Over a decade after the 2008 recession, law schools across the country—including Boston College Law School—are still grappling with the fallout of a shrinking labor market and decreased enrollment, trends that have only recently—and barely—reversed themselves.

Beginning in 2012, law schools around the country saw their enrollment numbers drop dramatically. Data from the American Bar Association (ABA) showed that basic law degree—a Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree—enrollment peaked in the 2010-11 academic year at just over 147,000 students. That same year, there were a record-high 52,000 first-year law students.

Both figures consistently decreased over the next several years, falling to a record-low 110,176 J.D. students enrolled for the 2017-18 academic year—one year after first-year enrollment finally improved.

This year, things finally looked up for law schools. National J.D. enrollment increased for the first time since 2010-11, reaching 111,561, while first year-enrollment rose again. In an article published earlier this year, the Boston Herald interviewed several law professors and law deans, many of whom suggested that the Trump administration may have inspired college students to pursue law.

BC Law Dean Vincent Rougeau agreed that the “Trump bump” theory could have merit.

“There’s definitely a lot of interest amongst incoming students around public policy, making a difference, and understanding how the law impacts our democracy,” Rougeau said. “I think that what the President and this administration and this whole political era have done is awaken a lot of people to some basic civics lessons about how the government operates, how the legislature operates, and what the consequences of certain political activities are.”

But while the current political environment may been drawing more attention to the field, law schools have a long way to go to reverse the overall negative trends in interest.

“There was a big drop off in interest in law school after the recession in 2008,” Rougeau said. “That was an economic reaction because people used to see law as a good way for someone with a strong liberal arts undergraduate background to enter a professional field that had good prospects professionally and economically.”

Following the recession, prospective law students changed course to more promising fields, especially the finance industry and Silicon Valley.

He also explained that law school across the country purposely limited enrollment in the years after the crash—leading to the downward trends identified in the Herald report.

While national trends in first-year enrollment have turned around, BC is yet to catch up. First-year enrollment fell nine percent from last year.

“We made the decision that we should decrease the size of our classes to account for the fact that the job market has contracted,” Rougeau said. “There were a lot of recent law graduates in that [post-recession] era looking for work, and it was taking them a lot longer to find it or they weren’t finding the same quality of work.

“Meanwhile, law schools were realizing, ‘we can’t keep graduating large classes of lawyers or large classes of graduates when the employment prospects have declined.’”

That decision compounded the natural aversion undergraduates had to law school at the time, leading to simultaneous lower application and enrolment numbers. Despite a decade of economic growth and the aid of a new generation of law students, Rougeau said that interest in law school is unlikely to fully recover to pre-2008 levels.

One factor is that the number of jobs has not yet bounced back to pre-2008 levels. The market for lawyers is less crowded than in the years following the recession, but mostly as a result of lower law school enrollment, not new employment opportunities.

“There’s a better balance between supply and demand,” Rougeau said. “Demand hasn’t soared. It’s up, but it hasn’t soared. Now that there are fewer actual graduates looking for work, it’s a lot easier for those graduates to find work because demands has improved enough to absorb them.”

In the event of a future major recession, Rougeau sees the new generation of law students as a major asset. In his eyes, their interest in public service has inoculated them against chasing more profitable career paths—a mindset that pushed many away as the job market contracted.

“I’m not counting on law school enrollments to return to their pre-2008 levels, because I think that was the end of a different time for lawyers,” Rougeau said. “You can’t go to law school because you think that right after you graduate, you’re going to get a $180,000 job at a big law firm on Wall Street or downtown Boston.

“If you’re entering the legal profession these days, that’s because you really see the public side and the ways it really is essential to the way our democracy works.”

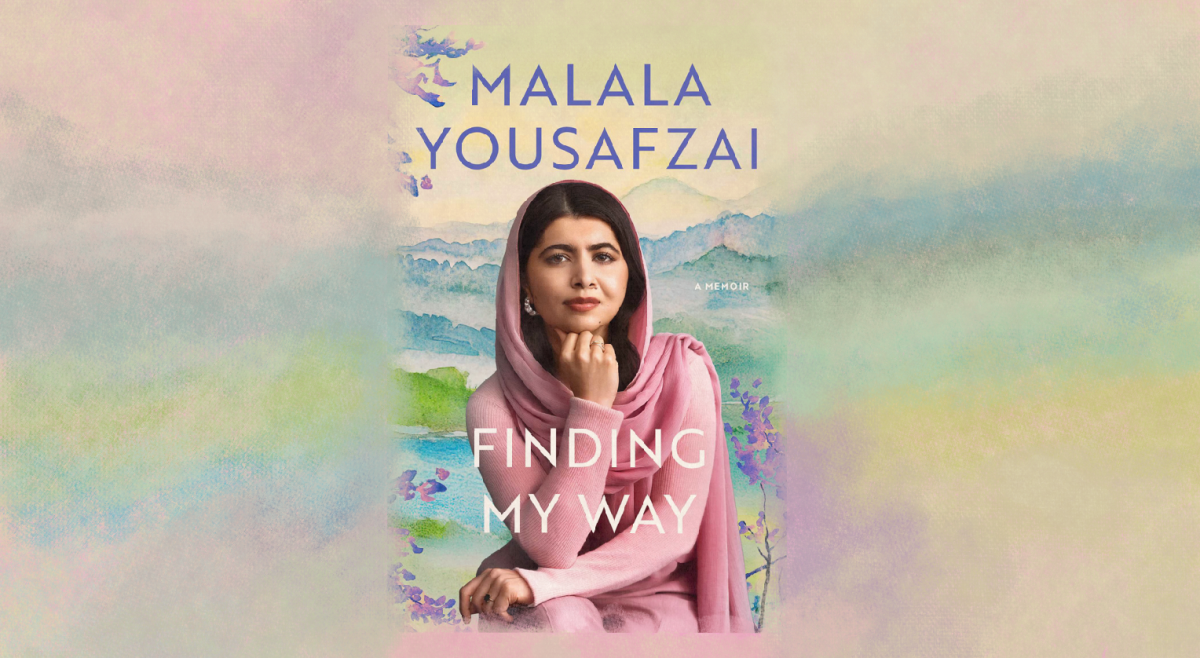

Featured Image by Jonathan Ye / Heights Editor