Physicist Philip Duffy presented a wide array of scientific research and discoveries last Thursday regarding what is widely regarded to be one of the most important issues to college students: climate change.

Duffy is president and director of the Woods Hole Research Center, an award-winning climate change, science, and policy center. From 2011 to 2015, Duffy was a science advisor in the White House, where he had a large influence on both domestic and international climate policy.

Beginning the talk with a historical perspective on the science of climate change, Duffy explained how analyzing air bubbles trapped in ice cores gives scientists a direct archive of Earth’s past climate and atmosphere. These ice cores, which hold hundreds of thousands of years of information, have shown not only a very strong relationship between carbon dioxide (CO2) and temperature, but also rapid change in atmospheric CO2 levels.

“Carbon dioxide is now way outside the bounds of anything that has happened in the last 800,000 years,” Duffy said.

The proposal that greenhouse gasses have an adverse effect on climate is not a new phenomenon—the greenhouse effect itself was discovered and scientifically proven in the beginning of the 19th century, Duffy said.

He then went on to point out some of the manifestations of climate change that are occurring right now. Scientists have observed that both the Greenland Ice Sheet and the Antarctic Ice Sheet are losing mass through satellite imaging. Although it could take centuries, the decay of these two ice sheets holds an enormous potential for sea level rise.

“What could happen is that we can cross a threshold beyond which very substantial melting becomes inevitable,” he said.

Duffy explained how an additional manifestation of climate change can be seen in patterns of recent hurricanes, such as rapid intensification, very high precipitation grades, and slow propagation speeds. Duffy, however, also noted that we do not have an extensive enough historical record of hurricanes—before satellites, most hurricanes went unrecorded—to make a firm statement about their relationship with increasing CO2 levels.

“We are starting to see all of the consequences that we expect from climate change happening in the real world,” Duffy said.

Duffy also emphasized an integral aspect in the discussion of climate change: the difference in warming between developed countries and developing countries.

“In the developing world, temperature change already is very large relative to historic variability,” he said. “In some sense we are experiencing less climate change than the developing world is.”

Next, Duffy outlined what we might expect to see in the future, in terms of consequences and societal impacts of climate change: extreme heat, severe and prolonged droughts, and greater hydrological variability.

Another potentially catastrophic future consequence involves permafrost in the Arctic. Now that the Arctic is warming, the frozen permafrost—ground which holds massive amounts of undecayed organic matter—is beginning to thaw, emitting large amounts of carbon dioxide and sometimes methane.

“There is an awful lot of carbon in permafrost,” Duffy said. “Fifteen hundred billion tons of carbon in permafrost, which is about twice what’s already in the atmosphere.”

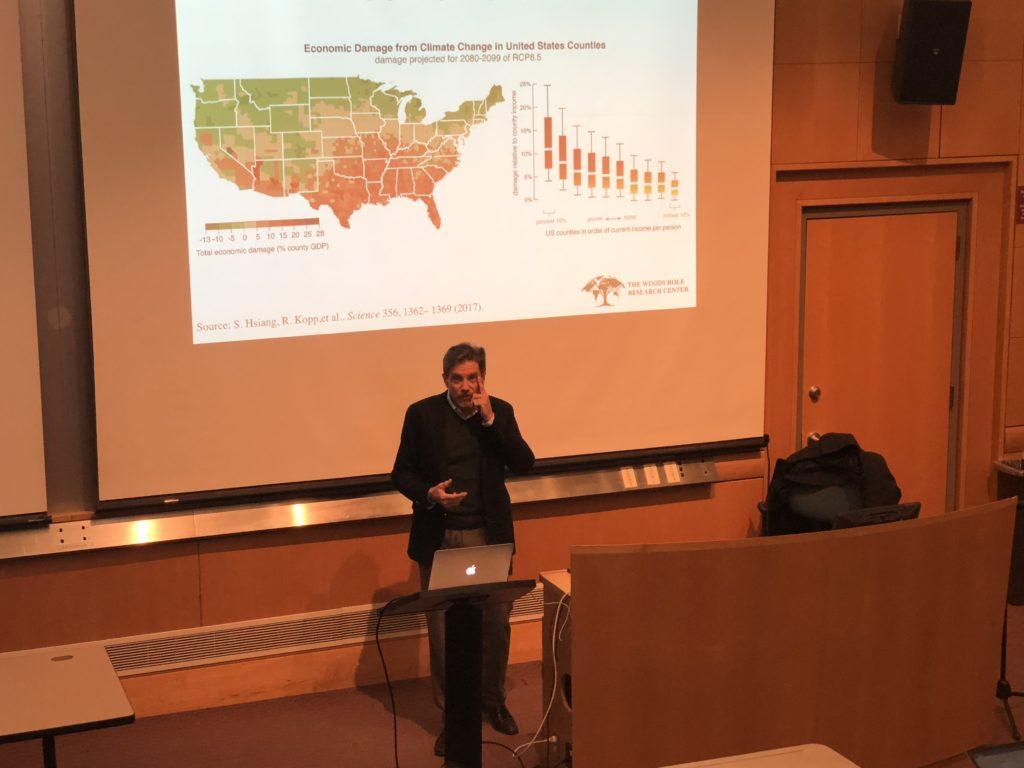

Estimates observing the six major sectors of the economy and the overall economic cost of climate change have shown that the poorest countries will likely have the greatest burden, according to Duffy.

“There are all kinds of implications here with social justice,” he said. “There are all kinds of implications here for domestic policy.”

Duffy then explained the four major tools that he perceives as the best mechanisms to limit atmospheric CO2. The first is de-carbonization of global energy, which requires a transition to wind and solar power. The second is energy efficiency, which he pointed out typically pays for itself. The next requirement involves reducing other non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions. Last but not least is CO2 removal through the restoration of natural systems that have been depleted, such as the processes of reforestation and soil restoration.

As far as public opinion on climate change is concerned, according to Duffy, polling shows that almost every state has a majority that thinks climate change exists, is caused by humans, and could be harmful to people. Yet, when asked if climate change will harm them personally, most people say no.

“Everybody thinks it’s the other guy’s problem” Duffy said. “The takeaway from all of this is that there is a lot of recognition of the existence of this problem and a lot of support for climate policy.”

Duffy pointed out an important reason for optimism: Many large businesses and corporations are beginning to grasp the impact of climate change.

“The financial community and the investment community are starting to break on climate change, and when that happens I think that’s really going to have a big influence,” he said.

Duffy explained one of the main difficulties in the fight to minimize dire effects is the human tendency to struggle with imagining a fundamentally different future. He told a story about watching a film about the 2008 financial crisis. He was fascinated to see that highly intelligent experts in finance could not believe that the housing market was going to explode, even though they could see all of the evidence.

“We cannot imagine a fundamentally different future, or a future that is fundamentally different from the past because we simply haven’t experienced it,” Duffy said.

Featured Image by Abby Hunt / Heights Editor