”

Another student question referenced the latest FIRE Free Speech rankings—in which BC ranked No. 251 out of 257 universities—and how BC could foster a better atmosphere for free speech.

Silverglate responded initially by voicing frustrations with his alma mater, Harvard, before stating that “all hate speech code should be abolished immediately,” and that “if we would get rid of 80 percent of the [university] administrators, a lot of these problems would disappear.”

Greenfield noted that he and other faculty members at BC Law are currently writing a new academic freedom policy, affirming that a major shift is essential to push against censorship on college campuses, while also defending BC’s existing policies.

“We have a harassment code here at BC for if a professor is harassing people with just words, and I think that is completely appropriate that harassment can be done completely with words,” Greenfield said. “It’s not just whether it’s a hate speech code or not. I think there’s a line to be drawn.”

Silverglate tied his views back to diversity in the United States, saying that everyone, regardless of their background or stance, should be able to state their positions safely without government repercussions.

“You have to make provisions for the people with minority opinions, with unpopular opinions, who express their views,” Silverglate said. “The obligation of the institution is to provide security.”