Indy, a Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever, sits in the passenger seat as his person, Todd (Shane Jensen), drives away from the city toward a large, isolated house in the woods. Once there, his ears occasionally perk, registering sounds and scents his human companion cannot—both natural and supernatural.

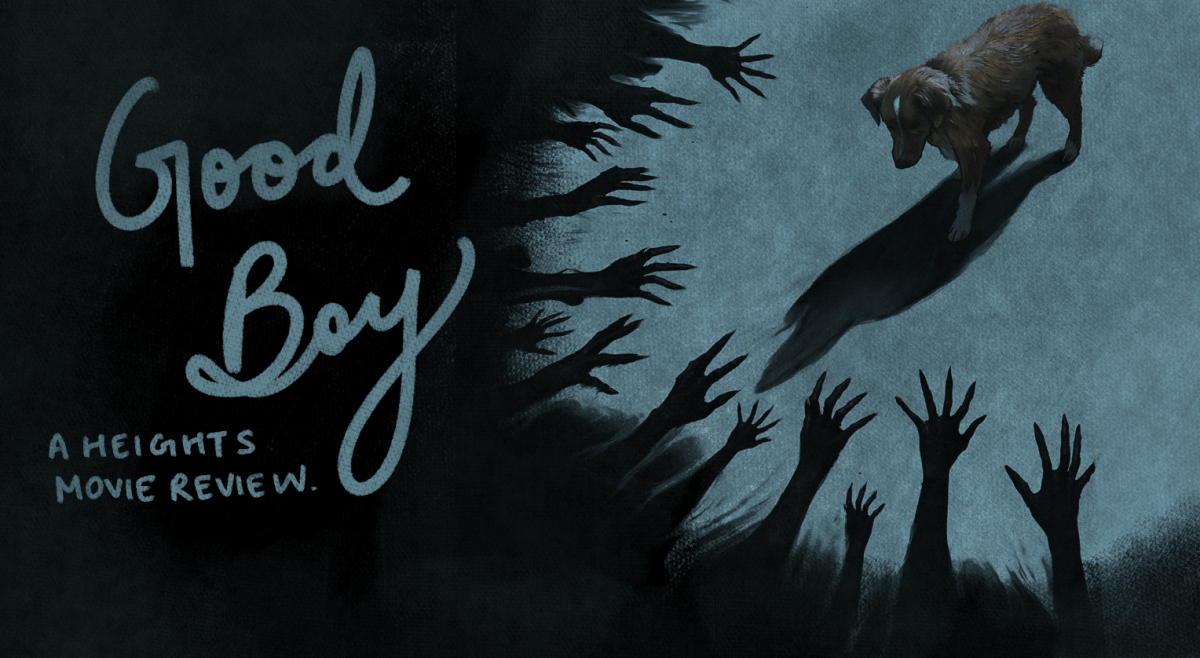

Ben Leonberg’s 2025 feature directorial debut, Good Boy, takes on the high-concept premise of a haunted house film told entirely from a dog’s perspective. It follows Indy and Todd, a young man relocating due to a worsening chronic illness, as they settle into Todd’s late grandfather’s eerie, vacant home.

The film quickly establishes the dog as the audience’s sensory guide, the only one aware that a malevolent presence is already settled in.

Good Boy, which received significant praise and awards for its central canine performance, like the inaugural “Howl of Fame” award at the SXSW Film & TV Festival Awards, is a unique blend of supernatural horror and interspecies devotion.

Todd’s life is defined by his declining health, forcing him into the isolation of the rural house despite warnings from his sister, Vera (Arielle Friedman), who fears the location is haunted and contributed to their grandfather’s death.

Early scenes are expertly filmed from Indy’s low-to-the-ground perspective, framing Todd and the environment in a way that emphasizes the dog’s role as the central observer. Indy immediately senses a presence at the house, the supernatural being often manifesting as subtle shadows.

The film’s greatest triumph lies in the genuine nature of Indy’s performance. The dog, Leonberg’s own pet, conveys complex emotions through natural reactions, requiring no CGI or human voiceover.

Leonberg masterfully directs the horror through simple juxtaposition: a neutral look from the dog followed by a shot of an empty, dark corner or a flicker of a skeletal figure. This technique forces the audience to project fear and understanding onto the dog, creating an immersive, sensory-driven form of tension that few horror films achieve.

The opening minutes, where Indy’s hackles rise or he follows an unsettling scent, immediately anchor the audience in an urgent sense of dread.

Several characters are introduced within the first quarter of the runtime. Indy and Todd encounter Richard (Stuart Rudin), a longtime neighbor who found Todd’s grandfather after his death and warns them about fox traps in the woods.

Richard also mentions the grandfather’s own missing dog, Bandit (Max). Indy later encounters an apparition of Bandit inside the house, who guides him toward a clue about the home’s dark history. These interactions serve as necessary world-building, but like many of the film’s human figures, they feel purposefully peripheral, designed only to advance the canine-centric mystery.

While Indy demonstrates extraordinary loyalty and instinctual intelligence, the human narrative feels less developed. Todd’s quick descent into frustration and aggression as his illness progresses is necessary to push the plot forward and isolate Indy, but this element of the story is the least convincing.

The script, co-written by Leonberg and Alex Cannon, seems more interested in how the dog reacts to the horror than in the human emotional consequences of the haunting. The movie is self-aware in its focus, consistently obscuring Todd’s face or framing him only from the torso down, underscoring that the human is not the point of view that matters.

The film is darkly ironic, positioning the dog as the competent, emotionally stable protector in a situation where the human is hopelessly out of his depth. Indy ceaselessly investigates the source of the evil, whether it be in the form of slamming doors or visions of the entity, showing a loyalty that endures even as Todd’s health and temperament deteriorate. Indy is constantly attempting to communicate the peril, revealing that he is ready to take on the burden of saving his companion.

The movie is distinct from other haunted house films because its horror is rooted in vulnerability and helplessness. The claustrophobic setting—the isolated house—is intensified by Indy’s perspective, making every shadow and creak feel monumental. The emotional core is the fear of loss, as his person’s safety is the only thing that truly matters to Indy.

Good Boy possesses a clear, goal-driven narrative that manages to transcend its simple premise. The film’s short runtime, 73 minutes, is a wise choice, utilizing its single, powerful idea to maximum effect. The otherwise restrained score and sound design are elevated during pivotal moments of fear or devotion, emphasizing the sincerity of the central relationship.

Ultimately, Good Boy finds its strength as a deeply moving testament to the fidelity of a dog. Though it meets the criteria of originality in its concept and technical execution, its narrative feels restricted, at times relying on familiar tropes that are only elevated by its non-human star.