“I woke up to Sofia screaming her head off,” said Caroline Shannon, Megale’s direct roommate and MCAS ’24. “I thought it was like a terrible, terrible nightmare.”

Hearing the commotion, one of Megale’s suitemates burst through the door and identified a flying creature—a bat.

Megale, MCAS ’24, said she and her roommates left their suite on Feb. 10 and waited in the hallway as Shannon got their RA, who then made calls to the Boston College Police Department (BCPD) and BC’s Facilities Management. Around 20 minutes later, Megale said facilities arrived and captured the bat.

“The guy was holding the bat in a towel, and you could see its fangs and everything,” said Avery Boniface, one of the suitemates and MCAS ’24.

The roommates told facilities the bat should be tested for rabies, since Shannon was asleep in the room with the creature and it touched Megale repeatedly, Shannon said.

“I made it clear to them … that I was touched by it, and that it’s not safe to let it go because we would just have to get rabies shots then,” Megale said.

A Walsh RA said facilities agreed to place the bat in a bucket and later bring it to BCPD after the Walsh 8 residents and their parents—who the students were speaking with on the phone during the incident—expressed concern about getting the bat tested for rabies.

“Their parents wanted to make sure that their kids were safe, and they really thought that getting it checked [for rabies] was the best thing to do,” she said. “The girls were very adamant about getting the bat tested, and I don’t know what ended up happening, but I really hope they were able to.”

The following morning, Shannon said she went to BCPD’s office in Maloney Hall but was told it had no record of what happened and to call facilities. According to Shannon, facilities told her to call back later. Megale said another roommate called facilities later that day, which said it had released the bat.

“We were … a little bit shocked they did that because we had been so adamant the night before that [they] could not let it go,” Megale said.

Jack Dunn, associate vice president for University communications, said that the students informed facilities they had not been bitten by the bat.

“They were offered support from their RA and told to contact University Health Services, which instructed the students the following morning to get tested for rabies,” he said in an email.

According to Philip Landrigan, director of BC’s global public health program, if a bat is found in a room, you must presume it is infected with rabies.

“Especially if it’s a situation where people are asleep, or semi-asleep, you have to presume that they have had contact with a bat and perhaps even a bite,” Landrigan said.

Facilities’ decision to release the bat aligned with its standard wildlife protocol—though BC is now changing this policy, according to Dunn.

“Admittedly, Facilities has not had a lot of experience in dealing with bats inside of the residence hall rooms,” he said. “Moving forward, Facilities will make it their policy to contact Animal Services in Boston or Newton should a similar incident occur in the future.”

Facilities did not respond to a request for comment.

Landrigan said that standard protocol for a potential rabies contact is to capture the bat and notify public health authorities.

“It’s standard protocol with a potential rabies contact to capture the bat and get it into the hands of public health authorities,” he said. “It doesn’t always happen for practical reasons, but that’s the ideal protocol.”

Any contact with a bat has to be taken seriously, as even the most minute scratch from a bat can potentially transmit rabies, Landrigan said.

“This is a very serious situation,” Landrigan said. “You have to presume in this circumstance that both of these students had contact with the bat, and if they have not immediately started … postexposure prophylaxis [treatment], they must begin it ASAP—this is a real medical emergency.”

Shannon and Megale are now receiving rabies vaccines at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center for their potential exposure.

According to the CDC, the treatment for potential rabies exposure—or postexposure prophylaxis—includes a dose of human rabies globulin and rabies vaccine given on the day of exposure, and then additional vaccine doses on day three, seven, and 14.

Shannon and Megale will make five trips to the emergency room to receive their shots, which will be fully covered by insurance for Megale, but cost Shannon around $1,250 in copays.

Mark Pearlmutter, the chairman of emergency medicine at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, said they will almost always treat someone for rabies if they woke up with a bat in their room—as Megale and Shannon did—regardless of whether there is a bite or scratch mark.

“We generally will treat someone who comes in who says they woke up with a bat in their bedroom,” Pearlmutter said. “And the proper way to handle this is to bring in a public health officer, an animal officer, that can actually find the bat, trap the bat, and then check it for rabies.”

Ann Scales, the director of media relations for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, said in an email that if a person had contact with a bat in which a scratch or bite could not be ruled out, it is the state’s public health recommendation that the bat be sent to the state public health lab to be tested for rabies.

Pearlmutter said though it is very rare, there have been a few instances in the country where transmission of rabies occurred after someone woke up with a bat in their room and saw no visible abrasion.

