On May 12, 2008, Perry-O Sliwa was driving through her hometown of Postville, Iowa, when she heard a helicopter droning not too far away from her. The morning was the event of a raid conducted by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) that utilized 900 federal agents and multiple helicopters, spending $5.2 million to arrest 389 workers employed at an Agriprocessors slaughterhouse. Many of these workers were child laborers from Guatemala who came to America looking to support their families. The U-Turn, directed by Luis Argueta, examines the lives of members of Postville’s Guatemalan community in the eight years after the raid took place, as many of the deported or detained individuals worked with forensic psychologists, attorneys, and neighbors to attain “U-Visas”—visas that are supplied to immigrants who are the victims of crimes in the United States.

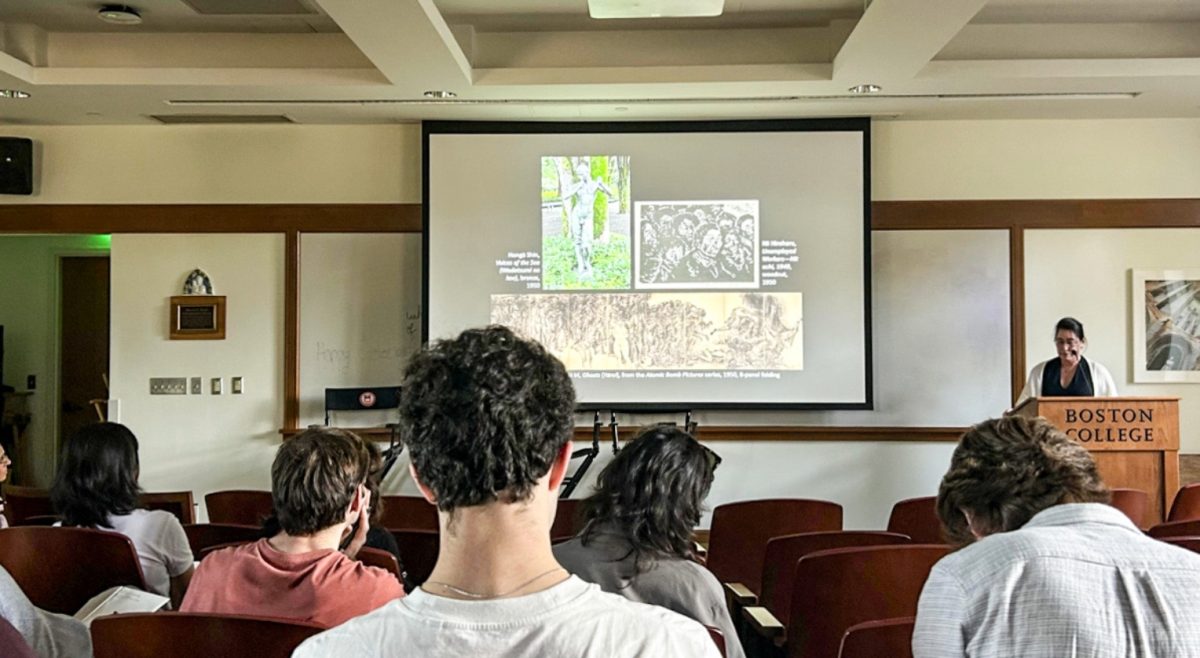

Argueta presented The U-Turn to an audience of 20 or so people last Monday evening in Fulton Hall, the second time he had screened a film at Boston College. Argueta told the audience how nine and a half years ago he had screened a trailer for the documentary he was looking to fundraise, abUSed. What began as a trailer morphed into a trilogy of films documenting the lives of Guatemalan immigrants travelling to America. The U-Turn is the last in this trilogy, and the only one in which Argueta interacts with the people he’s filming. Though he admits he attempted to remove himself from the film during editing, his presence is valuable both as a narrator and a subject. In this way the project mirrors the real-life experience of following friends and family over a long duration of time, dissolving the boundaries between the professional and personal.

The beginning of the film demonstrates how an investigation into child-labor violations at the Agriprocessors plant was put on hold to make way for a raid which ICE was planning, featuring Merlin, an immigrant whose dad worked at the plant. The film then cuts to 2016, eight years later, when Merlin is a teenager. This dichotomy gives the audience a breathtaking sweep of the time between the raid and the legal settlement which prosecutors hoped would amend some of the damages done to these families.

Merlin’s mother, Rosa Zama, told her story of having been shackled by the federal authorities with an ankle bracelet that prevented her from leaving her home. She was not allowed to work, rarely had food, and had to sell the car to pay for expenses. Sonia Parras Konrad, an immigration officer stationed in Iowa, worked with women like Zama who were employed at the Agriprocessors plant to help bring forward charges of abuse and sexual harassment alleged against their supervisors. Many of the witnesses were hesitant to speak out. It took the help of the local churches and community to build bridges between the workers and authorities. The film details the complex process by which Sonia brought in forensic psychologists from around the country to file a full report of abuses within a year’s period, before the statute of limitations was over. The final report included 60 psychological cases, 32 child labor victims, and 9,311 charges in total.

Some individuals, despite evidence and allegations of workplace misconduct, couldn’t qualify for U-Visas. Sonia attempted to grant them “Voluntary Departure,” which is when an undocumented worker leaves the country without a record of immigrating here illegally. Much of the film focused on the efforts of Sonia and Thomas Miller, the attorney for the child laborers who director Argueta brought back to America years later to testify against their abusers. Jimy Gomez is highlighted in this section of the film, as Argueta explores his hometown where he chopped corn for a living. Houses made of bamboo and unpaved streets reveal a world entirely alien to the one we live in. Though they lost the trial, Gomez speaks on how it was nonetheless a victory for him.

The U-Turn makes every aspect of its subject matter completely accessible to anyone without prior knowledge of immigration law. At the same time, the film conveys an intimacy that supersedes the formal jurisdictions of most documentaries concerning vulnerable persons—this complete transparency is without a doubt due to Argueta’s closeness to the community, and the impact he made on it. The camera does not isolate the subjects, but captures them at communion and backyard barbeques.

Argueta’s sense of beauty is apparent in the attention he gives to the natural landscapes of the towns he visits. Iowa is illustrated in long shots of highways and broad plains at sunset, while Guatemala appears to the Western viewer as liberated from the very modern conveniences people like Gomez risk their lives to realize. Argueta aims at reconciliation through a compassionate understanding of these topics, rather than through an exploitation of our sympathies, demonstrating that the lives he chronicles are worth more than rhetorical strategies for a political viewpoint. At the same time, one hopes that Argueta’s message will reach the ears of those who know little of the subject, or who refuse to listen to it, and impact an institution of human rights abuses that is more powerful today than ever.

Featured Image by José Vásquez