Entering the workforce is a scary and daunting prospect for many undergraduate students. The days of 50-minute classes and free afternoons are a far cry from the dreaded 9-5 workdays awaiting most professionals.

But what if your new job offered Fridays off without a reduction in pay? Could you keep up your exercise schedule? Redecorate your new apartment? Plan a fun weekend getaway? The possibilities would be endless.

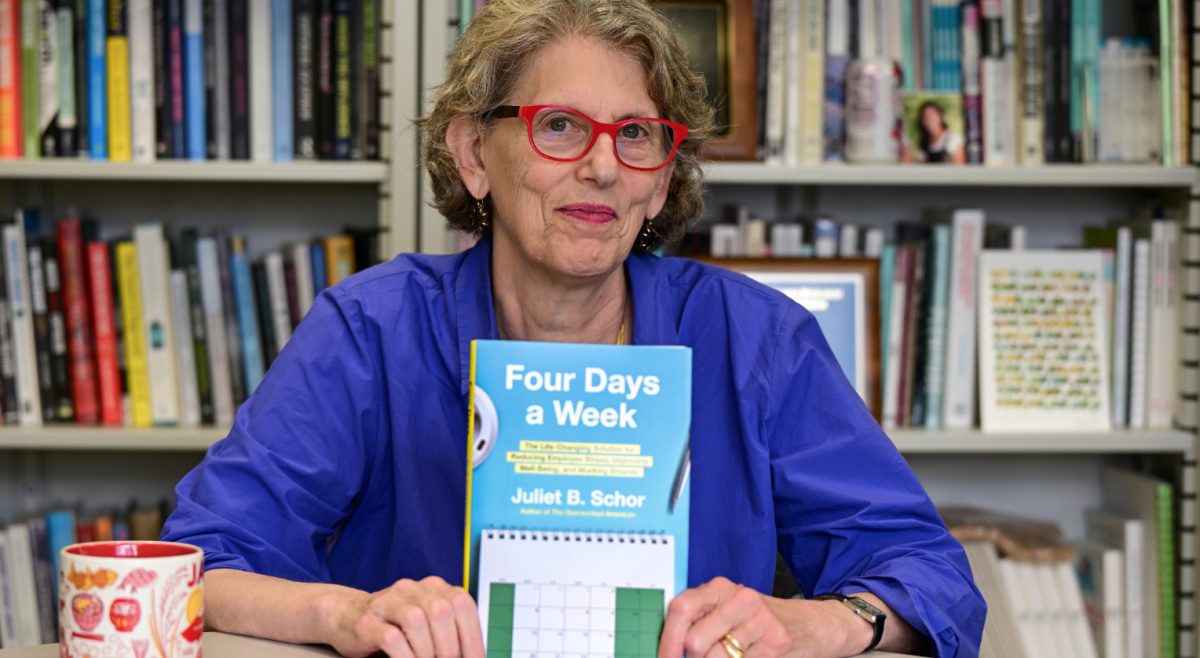

It may seem idealistic, but for Boston College sociology professor Juliet Schor, this idea is hardly far-fetched. In fact, it just might be the future of the working world.

“We need a three-day weekend, particularly for a society as rich as ours,” Schor said. “I think we’re moving in that direction.”

She came to this conclusion back in 1992 when she published her book The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. The book was groundbreaking for the time, exposing the fact that Americans are working more and more every year.

At the time, Schor was an economics professor at Harvard. She didn’t think of herself as a sociologist until an audience member at one of her talks posed an interesting question.

“‘How do you get out of the cycle of work and spend?’” she recalls the audience member asking.

Schor couldn’t think of an answer. Dissatisfied, she began to explore the world of consumption and spending. From there, she started to wonder what would happen if companies reduced their working hours without reducing pay.

Unfortunately, many companies were resistant to the idea, making it difficult to study real-world applications.

Yet, everything changed when the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020. Schor began receiving frequent requests to give talks in Europe about switching to a shorter workweek.

“People were interested in that topic, and partly for reasons having to do with climate and carbon emissions,” Schor said.

After one of her talks, Schor was approached about doing a research trial in Ireland. She jumped at the opportunity and began collaborating with an NGO called 4 Day Week Global, analyzing the data coming in via surveys while the organization handled the trial’s logistics.

The initial trial began in February 2022, and additional rounds began every two months.

These trials spanned industries and countries, taking place everywhere from South Africa to Germany, Brazil, and England.

According to Schor, the results came together in a massive data set, with more than 12,000 employees’ survey results across over 400 companies.

“Fantastic results—I mean, huge well-being improvements for the workers.” Schor said. “Companies were also very positive.”

Surveys collected employees’ responses on 20 metrics related to well-being, according to Schor. Questions asked employees about stress, exercise, sleep, work–family balance, life satisfaction, burnout, time satisfaction, and more.

The data made clear that employees had a lot to gain from some extra time.

“The bigger the reduction of working hours, the bigger the well-being gain for four different well being [dimensions]—burnout, physical/mental health and job satisfaction,” Schor said.

A two-day weekend simply does not provide enough time, according to Schor. Especially as the male breadwinner model has fallen out of practice, many homes have been left without someone to take care of chores, errands, and other jobs around the house.

Employees are also asked about other dimensions outside of well-being. In five waves of surveys, they are questioned about the “ideal worker norm.” This term describes employees’ expectations surrounding work ethic, hours worked, holding a second job, and other factors.

Additionally, employees are given a time diary to track how they spend their time during the work week.

