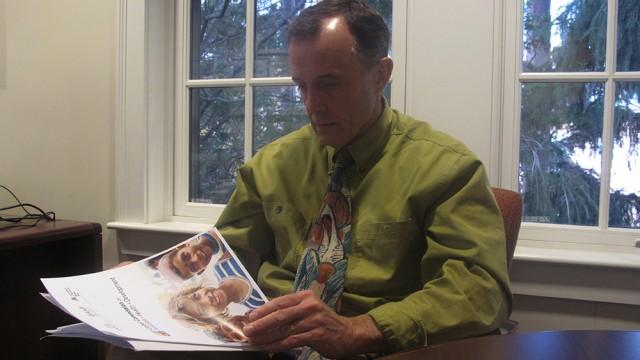

Thomas Chiles, Deluca professor of biology and vice provost of research and academic planning at Boston College, recently joined the Global Commission on Pollution, Health, and Development. The commission is an initiative of The Lancet, the Global Alliance on Health and Pollution, and Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine, with support from the United Nations Environment Program and the World Bank.

As vice provost of research and academic planning, Chiles oversees the entire research portfolio of the University. As a biology professor, he teaches a class called Molecules and Cells. His research focuses on infectious diseases, specifically immunology—how our bodies respond to attacks from pathogens, viruses, and bacteria. Chiles is particularly interested in infectious diseases that cause gastrointestinal distress.

“In the third world, enteric diseases account for the majority of morbidity and mortality in young children and infants,” Chiles said. His research is specifically focused on designing diagnostics using material science and engineering to improve diagnostic techniques in low- and medium-income countries.

“And I am, in part, at BC because that’s what we should be concerned with—with those who are least in a position to take care of themselves,” Chiles said.

The multi-nation commission comprises the world’s most influential leaders, researchers, and practitioners in the fields of pollution management, environmental health, and sustainable development. These experts are charged with writing a report that communicates the extraordinary health and economic costs of pollution globally and provides feasible solutions to policy-makers.

Chiles was asked to serve on the commission because of his expertise in water pollution, specifically water contamination by man-made pollutants such as bacteria and cholera, and his prior experience in the public health sector.

“This group of people has come together because pollution actually disproportionately affects poverty—the two are strongly linked,” he said. “Many countries are ill-equipped to deal with the problem and the people living in these countries don’t have the resources to protect themselves.”

The World Health Organization estimates that, in 2012, household air pollution caused 4.3 million deaths, ambient air pollution caused 3.7 million deaths, and unsafe water, poor sanitation, and inadequate hygiene caused 842,000 deaths. Contaminated soil at active and abandoned mines, smelters, industrial facilities, and hazardous waste sites have killed tens of thousands of people and injured hundreds of thousands more. By contrast, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria combined kill about 3 million people per year.

Chiles noted that developed countries increasingly export waste like asbestos to poorer countries, where the people working with the hazardous material are unaware of the negative impact it can have on their health.

One of the co-chairmen of the commission, Philip Landrigan, BC ’63, has spent his life fighting pollution as a public health care official, particularly pollution that disproportionately affects the poor, and Chiles said this is really what the commission is about.

“This is a problem I think everyone has a responsibility to recognize and deal with, so the commission is going to put together a report that really looks, for the first time, at the extent of pollution in terms of the global burden on health,” he said.

The commission is supposed to have a document ready to be delivered to The Lancet by December of next year. According to Chiles, commissioners were selected from various areas of expertise to ensure the report is credible.

“The commission needs individuals who are experts so that if some say, for example, ‘Here’s a solution for x country’s air pollution’ and it’s not feasible, an economist can provide a reason as to why,” he said. “We need to know this information–otherwise, the report will be immediately disregarded.”

In addition to the report, the commission will design a website that includes ways for compassionate people to get involved. Chiles said that one of the commission’s goals is to ensure that the report sparks a long-term debate on the issues.

“One of the things we’re envisioning is that the commission will have longevity,” he said. “We’re not going to provide a report and then say our work is done.”

Featured Image by Nicole Suozzo / Heights Staff