Since Antonin Scalia died, the Supreme Court hasn’t been the same.

Now, because of the even split among the justices—four liberals, four conservatives—the court hears fewer cases, and even fewer controversial ones. Naturally, justices don’t want to waste resources on trials that will most likely end in voting deadlocks. What’s more, they are not expected to increase their workload in the new term because it is unlikely a ninth justice is confirmed by the Senate anytime soon.

On Monday, they met to discuss adding more suits for the upcoming term. Among stacks of hot-button issues like Obamacare, the transgender bathroom law, the Washington Redskins’ trademarks, and President Obama’s ability to fill the vacant Supreme Court seat without Senate approval, one nonpartisan case may find its way to the top: amateurism in college sports.

O’Bannon v. NCAA concerns student-athletes’ right to publicity and the NCAA’s antitrust violations. O’Bannon’s lawyers argue that by capping player compensation at scholarships and preventing athletes from profiting off of their name, image, and likeness (NIL), the organization restricts trade and limits market competition. When it was brought to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, the judges agreed. In their decision, however, they reversed a lower court’s ruling that allowed schools to place $5,000 per year into a trust for men’s basketball and football players to access upon exhaustion of their eligibility.

So who won? Well, both, and at the same time, neither.

Two federal courts ruled in favor of O’Bannon, essentially saying that the NCAA and its member schools sold their athletes’ NIL to companies for profit without their consent. But the Ninth Circuit also upheld the longstanding tradition of amateurism—the idea that players should not be paid in order to preserve the student-first, athlete-second illusion. The latest ruling put the matter in limbo by banning schools from compensating athletes above the full cost of attendance, but also conceding that the NCAA’s current market limits are a restraint of trade.

That’s why both sides agree on one thing: they want the case heard again. The NCAA expects Round Three to echo the Ninth Circuit’s view on amateurism and result in repeals of antitrust violations. Meanwhile, O’Bannon hopes the Supreme Court will side with Ninth Circuit Chief Justice Sidney Thomas, who criticized the court’s outdated majority decision to preserve amateurism.

“The NCAA insists that this multibillion-dollar industry would be lost if the teenagers and young adults who play for these college teams earn one dollar above their cost of school attendance,” he wrote in his dissent. “That is a difficult argument to swallow.”

In an age when the highest-paid public employee in 39 states is a college football or men’s basketball coach, and the NCAA is raking in $1 billion annually for March Madness TV deals, it’s hard to argue with Thomas. Yet the NCAA thinks that a Supreme Court case could put the issue of amateurism to bed once and for all. Specifically, the defendants will cite a 1984 ruling that said paying college athletes would taint the NCAA’s product.

If I were in NCAA President Mark Emmert’s shoes, I would be wishing for the Supreme Court to include the lawsuit on the docket for the new term, which is expected to be announced today. Most would be shocked if it made the final cut in a pool of thousands of petitions. But if it did, the NCAA would have a chance, clinging to a 32-year-old decision that predated our commercialized era, of keeping cash out of college sports. Frankly, it might be one of the last shots to affirm its definition of amateurism.

The NCAA faces an onslaught of other legal battles even if O’Bannon is put to rest by the Supreme Court this week. In the event that the justices reject O’Bannon’s petition, all eyes will turn to prominent sports labor attorney Jeffrey Kessler and the Jenkins case. Kessler and his legal team are leading another antitrust charge in Northern California—with the same judge that produced the favorable ruling for O’Bannon in his District Court trial—that aims to fundamentally change the way college athletes are treated in the system.

Kessler’s colleague, Joseph Litman, told me that he doesn’t think the NCAA should be exempt from the rules of a free market.

“If we were to win the case, we believe that conferences, individually, would be allowed to make their own choices about compensation level for athletes,” Litman said. “And that there would be the opportunity for the individual schools and conferences to make those choices in a market, which is the same as any other kind of market in the antitrust law they’re employing, to protect that kind of competition.”

The Jenkins case has the potential to make an even larger impact on the NCAA than O’Bannon. If O’Bannon is accepted by the Supreme Court and the justices grant college athletes publicity rights, then the NCAA wouldn’t be able to block a $5,000 stipend awarded to players upon graduation. The association’s current policies, though, would remain enforced when it comes to student-athletes and their NIL rights (or lack thereof) to sign autographs, sell jerseys, and profit off of their image like other public figures.

But if Kessler and Litman are able to eke out a win for the plaintiffs in the Jenkins case, players could theoretically unionize and negotiate for their own compensation. And while schools and conferences would have autonomy over their individual systems, a laissez-faire market could emerge where universities compete to offer the best educational advantages, health benefits, and—possibly—cash incentives for athletes to join their programs.

At first, I was excited by the prospect of such a system. Scholarships seem a lot like compensation for work, so treating football and men’s basketball players as employees doesn’t sound unreasonable.

