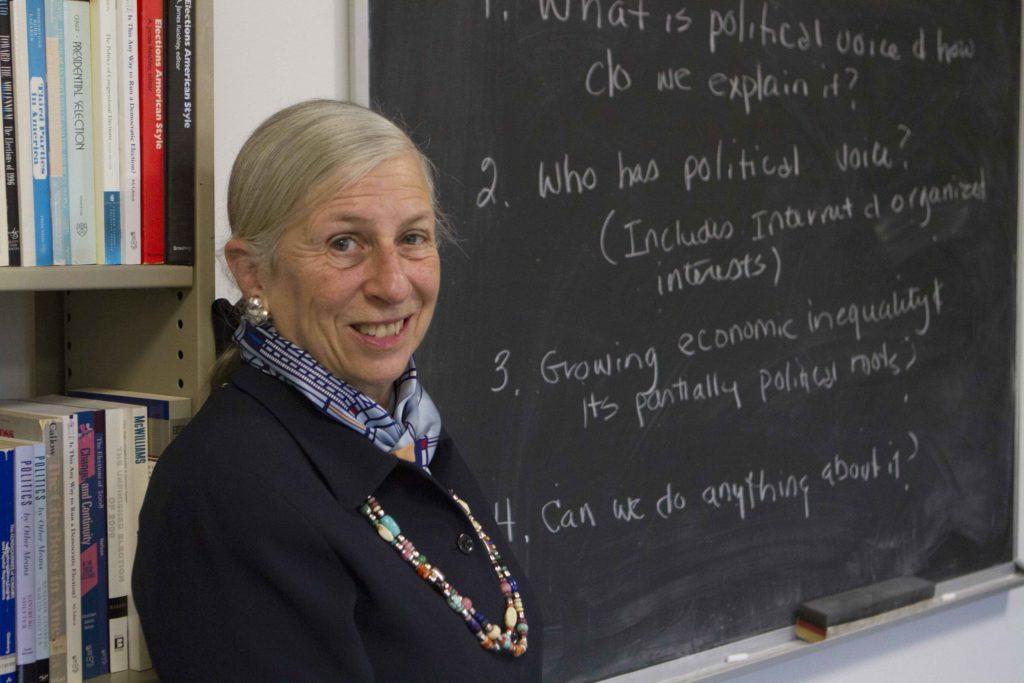

When Kay Schlozman, a professor in the political science department, arrived at Boston College to teach, tuition was $2,800. BC had just acquired Newton College of the Sacred Heart, a mile down the road. The “Hillside dormitories”—Ignacio and Rubenstein—had just been built the year before. All of its educational programs had reached coed status just four years earlier.

“I was starting on a journey and BC was starting on another journey, in a way,” Schlozman said.

When Schlozman entered the political science department in 1974, she was the only woman. In the greater University, she was one of seven—a mere 6 percent of professors at BC at the time. Schlozman said she was asked to be on seemingly every committee—she knew why, but the reason didn’t discourage her.

“I’m sure they put me on these committees because they needed a tenured woman faculty, but instead of acting like a woman, I acted like a political scientist,” Schlozman said.

She said that she showed that she had something to offer—not because she had some unique perspective as a woman, but because she was a capable scholar. Schlozman’s hard work, tenacity, and dedication didn’t go unnoticed. She quickly earned the respect of her peers, many of whom note that Schlozman is one of those few people that they can always depend on.

“People know that when you put her on a University committee, she’s going to do the work, know what she’s talking about, and be extremely fair,” said R. Shep Melnick, a professor in the political science department for more than 20 years. “The disadvantage of having that reputation is you get put on a lot of committees.”

Schlozman isn’t on nearly as many committees anymore. Now, 41 percent of professors at BC are women—but that’s not the only change that Schlozman has seen over the past 44 years.

“When I went to a women’s college, women couldn’t go to Yale, Princeton, Amherst,” she said. “It was a very different environment, so the choices for academically talented women were much more constricted. That’s different now.”

Despite the leaps that have been made for women in education over the past 50 years, not everything has been smooth sailing since Schlozman arrived at BC. Earlier in her career, she heard rumors of a male faculty member in her department harassing female undergraduate students.

“I got really upset, so what did I do?” she said. “I did the academic thing and went and read everything I could.”

Schlozman published an article in 1991 on sexual harassment on college campuses. She wrote about her findings on the statistics of sexual harassment between professors and students, as well as concerns of people in the academic world. She’s not sure that her colleague, now long out of the department, ever read it.

Schlozman said that going to Wellesley, an all-women institution, was the best thing she could have done at the time she was enrolled in school. Schlozman says she may have gotten lost in the crowd at a bigger, coed school, but at Wellesley she was given one-on-one attention that supported her academic success. When she was a junior, one of her professors took her to lunch, sat her down, and asked what she was doing about graduate school. Schlozman, who hadn’t really thought about it before, was taken aback.

“Especially then, but also possibly now… women students know they can do whatever they want, which we didn’t know in those days,” she said. “I think I needed that kind of boost to even know I could go to graduate school.”

Schlozman studied sociology and literature in college, but realized that she wanted to go a different way in her graduate program. She had always been drawn to questions and problems that had political implications, so after Wellesley she got her master’s and Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, and moved to Boston to teach political science at BC.

