Danya Abrams was a projected first-round pick in the 1996 NBA Draft following his junior season at Boston College. With that in mind, many players would have ended their college careers early and declared for the draft.

But there were things keeping Abrams at BC—more for him to do, both on and off the court.

“I had promised my family I would get my degree,” Abrams said.

Not to mention the fact that he loved BC.

“He just didn’t want to leave,” Tom Devitt, a graduate assistant at BC during Abrams’ career, said. “He loved Boston College, and he loved being a college kid. He loved being a BC Eagle.”

Abrams ended his BC career as one of only two players in the program’s history with 2,000 career points and 1,000 career rebounds but ultimately didn’t end up in the NBA.

He ended up traveling the world for free, though.

Then he launched his own company and co-started another.

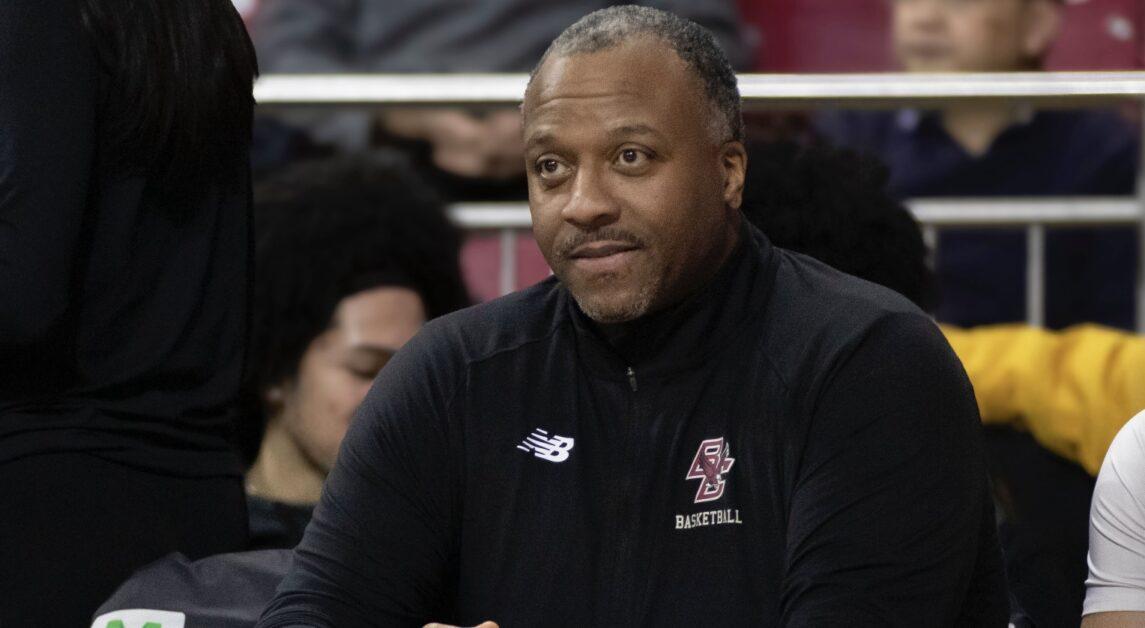

And now, Abrams is back where it all started: on the court with BC men’s basketball.

“For it to come full circle, for me to come back and to be a coach at my alma mater,” Abrams said. “It’s a dream come true.”

It’s not every day that college basketball coaches stand on the sidelines of a high school football game in hopes of converting a football player to a basketball commit.

But there BC men’s basketball coaches Jim O’Brien, Paul Biancardi, Dave Spiller, and Rick Boyages were, standing on the sidelines to watch Abrams play football.

“They were the only basketball coaches to come to my football games to recruit me, and that’s how they won me over,” Abrams said. “There’s, you know, all these DI football programs, and you see on the side these basketball coaches … I was like, ‘Yeah, they’re committed.’”