“They did not have any signs of being bit or scratched—and that’s not infrequent, by the way—and there were one or two cases where folks did get rabies,” he said. “So that shifted a lot of the treatment recommendations to lower the threshold in those instances and actually administer the immunoglobulin for rabies as well as the vaccine for rabies.”

Shannon said it felt irresponsible for facilities to release the bat because it compromised her and Megale’s safety.

“Now Sofia and I have to deal with this,” Shannon said. “We’re right at risk for a fatal disease, and we’ve just spent all this money to go through this, get nine shots, so that we don’t have rabies.”

Rabies is almost always fatal if left untreated, according to Pearlmutter.

“If you actually do get infected, the mortality rate is extremely high,” he said. “And once it’s taken its course, meaning once it’s actually entered into your body, while there is some supportive treatment, it’s a very lethal disease process.”

Shannon said she wishes facilities or BCPD would have told her to call a regular exterminator if they were not going to keep the bat for testing.

“We are told that when we have an animal or something in the dorm, we’re supposed to call maintenance and BCPD, and I think … if they’re unable to handle keeping a bat overnight so we can get [it] tested for rabies, which is the number one thing that you’re supposed to do [in this situation] … they shouldn’t be doing that job,” Shannon said.

BCPD did not respond to a request for comment.

According to Landrigan, the students would need to get treated regardless of whether the bat had rabies.

“They still would have had to have been treated because it takes a few days to examine the bat and you don’t dare to wait a few days before you initiate treatment, so it would not have changed the treatment that the girls received,” he said.

Megale wishes she was given clear and explicit answers during the situation.

“A bat landed on me multiple times and there should be someone … making me feel reassured and not in danger,” she said. “And I feel like there’s just a lack of that.”

The Office of Residential Life did not respond to a request for comment.

Erin Shannon and Eliza Hernandez contributed to reporting.

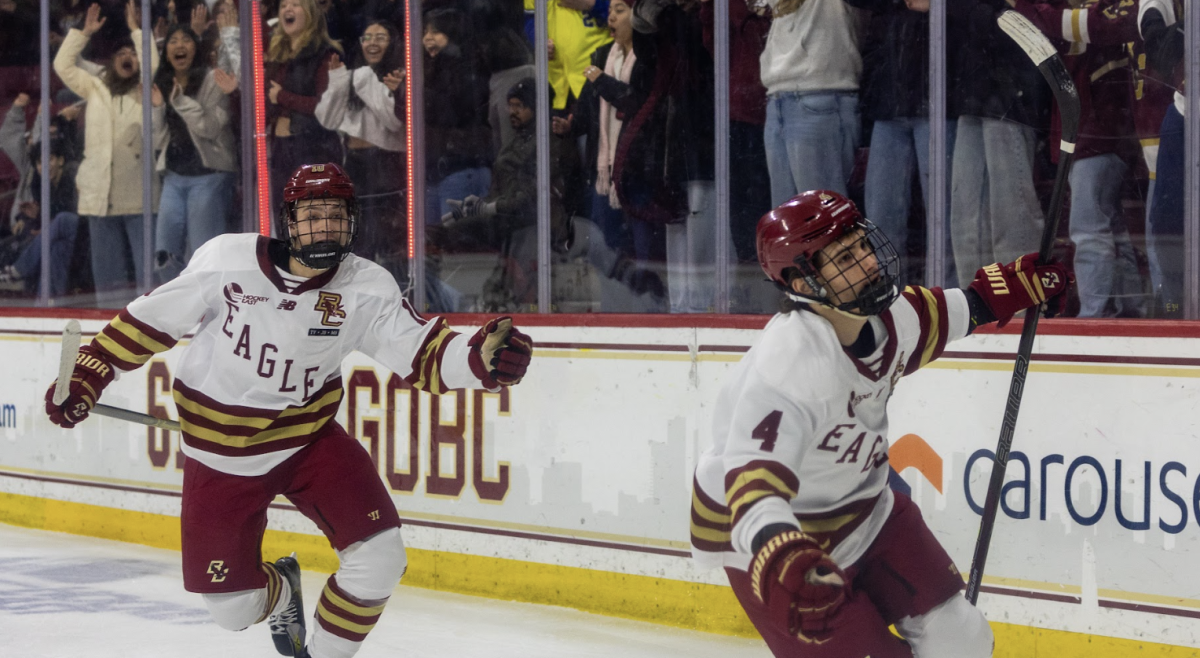

Featured Image by Steve Mooney / Heights Editor