Schlozman is the brain behind the “Rights in Conflict” courses for sophomores—she saw that her second-year students were falling through the cracks, since their pick times didn’t give them a chance to get classes that made sense for their major. She developed the program—which focuses on areas like gun control, school desegregation and affirmative action, and freedom of speech and religion—not only to give sophomores a chance to take courses they were interested in, but to give Ph.D. students a chance to teach.

In order to supervise the graduate students in their teaching, Schlozman had to do quite a bit of research the first few years, because her own research has focused mostly on studying political participation, rather than rights in conflict. Schlozman said that she didn’t mind—she is really similar to an undergraduate in that she’s still curious to learn more about things she doesn’t know.

“That’s one of the great things about being a professor,” she said. “You get to learn new stuff all the time.”

Schlozman doesn’t shy away from exploring topics that don’t fit into her primary research interest of participation in American politics. She has started courses that are tangentially related, like the classes she taught on gender and politics. Her regular work doesn’t focus on gender, but she has written on the gender aspect of citizen participation. One of the great things about BC, Schlozman said, is that you don’t have to go through a ton of red tape to teach a course. If you have a good idea, you can make it happen.

“When I decided there was a demand and a niche for a course surrounding gender and politics, which I’d say was around 1978, I just did it,” she said.

Since then, the skeleton of the course hasn’t changed too much—the readings are different but it’s not night and day from what it was originally, Schlozman said. Although the course hasn’t changed, Schlozman has noticed some differences in the kinds of students that have walked through her door at BC over the years.

At the beginning of every semester, Schlozman asks her students to come in for 15 minutes and talk to her individually, so she can get a sense of who she has in her class. She said that recently, she’s seen a greater variety in regard to where students are from—BC now pulls students from all 50 states and more than 90 countries, while it used to be primarily for Boston-area commuter students. She says that she’s seen the caliber of BC’s students increase, and students are busier in their extracurricular involvements now than they were in the past.

“In that way, BC students have changed with the generations.”

When Schlozman had first arrived at BC, she wanted to get writing. Schlozman feared that if she didn’t get published immediately, she wouldn’t be able to get tenure. She ultimately became the first woman in the political science department to get it.

“I was like the world’s most naive professor,” Schlozman said with a laugh.

She went right to the office of Sidney Verba, her dissertation adviser from the University of Chicago who had recently accepted a position at Harvard. She asked him to write a book with her, and he obliged. Schlozman said that they found they could work together very well—they knew both how to fight, and how to get along.

“There was a point at which I moved from being a sort of intellectual follower to a leader,” she said. “To the last two books where I really took much more of the intellectual lead, as he began to wind down in a way.”

One of Verba’s former collaborators suggested that the three of them write a book on political participation and American politics. The trio quickly realized that they needed someone who could work well with statistics, so they turned to Henry Brady, a current Berkeley professor who at the time was Verba’s associate at Harvard.

Though the original collaborator, who suggested they write the book, dropped out of the project, Schlozman, Verba, and Brady began a group collaboration that would ultimately span over four decades, ending with their last book, Unequal and Unrepresented: Political Inequality and the People’s Voice in the New Gilded Age, that was published in May.

“I’ve had these really wonderful, really smart collaborators,” Schlozman said. “Everytime we finish something we say, ‘Well, It’s really been wonderful, it’s really been good,’ and then somebody else will say, ‘How about we….’”

“We’re sort of joined at the hip. We’re like family.”

This is one of Schlozman’s defining characteristics: She turns friends into family. Chuck Cohen, Schlozman’s childhood friend, said this is something she learned from her upbringing.

“She grew up in that kind of atmosphere and that kind of household,” he said of her seemingly genetic hospitality. “Not only her parents, but her grandparents realized friends are an important part of your life and are your family.”

Cohen said he originally became friends with Schlozman’s older brother Ken Lehman, but quickly got to know the entire family. He made toasts at Schlozman’s wedding and at her 50th wedding anniversary.

It seems that everyone who knows Schlozman knows her kids, Danny and Julia. Both got their bachelor’s degrees from Harvard before going on to graduate school. Julia is an attorney for the Northeast Justice Center, and Danny is a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University.

“As a family, they’ve been very much committed to issues of equality, and race and equity, which has been reflected in their philanthropy, as well as how they spend their time,” said Paul Lehman, Schlozman’s younger brother.

Schlozman often opens up her home—with a cozy living room that overlooks the Brookline Reservoir, and book-lined shelves—to students and faculty. She’ll have dinner parties, and she has a reputation for cooking for anyone who is sick, or in need of some assistance.

When Susan Shell, a professor in the political science department, arrived at BC, Schlozman made her feel at home immediately.

“When I came here as a beginning assistant professor and she was already here, she was extremely hospitable and invited me over for home-baked cake and tea, and we had a great chat,” Shell said. “So she’s been a great friend as well as a wonderful colleague to have over the years.”

When Shell fell ill years ago, while she had two young children, Schlozman rallied the political science department to cook for the family and get them through it. For Schlozman, work has never been an excuse to fall short for the people she cares about.

“She’ll always take care of the people she needs to take care of, but she’ll get her work done,” Cohen said.

Photo Courtesy of Kaitlin Meeks / Photo Editor