BC beat out John Calipari at UMass Amherst to secure Abrams’ commitment in the fall of 1993. The choice wasn’t entirely about basketball, though.

“I am not minimizing UMass, but I valued education and I had a lot of people that I knew that went here, and older people that went here, and they were successful in life,” Abrams said.

Abrams made the move from New York to Boston, where he’s been ever since. Initially, he thought he would go back to New York one day. But after meeting his wife at BC, that plan changed.

“She had other plans, so I lost that fight,” Abrams said with a chuckle. “It’s not a bad one to lose.”

Before Boston became home, Abrams grew up in New York City, playing basketball for fun at the YMCA and in community centers. He says he loved his childhood and that it made him into the person and player he eventually became.

It also influenced a lot of the decisions he made.

“We lived in the housing projects, so for me it was normal,” Abrams said. “You know, you don’t know what’s normal as a kid. But once I went to preparatory school, and I saw how a lot of people were living, it made me want to do more and be better, get a great education, and build the life that I have now.”

When Abrams realized he could use basketball as a means to an end, he began to take it more seriously. Even so, he wasn’t attending five-star basketball camps during the summers or playing in front of many recruiters.

“The reason why, I guess, I went underrated, was because during the summer, I always went to football camps and just stayed home,” Abrams said. “So when I was invited to five-star back then, and all these other national camps, I didn’t go because I was doing football and having fun with it.”

When reflecting on his basketball career, Abrams immediately acknowledged the help he got along the way, especially in his young years.

“Both my uncles were very instrumental in the basketball field for me,” Abrams said. “I lost my father at an early age, so my mother’s brothers basically raised me and helped me out.”

Abrams’ mother’s brother, his “Uncle Rodney,” played basketball at UNC Charlotte. As Abrams grew into his basketball career, Abrams says it was his uncle who pushed him to achieve greatness.

“He’s the one that inspired me to say that I could do it,” Abrams said. “If he could do it, I could do it.”

That guidance paid off. Abrams went on to become a BC legend.

Madison Square Garden is hardly the place you want to lose as a basketball player. Especially not in a blowout. Especially in the Big East Tournament.

During Abrams’ freshman season at BC, that’s exactly what happened in the Eagles’ first postseason game of the 1993–94 season, as the No. 3-seed Eagles were blown out by 23 points by No. 6-seed Georgetown.

A week later, the Eagles were set to face No. 8 Washington State in the first round of the NCAA Tournament. Coming off consecutive double-digit losses, their chances at a deep run didn’t look too good.

But miracles do happen. That season, the Eagles pulled off what went down as the most incredible run in program history.

They started with a three-point win over Washington State in the opening round of the NCAA Tournament. Waiting next for BC was first-ranked North Carolina, arguably the best team in the nation.

“The year before, I was sitting home in my living room watching North Carolina win the national championship, you know, not ever thinking that we’d get to play against them,” Abrams said.

Somehow, the Eagles found a way to knock off UNC—home to big names such as Jerry Stackhouse, Rasheed Wallace, and Eric Montross at the time—and BC fans watched in delirium as their team defeated the defending champs and advanced to the Sweet Sixteen.

The Eagles were eventually bounced from the tournament by No. 14 Florida in the Elite Eight. Regardless, their deep playoff run proved just how far a smallish Catholic school in Chestnut Hill could go.

That year, Abrams joined a BC starting lineup composed of Bill Curley, Howard Eisley, Malcolm Huckaby, and Gerrod Abram—all seniors. But that age gap didn’t matter.

“He fit in on day one,” Abrams’ BC teammate Marc Molinsky said. “That is very unusual for a freshman to do in any program, much less a Big East program, and a program that … had a solid team in place already.”

Abrams averaged 10 points and seven rebounds in his freshman year. He scored 14 points in the Eagles’ second-round win over UNC.

“[The Tar Heels] were stacked with All-Americans,” Abrams said. “For us to play against them and beat them, and then get to the Elite Eight—I thought every year was going to be like that.”

