★★★☆☆

Luca Guadagnino’s newest film, After the Hunt, presents an intriguing and potentially controversial departure from his typical style.

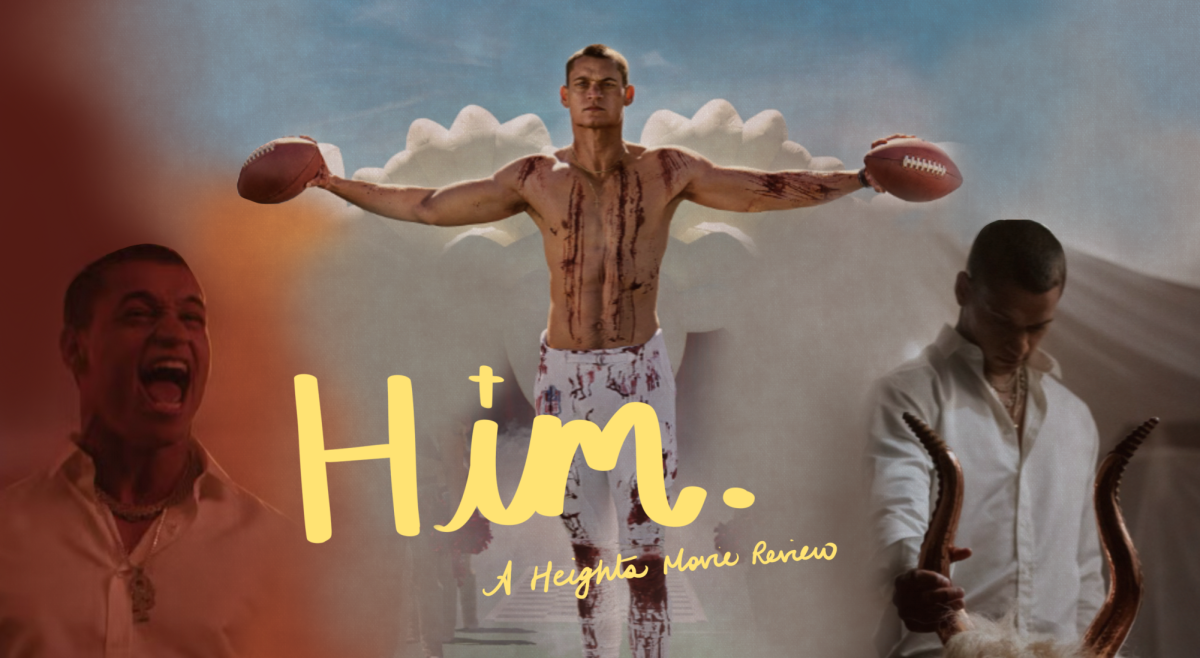

Guadagnino has big expectations to meet following his two 2024 hit films: the nail-biting, fast-paced drama, Challengers, and the surreal, thought-provoking romance, Queer.

In After the Hunt, Guadagnino strays from his usual romantic longing, sensual gestures, and lingering shots where dozens of feelings are conveyed with few words. This new film does not revolve around a romance, but opts for a pragmatic dissection of sexual politics and activist culture.

After the Hunt begs viewers to contemplate the difference between “good” and “right.” But in failing to truly pick a side or fully dissect the root cause of the film’s tension, Guadagnino’s experimentation with more overt social commentary misses the mark.

The film primarily revolves around three characters: philosophy professor Alma Imhoff (Julia Roberts), her colleague Hank Gibson (Andrew Garfield), and Imhoff’s student protegé Maggie Resnick (Ayo Edebiri). After a dinner party one night, Gibson walks Resnick home, and the next day, Resnick shows up at Imhoff’s house in emotional strife, accusing him of assaulting her.

The film explores Imhoff’s perspective and the double-edged sword of being a successful woman in academia. Imhoff is expected to uphold modern feminist values and find pleasure in setting an example for the young women who follow in her footsteps.

She struggles, however, to support Resnick emotionally in the case against Gibson. As Imhoff’s past is revealed, it becomes clear that she is burdened by a deep bitterness caused by a traumatic childhood and her laborious career climb.

The story becomes more complicated when Resnick is suggested to be a disingenuous character—she is revealed to have plagiarized a paper and hails from a well-off donor family. Additionally, her identities as a Black woman and a member of the LGBTQ+ community are used against her assertion of innocence and victimization.

Having developed an unhealthy attachment to her professor, Resnick becomes more agitated with Imhoff as she is pushed away and increasingly invalidated. In one of the most intense scenes in the movie, Resnick slaps Imhoff in the face. This act marks the start of her revenge against her professor and proves her shockingly vicious nature when provoked.

At this point, the film diverges from the question of Resnick’s innocence and focuses on whether Imhoff can survive the damage to her reputation that her protegé is set on inflicting.

The actual encounter between Gibson and Resnick is never shown, only recounted by those involved, enshrouding the film in mystery. It’s left up to viewers’ interpretations to decide who to believe, forcing them to confront their own biases.

The intense, extensive dialogue throughout the film drives the plot. The conversations are charged with blatant criticism of “woke” culture and self-victimization—a direct nod at Guadagnino’s reason for making the film.

So, does After the Hunt live up to its predecessors? The answer is complicated. The film clearly has something to say, and while the beginning is promising, the argument falls flat in the latter half.

It’s not abysmal by any means—the shots are still beautifully composed, a staple of any Guadagnino film, and the tension between characters is palpable and compelling. But the #MeToo-era argument quickly becomes convoluted and, ultimately, half-baked. In attempting to criticize every side, the film loses its stance.

It’s certainly no Call Me by Your Name, where Guadagnino establishes a tangible yet questionable relationship but allows the viewers to decide for themselves whether or not it should be deemed “problematic.”

Where Call Me by Your Name is subtle, After the Hunt is outspoken in its ideals—the issue is, it isn’t exactly sure what its ideals are.