But then I spoke with the Deputy Athletic Director at Stanford University, Patrick Dunkley, about the possible implications of the Jenkins case.

“If the Jenkins case were to be found in favor of the plaintiff, it would completely disrupt the model that allows for broader-based sports programs at most institutions,” Dunkley said. “It would be very difficult for an institution to pay an open-market salary for student-athletes for football and men’s basketball and also maintain their other sports offerings. In order to be a Division I program, you have to have 16 sports. So you have to have some way of funding those other 14 sports. It would definitely create a funding challenge for all schools, and a funding challenge that may be insurmountable for most schools.”

For this reason, Dunkley would prefer for the debates over amateurism and antitrust violations to be settled by the Supreme Court in the O’Bannon case instead. But, even then, it would depend on the specific wording of the ruling.

“If the Supreme Court were to say that the limits on student-athlete compensation set by Judge Wilkins at the trial court level were somehow an antitrust violation—and therefore allowing student-athletes to negotiate for the use of their name, image, and likeness—then I think the O’Bannon case starts to look more like the Jenkins case. And the results and the consequences become very similar,” Dunkley said.

Would a Supreme Court ruling against O’Bannon effectively ruin Kessler’s odds of winning in the Jenkins case? Once again, Dunkley says, that remains to be seen.

“Depending on how an opinion from the Supreme Court is worded, it may or may not leave the door open. There is a possibility that there could be a ruling from the Supreme Court that is worded in such a manner that it would kill the Jenkins case,” Dunkley said.

Do student-athletes deserve publicity rights? Yes. The Olympic Model, under which players could profit from NIL, places no additional financial burden on universities. But should college athletes be paid if it means cutting Division I athletics for large numbers of schools (including prestigious programs like Stanford)? Of course not.

For the NCAA, this is a problem that doesn’t appear to be going away in the near future. Three government entities have designated the organization’s treatment of men’s basketball and football players as exploitative in the last couple years: first, a National Labor Relations Board regional director claimed that, because scholarships count as compensation, Northwestern football players are employees and have the right to unionize; then, both O’Bannon decisions dealt the NCAA a crippling one-two punch to the gut of its seemingly foolproof formula.

The race is on. What the Supreme Court will decide this week is whether it will be a sprint or a marathon.

But sooner or later, it appears, college athletes are going to get their money. Exactly how much, however, could determine the fate of athletic departments across the nation.

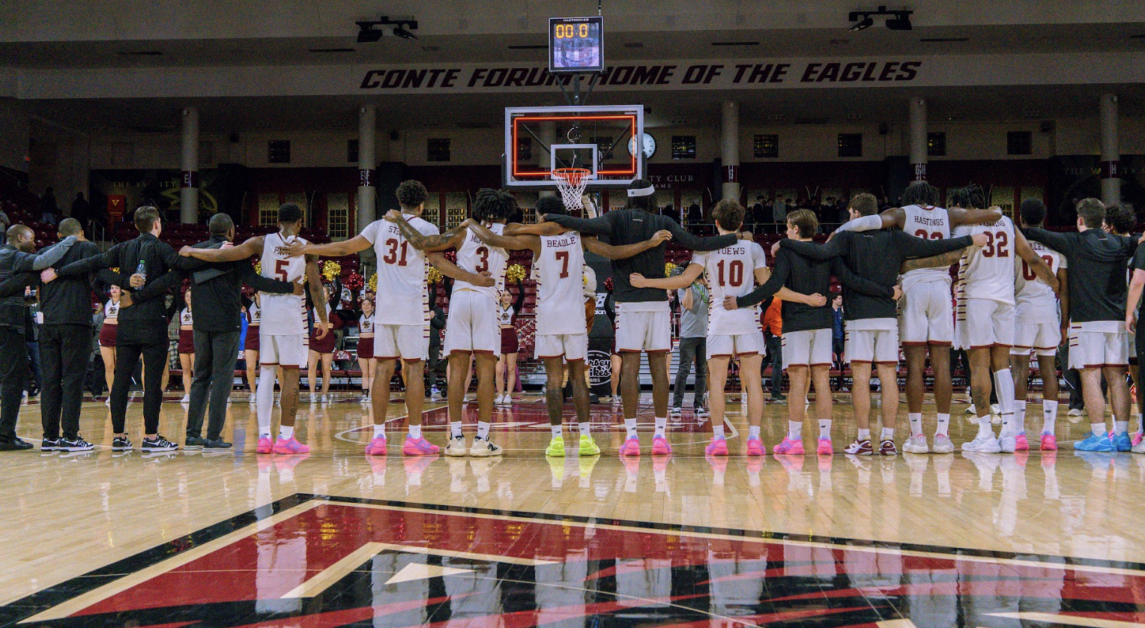

Featured Image by Kelsey McGee / Heights Editor