Every year did not go like that, though.

“The four seniors graduated,” Abrams said. “And our sophomore year, we got our butts kicked.”

BC went 9–19 Abrams’ sophomore year and missed the NCAA tournament less than a year after coming within striking distance of the Final Four.

“We were two minutes away from the Final Four against Florida the year before,” Devitt said. “And then, you know, six months later, we’re trying to figure out who our starting point guard is going to be.”

Nonetheless, Abrams continued to shine.

“Those two concurrent years, he treated each scenario the same—and that’s a really, really incredible skill,” Devitt said. “He didn’t like to lose at all, but the way he responded to losses, and the way he responded to victories, he was still the same person.”

Abrams scored 68 points in a 24-hour span in the Big East Tournament, becoming the first player in tournament history to have back-to-back 30-point games.

“He went from being a second or third option to being the only option,” Devitt said. “And he did it seamlessly. He really did.”

Abrams’ sophomore year was the best year of his college career scoring-wise. He averaged 22 points per game, but individual success wasn’t enough for Abrams.

“I just didn’t like that feeling of not making the NCAA Tournament,” Abrams said. “I vowed that the next two years, we were going to be in the NCAA Tournament, if not try to win the national championship.”

Abrams said that summer was the hardest he ever worked. And after that summer, he never missed the NCAA Tournament again.

“He was still the same person who really liked laughing it up with the employees at the dining services or the folks in facilities,” Devitt said. “Whether we won 25 games or lost in a season, none of that changed him at his core, and that’s something that is really important when you’re teaching and coaching.”

It wasn’t size or an extremely complex skill set that placed Abrams in the first tier of talent in the Big East. It was his toughness.

“You can imagine the toughness that would be required for him to compete at such a disadvantage and still be the best,” Molinsky said. “You can imagine what type of character, what type of work ethic, what type of toughness would be required for him to be arguably, you know, the best, or one of the best big men in the Big East when he was possibly the shortest.”

Devitt recalled a scramble for a loose ball in a game against Syracuse. Danya jumped into the pile on the floor to grab the ball, with three orange jerseys surrounding him.

“Danya would pop up to his feet with the ball under his arm, and the other three Syracuse guys would be slowly getting up, like holding body parts in pain, you know?” Devitt said. “And that was him.”

BC didn’t come close to a national championship win during Abrams’ tenure. But the Eagles were perennial tournament contenders as Abrams helped a winning culture ripple through the program. The crowd in Conte Forum was routinely like the crowd at BC’s recent Duke game—loud and energetic—a big contrast from the crowds the current program regularly draws.

“My nickname for him is 20 and 10, because it was pretty much a guarantee that he was going to get 20 points and 10 rebounds every single night,” Molinsky said.

Abrams averaged 17 points per game over the course of his career and graduated as a three-time First-Team All-Big East player and two-time All-Big East Tournament player.

The Eagles beat Villanova in the Big East Championship at Madison Square Garden as Abrams neared the end of his career. He says that senior-year win was the pinnacle of his BC career.

But just as important for Abrams was that his time at BC culminated in something unrelated to basketball: his degree.

“You could never take away my degree that I got from BC,” Abrams said. “That set me up for life after basketball.”

After graduating from BC, Abrams had the chance to work out with the San Antonio Spurs organization. But then an offer came from a European team promising a bigger starting salary and, importantly for Abrams, lots of playing time.

“He’s just very unique, because he could have been on a number of NBA rosters,” Devitt said. “I remember him saying to me, ‘Why would I want to be 9, 10, or 11 on an NBA roster when I’m the focal point in Spain?’”

So Abrams went to Europe and ended up staying there for 12 years, playing eight years in Spain and four in Greece.

During that time, basketball was Abrams’ first priority. After all, that’s what he was getting paid to do. But while putting on big scoring performances, competing in the EuroLeague, and playing in FIBA cups, Abrams also got the chance to see the world.