The four-day week comes with a massive overhaul of the workday’s structure called work reorganization. This overhaul takes place over a two-month period, during which companies receive training, mentoring, and webinars on how to be successful and reduce wasted time.

“How can you reduce interruptions?” Schor said many companies are asked. “How can you make your process more efficient? What are the things you’re doing that are not really adding too much value to your company, and that you could scale back on or stop so that people can get all their work done in four days?”

This restructuring process has allowed companies to flourish under the four-day workweek.

The story of these trials can be found in Schor’s latest book published this past June titled Four Days a Week: The Life Changing Solution for Reducing Employee Stress, Improving Well-Being, and Working Smarter.

One success story Schor highlighted is Liz Powers, co-founder and CEO of ArtLifting, a startup that helps artists with disabilities sell their work.

Powers had always been curious about the idea of the four-day week.

“How can you work smarter, not harder?” Powers said. “A clear way of doing that is being well-rested.”

After reading an article in 2019 about the four-day workweek, she was sold.

“To have better work-life balance—what a no-brainer,” Powers said.

In 2019, she started testing out the four-day workweek in what she called the “stair-step test.” Her company gradually increased the number of months a year that it would operate on the shortened schedule.

When Powers watched a popular TED Talk Schor gave on the four-day workweek, she immediately reached out to share her company’s experience.

ArtLifting’s process for shortening the workweek involved implementing agendas for meetings, designated “focus time” from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.—during which employees didn’t schedule recurring internal meetings—and utilizing a project management software called Asana.

The rise of problem-solving and creativity in her employees was tangible.

“When we had this extra rest time with the three day weekend, we’d be unconsciously solving problems during the weekend,” Powers said. “It made it so when you got back into the office on Monday morning, like this thing that felt unsolvable at the end of the last week, like, ‘Oh, I can bang this out in 15 minutes now.’”

Powers can’t imagine switching back to a five-day workweek.

“It feels nearly impossible to be creative if you feel like you don’t have space for your brain to think,” Powers said.

Now, Powers said that not only are her employees able to be creative, but are also better able to take care of themselves.

“We’ve seen in anonymous surveys that they’re able to go to doctors appointments on Fridays,” Powers said. “People really appreciate having extra time for personal and professional development or visiting family members who are sick.”

This flexibility plays a big role in helping attract and retain quality employees, Powers said

Schor has seen these positive outcomes replicated across her trials.

“It’s a very valuable policy for attracting and retaining work employees because people tend not to quit at four-day week companies,” Schor said. “They love being at a four-day company.”

Wen Fan, Schor’s co-lead on the project and an associate professor of sociology at BC, described the four-day workweek as a “win-win-on-win.”

“It benefits employees because we just had a Nature Human Behaviour paper that demonstrated the well-being benefits of participating in four-day workweeks, and it’s also benefitting companies in terms of reducing turnover rates and maintaining and sometimes even improving their revenues,” Fan said. And it also benefits our society.”

The societal benefit has come in two parts: gender equality and environmental impact.

“We have seen some evidence that it helps with gender equality, that many men, for example, can begin to pitch in with housework and so on if they have more time at home,” Fan said. “It also could benefit the environment in general.”

The environmental impact, though, is not quite as significant as Schor had originally anticipated, partly because many people were already working from home.

Over time, with the expansion of the four-day workweek, Schor believes there could be a tangible impact on carbon emissions.

For Schor, much remains to be explored about the four-day workweek. Her drive to keep researching the topic inspired Guolin Gu, a PhD student in the sociology department, while working alongside Schor on the project.

“She has a lot of drive to understand more about the issue and to study it from all possible angles,” Gu said.

The trials often come with many challenges, according to Fan.

“It’s not like you are doing an experiment in a lab,” Fan said. “We are talking about actual humans. They are doing things that we might not want.”

Still, Schor was never deterred, Gu said.

“I think it takes a lot of fortitude and belief in what you’re doing, in the topic being a worthwhile one to study, and to find all different possible ways that exist to study it,” Gu said.

Schor’s deep dive into her research is something Gu says is not unique to the four-day week project. In fact, it extends into her work at BC.

“She’s good at choosing novel topics and to study novel social phenomena, new things that emerge,” Gu said. “And to be always on the frontier of what is possible for change.”

But what has stood out to Gu above all is how much Schor cares for her students and their research.

“Her mentorship for her students is something that I’m learning from,” Gu said. “It’s something that I want to be if I ever become a professor.”

Schor’s excitement for her own research, however, may be unreplicable, according to Gu.

“I don’t think I’ll be as passionate about my research as she is about hers, but it’s something I am aspiring for,” Gu said.

Schor’s enthusiasm hasn’t faded, and she has big plans for the future of a shorter workweek.

“I think about a 10-year evolutionary movement,” Schor said. “I think maybe near the end of that period, we might get some legislation about it.”

The result would be drastic improvements across many different sectors of human life, according to Schor.

“You’ll see it in health, you’ll see it in family, the health of families and communities,” Schor said. “People’s quality of life will go up a lot. I think people will be happier. I mean that’s what we’re seeing in our studies. People are just a lot happier.”

There are always more questions to ask as new data continues to surface, Fan said.

“As more data comes in, we can begin to think about other questions—the connection between AI and work time reduction, things like that,” Fan said.

Fan doesn’t see their work finishing anytime soon.

“It’s hard to predict when it’s going to end,” Fan said. “So maybe never, because it’s going to be a long-term social movement. It’s a great privilege to be part of the change.”

For Schor, the four-day workweek simply makes sense.

“Two days is not enough,” Schor said. “People just need a third day.”