It’s a beautiful Saturday afternoon in the Mods. Some seniors are passed out on their couches, face down, after a long night at Tavern in the Square or Mary Ann’s. Some are at brunch, or braving the Reservoir to get in their run. A few more are starting the grill, salivating at their sliding glass doors to get outside and break into tailgating mode. Everyone is preparing for one thing: This afternoon, at 3:30 p.m., it’s gameday. Not just any gameday, though. It’s the one everyone had circled on their calendars since Orientation Weekend: Boston College football against the University of Notre Dame. Tailgating has just begun, parents arrive, and the entire class hopes that today, for the first time in a long time, it’ll be a great day to be an Eagle.

But TJ Hartnett, CSOM ’18, is nowhere to be found. He actually left hours ago to make sure today goes off without a hitch.

He’s thankful the game got moved back to 3:30, because if it was still a noon kickoff—like against Central Michigan or Wake Forest—he’d have to be up at 5:30 a.m., ready in Fenway Sports Management’s (FSM) Alumni Stadium offices. He’ll run to Dunkin’ Donuts first—a force of habit, because waiting for Corcoran Commons to open at 7:30 would make him far too late. He has to meet with an army of employees, most of them older and still learning the ropes—they all look to Hartnett, an undergraduate who has doing this for what seems like forever. He helps prepare all of the other employees who are working that day, with everyone’s schedules, and assigns people’s roles.

Hartnett meets with advertisers, who are rolling in quickly because their vehicles have to be out by the time the gates open. On his golf cart, he’s shuttling back and forth between the hospitality tents he has to set up on the tennis courts at the Flynn Recreation Center. He’s constantly on the phone with Newton Wellesley Hospital representatives, or Kayem Hot Dogs—today, the Celtics’ Jaylen Brown is one of these—to make sure they’re all ready to go. He’ll have to tag team to get Nissans and Chevrolets, the two car sponsors of BC, parked in strategic locations. As executives from the advertisers come through, Hartnett has to shmooze, making sure everyone is comfortable, and wanting to come back.

At 1:30, he has a second to breathe at Mod 20B. It’s not enough time to throw on the Superfan shirt and snap an Insta, because he needs to be connected to the radio in case something goes wrong. This day, it did—a GEICO trailer was in the wrong spot, so he had to make three calls to get it to where it needed to be. He’ll wave a bit to his family, half in green and half in maroon because his brother Patrick made the pilgrimage to the Midwest for his college days. But not too long, because the show can’t go on without him.

Timed perfectly with the advertising schedule, Hartnett arrives at Alumni at 3:15 p.m. to set up for the game. The first event of the game was Hartnett’s favorite: the Roche Bros. Supermarkets’ Ball Kid of the Game. He’s not directly responsible for this part, but he loves to hear the stories of these kids. A girl with cerebral palsy is selected at random. She receives a Doug Flutie jersey and walks onto the turf with her sisters, her first time on a football field.

“To see the appreciation from their parents, that’s why you work in sports, to meet these amazing people and hear their stories,” Hartnett said in an interview last week.

But there’s no time for that: it’s emcee mode. And, as Hartnett says, it was the most jam-packed game he had worked in the three years since he took the Alumni job. Immediately after the National Anthem, he grabs his mic and heads to the south end zone with his wireless cameraman shadowing him at every moment for Chevy’s Social Hub. He then races to Section R, Row 5, where the Delta Seat Upgrade fans sit. He can chat a little bit with them before, get to know their stories before the second timeout and they’re on the screen. Hartnett congratulates them for how lucky they are. Right when that’s over, he’s got to get back to the south end zone for the T-shirt toss. “Get out of your seats, here comes the throw,” he booms over the Alumni PA system. He tries his best to entertain, but not stand out so much as to make him the show—he’s only a small part of the action, and it needs to stay that way.