“I’ve been to Moscow, Ukraine, Czech Republic, Poland, France, Greece, Germany, up and down the European sea, where I’ve been to Israel, Tel Aviv,” Abrams said. “All these places that you look at, you may not be able to get to—I get to go there for free and play a game that I love and get paid for it.”

Eventually, Abrams’ career ended and he moved back to Boston, where he lives with his wife and three children.

Just like he seamlessly fit into a lineup of seniors and helped his team to the Elite Eight as a freshman, Abrams seamlessly transitioned into the business world after retiring from professional basketball.

“Starting your own business is one of the toughest things that anyone can do in their lifetime,” Molinsky said. “Almost similar to the way he came into our team as a freshman, he made the transition to being a successful business person seamlessly, because he’s just a really smart and savvy guy.”

Abrams worked at MassMutual before deciding he was ready to branch off and start his own company. The result was Abrams Insurance and Financial Services, the first of his two companies.

“I had that entrepreneurship spirit, and I went out and started it,” Abrams said. “That was about 12 years ago, and the rest is history.”

Abrams credits his success in part to the help from people he met at BC. It was no coincidence that the job that got Abrams back on the court—this time, as a coach—came about due to another BC connection.

Devitt, the head coach at Wentworth at the time, asked Abrams to join his staff several times before Abrams agreed.

“Our guys would be mesmerized by him,” Devitt said. “He just, he could capture a room—he still can. But his overwhelming positivity for life and for basketball is something that just strikes me daily, still, about him.”

Abrams decided to give coaching a try and ended up falling in love with it. His passion for working with student-athletes doesn’t end on the court, though.

Abrams is responsible for co-starting Diverse Athlete Placement, a program that helps former athletes complete the necessary steps to get into the workforce after retiring from their sports. That includes skills like writing, dressing professionally, and crafting resumes.

“When I finished playing basketball in Europe and I came home, I just wanted to be able to help student-athletes be able to get into the workforce and understand that it’s okay to ask for help,” Abrams said.

Abrams has a diverse set of passions—he wouldn’t have started two companies if he didn’t. But right now, his focus is back where it was in the 1990s, just in a different form.

While Abrams builds his career as the director of roster management for BC men’s basketball, he’s putting the values of teamwork he learned on the court to use.

“My main function is here at BC, but those two companies are my pride and joy—I still love it,” Abrams said. “But the good thing about being a team player and understanding sports is that you have to have a team to win. And if it was just me about Abrams’ Insurance, if it was just me about Diverse Athlete Placement, it wouldn’t succeed. So I’m happy to delegate and empower other people to perform and run the company, where I can now do my love and lifelong dream job here at Boston College.”

Abrams’ return to BC comes at an interesting time. He has to adapt to the ever-changing landscape of college sports—which includes handling name, image, and likeness deals, as well as managing recruitment and player retention.

Abrams isn’t complaining, though.

“Boston College is home, and it’s the place where we all experienced arguably the best times of our lives,” Devitt said. “So why wouldn’t we want to return? Why wouldn’t we want to convey our happy times to a new group of athletes and a new group of students? It just seems so natural to want to convey the place that made us feel happy and the place that made us feel at home.”

Abrams can’t help the Eagles by scoring 2,000 points or scrambling for loose balls, but he’s found a new way to uplift the program.

“The first thing that he does—and even now at BC I see it all the time—is he puts his arm around a player, and he ultimately just gets to that player’s level and mindset, wherever that may be,” Devitt said. “He never speaks down to anybody. He’s always uplifting folks.”

Abrams has a wife and three kids now. He’s traveled the world. He’s started two companies. But his current goal for BC is the same goal he had back in 1994 when he stepped on the court to face No. 1 UNC: win.

“I plan on being here for years to come with Coach Grant and staff,” Abrams said. “Using my expertise and his expertise to build this program into a powerhouse.”