It’s hard to imagine George Marshall, former secretary of state and secretary of defense in the ’40s and ’50s, taking a selfie, David Brooks said. We are sitting in the backseat of a car, being driven down Commonwealth Ave. from Coolidge Corner back to campus, and talking about the necessity of social media. It is raining outside the window, and the late-summer humidity permeates the interior of the car. He is wearing a purple tie and a dark suit, too hot for the weather outside.

Brooks, who is more soft-spoken than his gregarious columns in the New York Times on love and politics make him seem, does not have a high opinion of social media. He goes on to decry his friends and colleagues who use Facebook to blatantly promote themselves.

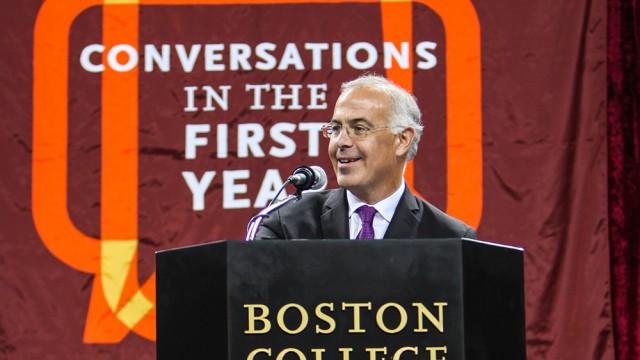

“The people I read about would not have liked that,” Brooks said in reference to the people he wrote about in his most recent book, The Road to Character. A committee headed by Elizabeth Bracher, the associate director of First Year Experience, selected the book to be the required reading for the class of 2019. On Thursday, Brooks, a professor at Yale University as well as a regular New York Times columnist and, spoke at the First Year Academic Convocation.

I had had an hour-long meeting scheduled with Brooks, but due to a miscommunication, the meeting was trimmed to a 20-minute car ride between his hotel and Boston College.

Brooks’ homebase is in Bethesda, Md., where he lives in the same neighborhood as my family, though I did not know that until our meeting. I knew he lived around D.C., but when I found out that his house is close to my elementary school, I gasped with excitement. If they hadn’t gone to private school, his children would have been classmates with my brothers and me.

In Bethesda, only 40 percent of people identify as religious, but 10 percent of those people are Jewish. At BC, 70 percent of students identify as Catholic, and 2 percent as Jewish. Coming from Yale, he expected that BC students would have slightly more religious literacy than the average university student, but that students everywhere face similar kinds of resume pressures. I point out the oddity, for me, of coming to BC from Bethesda, where religion has never been a focal point.

“The religious orientation gives the school a little more moral content than your average resume factor and that’s a good thing,” he said, a bit later in the conversation. “The challenge is tying what you learn on Sunday into the other six days of the week.”

Brooks’ writing skews conservative, which is unusual coming from Bethesda, home of liberal pundits E.J. Dionne and Thomas Friedman. (Disclosure: Dionne’s middle child and I were in the same grade in high school, and worked together on the school’s newspaper.) Brooks and Dionne share a program on NPR, and are close.

“It’s funny, I know the liberal ones more,” Brooks said. “They’re always pairing us … We get together. Often we’ll get invited to see the president together, eight of us or so. I think it helps because you see a sensible person on the other side, it helps to have daily contact with people who disagree with you.”

“It helps to have daily contact with people who disagree with you.” -David Brooks, New York Times columnist

Brooks could seem like an unusual choice for a speaker at a Jesuit institution, because he’s Jewish and, though conservative, fairly middle-of-the-road.

But, the values espoused in his book line up pretty closely with the Jesuit ideal of finding your authentic self, so he isn’t really a surprising choice.

Two years into the four-year process of writing The Road To Character, he hit upon Joseph Soloveitchik’s writings about Adam I and Adam II, the two images of Adam in the Book of Genesis. Adam I is ambitious, whereas Adam II is humble. Brooks uses these two sides of man to talk about resume and eulogy virtues, and the importance striking a balance between career success and moral success.

“The resume virtues are the skills you bring to the marketplace,” Brooks wrote in a column in the New York Times this spring. “The eulogy virtues are the ones that are talked about at your funeral—whether you were kind, brave, honest, or faithful. Were you capable of deep love?’”

As he has grown older, Brooks thinks more about his inner life. This is not unusual for someone of his age, he said, and for someone who has gained career success but still does not feel fulfilled. He hadn’t thought about his book over the summer months—instead, he was caught up in going to the beach and having fun, he said.

On the plane here from Russia, he skimmed through it again. Hopefully, he said, since hitting upon the distinction between resume and eulogy virtues, he has become more aware and better at relationships.

The Road To Character is a hefty book, with stories of several influential, moral figures, from Dorothy Day to George Marshall. At times, it can feel a bit preachy—all of the people highlighted in the book are living their lives so effectively with personal moral codes that can seem unattainable.

Sitting in the back seat of the car, it occurred to me that this man, who reminds me of my father and all of my friends’ fathers back in Bethesda, could not possibly have all the answers the book seems to contain.

And Brooks acknowledged this in the introduction to the book, when he he said that he is not sure if he himself could follow the road to character, but that he wants to know what it looks like.

“I thought, gee, I’m not really living as well as I should be,’” he said about re-reading his book. “This book is better than I’m actually living. And so I was like, ‘I gotta get back on the program.’ I certainly felt inadequate … life is still hard.”

Brooks teaches at Yale because when he writes columns, he knows it goes out to a lot of people, but he can’t actually see them. When he teaches, he likes being able to see the same students 14 weeks in a row. At Yale, he holds his office hours in a bar, so students can come and chat with him. The last time Brooks spoke at BC was in 2010, when he spoke in a talk sponsored by the Winston Center for Business & Ethics.

He wanted to come back to speak again at BC because he was honored by the thought of students having access to his book, he said. His book tours tend to be filled with 70-year-olds who have already lived their life, but coming to BC lent him the opportunity to influence 19-year-olds.

“At the top tier schools, people come in very similar,” he said. “They leave very different.”

Featured Image by Drew Hoo / Heights Editor