And that just gets him to the end of the first quarter, where the first big change of the game arrives. Because of an injury timeout, the Punt, Pass, Kick competition has to be moved to the fourth quarter. Jason Blanchette, the associate director of sports marketing, is in Hartnett’s ear, telling him they have to cut it. So instead, they go to StudentUniverse Toss—two students try to throw a football into a trash can in 15 seconds. Then comes another issue. As he runs out to the field, Hartnett’s earpiece separates. By the time he feels it go, he’s already on screen, talking to the crowd. Blanchette, who is supposed to be counting down those 15 seconds while Hartnett is constantly hyping up the crowd and speaking the whole time, can’t get in contact with him. So Hartnett has to count down the 15 seconds, without any clock while doing everything else he has to do at the same time. In the span of a minute, he has to remember an entire script, ad lib what’s happening in front of him, and remember a strict countdown clock that can’t be any longer or any shorter.

According to Blanchette, he was spot on. Then, Hartnett will do the Kayem Hot Dog Toss and the Dance Cam, before it’s smooth sailing through the second half. He’ll have to revert back to his marketing job, taking pictures of advertisements for verification. He can stand on the sidelines and be a “professional fan,” as he says, trying to pump up the crowd. This day, he’ll try to get a glimpse of his family standing in the crowd. But they’re only up when it’s still 14-13—not once Notre Dame pulls ahead in a 49-20 victory.

For Hartnett, it’s a constant balance of maintaining the business of sports and entertaining thousands of people, all at the same time, who are trapped into watching BC football. And it’s what every day should be like in the eyes of the Voice of the Eagles.

***

Hartnett’s energy and enthusiasm couldn’t have been possible without three ingredients: mascots, autographs, and impressions.

When Hartnett was 5 years old, he was terrified of people in costume. No more did this affect him than when he went to Camden Yards at Oriole Park. Once a summer, the family from Clark Township, N.J. would make the trip down to Baltimore to see the Orioles face their beloved New York Yankees. On this particular day, however, the Oriole Bird got a little too close to a young TJ. His uncle tried telling him not to be afraid, it was just a man in a costume. But he was inconsolable—that is, until he got a stuffed animal of it.

Since that encounter, Hartnett has loved dressing up. Unlike the typical answer for first career, Hartnett wanted to be a Disney character. He loved Goofy, because they were both tall, and Baloo from The Jungle Book, because he was—his words—“a boss.”

“I always wanted to be a character I thought it was the coolest thing to like—there’s just some sense of being like universally loved, too that I think anybody could strive for, and I think that was really attractive to me,” Hartnett said.

He ultimately went with Mickey Mouse most regularly, and much to his little sister, Annie’s, chagrin. At her second birthday party, Hartnett dressed up in a, frankly, terrifying costume of the famous cartoon rodent. It scared her, just like it had spooked him, even after he pulled off the mask and revealed who he was.

“I think you have to wait until you’re 8 to enjoy mascots if you’re one of my kids,” Jackie said, laughing.

Hartnett also loved the Disney characters because of his obsession with autographs. He collected hundreds of baseball cards to mail out for autographs. He penned individual letters to each athlete in a self-addressed envelope. Some of his best responses were among the world’s most famous athletes—his mom recalls Roger Federer and Brooks Robinson sending individual letters back to him. He’d run through the house whenever she’d let him know he got another in the mail, and hang them on his wall in his room. To this day, Hartnett believes the high number of athletes that wrote back to him fueled his love of sports.

While mascots helped him love entertainment, and autographs fueled his passion for sports, it was his impressions that put the two together. His brother Brian, three years his senior and a graduate of Notre Dame, recalls TJ mimicking the other people in town, neighbors, or fellow parishioners, as one of the first signs of his outgoing nature.

Hartnett took that talent into speech and debate, where, as a middle schooler, he began to compete. By the time he got to Union Catholic Regional High School, he was going up and down the East Coast in some of the area’s most notable tournaments. He mostly did declamation, a category in which competitors replicate the speeches of famous people. While Hartnett had his biggest success doing Conan O’Brien’s Harvard commencement speech—a piece that got him to nationals—his mother’s most memorable one is of him imitating Jim Valvano. The championship-winning North Carolina State head coach was given the ESPY’s inaugural Arthur Ashe Courage and Humanitarian Award for his battle with cancer. “Don’t give up … don’t ever give up,” Valvano famously said on that day. Jackie believes it says a lot about her son that, for all the speeches out there, he chose such an amazing man at such a powerful moment.

