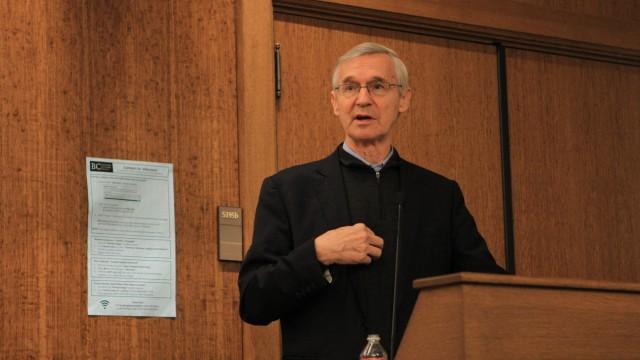

The lecture hall Stokes 195S was standing-room only on Tuesday night as Rev. Pierre de Charentenay, S.J., offered his analysis of this past weekend’s terrorist attacks in Paris and the state of security in Europe—emphasizing the importance of deep thought and emotional self-examination in the wake of violent events. De Charentenay, the Gasson chair in residence in the political science department for the 2015-16 academic year, spoke as part of “Paris: After the Attacks,” a lecture hosted by the Jesuit Institute.

“This is an opportunity for us to reflect on the Paris attacks,” De Charentenay said. “We practice days of emotion and days of prayer because these are ways to prevent events like this from happening again.”

Rev. James Keenan, S.J., director of the Jesuit Institute, praised De Charentenay’s work during his tenure as the Gasson chair. The Gasson chair is Boston College’s oldest endowed professorship, an appointment the University created over 40 years ago and one that has a history for recruiting renowned Jesuit faculty.

De Charentenay completed his doctorate in political science in Paris before serving as editor of Etudes, a Jesuit review of contemporary culture, from 2004 to 2012.

On the evening of Friday, Nov. 13, a group of eight assailants committed a series of coordinated attacks throughout the city of Paris. There were three suicide bombings outside of the French national soccer team,’s stadium the Stade de France, in addition to mass shootings and a bombing outside of a cafe. The deadliest attack came at Le Bataclan concert hall, where gunmen took concert attendees hostage, conducted a shooting spree, and later detonated explosives. The death toll for the attack has risen to 129, with 99 in critical condition and 352 injured, according to The New York Times. Just hours after the attacks ended, ISIS claimed responsibility for the carnage.

“Paris has been at the top of the terrorist attack list of ISIS—France has actively attacked Syria, and is one of the only countries currently attacking the spread of ISIS in Northern Africa,” De Charentenay said. “However, this type of attack is new in Europe. The coordination of several groups of people shows a high level of planning and use of several methods of covert communication.”

The recent attack stands in stark contrast to the Charlie Hebdo shootings that occurred in Paris in January. The shooters targeted specific individuals, while the targets in the recent attack were random.

“The public reaction to Charlie Hebdo was two to three days after the shooting, and when people reacted, the focus was on freedom of speech,” De Charentenay said. “This time was different. This time, the streets were empty the next day—a sense of longing, of fear, and of uncertainty of the future was present in Paris.”

Many ISIS affiliated groups have been thwarted in various areas of the Middle East. While they have been stopped elsewhere, however, ISIS is quickly turning to an international style of destruction, similar to the approach of Al Qaeda.

“This marks a change in force of ISIS—mass terrorism,” De Charentenay said. “We should expect in the future similar styles of attack, with fighters targeting anonymous, ‘soft targets.’”

De Charentenay took care to define how people should interpret the ISIS conflict, denouncing rush judgment of Islam.

“This is not a war with Muslims—all Muslims in Europe have denounced this attack,” De Charentenay said.

He also clarified that this is not a clash of civilizations, nor is it a war.

“War is a conflict between two identified and visible enemies,” de Charentenay said. There is a definitive start and stop to the conflict. With terrorism, the enemy is invisible: it can strike anyone, anywhere, anytime.”

He offered words of hope and encouragement to those in fear, as well as support for those seeking refuge from violence in the Middle East, particularly within the Syrian refugee crisis—a crisis that represents, De Charentenay said, a failure of the international political community for years.

“It would be too easy to call security on the refugees—they are paying for a war they never wanted—a war the international community continues to struggle to solve,” De Charentenay said.

As to how nations can continue to fight terrorism, De Charentenay believes that individuals can prevent others from being recruited into dangerous ideology.

“Terrorism is created by people, not government,” De Charentenay said. “These people are freely entering—we need to stop people from entering that deadly circle.”

Featured Image courtesy of NBC News