“He could see people following him, he just embodied a leader when he spoke,” Jackie said.

And for Hartnett’s part, he knew he wouldn’t want to take on the role of anyone else.

“I loved it because I loved the opportunity for people to walk out of that room and go, ‘Man, if I closed my eyes I would have thought that was Jim Valvano,’” Hartnett said.

***

“He loves to talk about it, all the time.”

Brian readily admits that TJ has him beat with his outgoing personality.

“He’s definitely the life of the party,” he said. But sometimes, that can border on a flair for the dramatic.

In his, as Hartnett says, “far-too-short” baseball career, Hartnett primarily played third base and pitched. But Union Catholic had a stellar third baseman coming in behind him. So, like how he moves from role-to-role now, Hartnett became UC’s Ben Zobrist, playing whichever position would get him on the field. In one of his final games of his career, he got his World Series moment.

Early in a game against UC’s biggest rival Jonathan Dayton High School, Hartnett booted a ball that led to three unearned runs. The team had a meeting at the mound, where Hartnett apologized and vowed to make up for his mistakes. Fortunately, he got his chance.

Still down by three with the bases loaded, Hartnett pulled a high, inside fastball down the left-field line, about 320 feet—the only place you could hit one at UC’s facility. He was the first player to hit a home run at the park.

“And I looked up as I crossed first base, I just remember the whole world go in slow motion,” Hartnett said of his biggest athletic triumph.

But his baseball coach and UC’s vice principal, Dr. Jim Reagan, had bigger plans for Hartnett’s career. When the team had batting practice, he’d notice how Harnett would call his teammates’ hits as they happened. In listening to his voice, Reagan realized that Hartnett would thrive as a broadcaster. Together, they set up a streaming service at UC where he did play-by-play for as many sporting events as possible. With a single camera that he’d connect to a microphone, Hartnett would pan the camera back and forth for volleyball and basketball games, speaking behind it and only making appearances when action was safely done. Sometimes, for basketball, he’d team up with a UC alum, whose son had been on the team and knew the school’s history in and out.

That single-man operation turned into one of UC’s biggest clubs, which is now sponsored by Under Armour, as well as a local bank. They have three different camera angles, one of which is always on the scoreboard. Graphics can come up on the bottom. And now, his little brother Patrick broadcasts the games, typically through Facebook Live.

“When I realized I wasn’t going to make it as an athlete, I wanted some way to stay in touch with the game, and be something that’s greater than just being a fan,” Hartnett said. “Having the opportunity to tell their real-life story, just beyond what people can see on the screen, that was an added incentive.”

***

Hartnett believes in that tired, and sometimes true, phrase: Everything happens for a reason. Because everything he did at BC came very close to never happening at all.

As a freshman, BC Athletics sent out an email searching for an emcee during men’s hockey and men’s basketball games. He had done some public address announcing before, but Hartnett knew he wanted to be involved in the athletic department in some fashion, and saw this as a great in for his two passions—marketing and broadcasting. Moreover, he wanted to be part of a team again.

But he misread the date when it was due—the flyer was different from the email, the former a week earlier. So he panicked and emailed Laurel Carter, a former BC Athletics employee, with his reel. She replied that he was totally fine because there were six more days.

“I think back to that moment, and I’m like, what if I never would have emailed?” Hartnett said. “Where would I be? It freaks me out, it really does. Maybe I’m never an emcee, and maybe I never get to where I am today.”

And also, he’d need to be in there for a callback. After one cold read, he got the job. A couple of months later, he turned that into a work study with the marketing department that eventually led to his job with FSM. His efforts also turned into an ad sales and marketing internship at NBC Universal, where he operated in a similar role as he does at BC.

His passion project, outside of emceeing, was to bring that same live stream to BC’s Olympic sports, based on what he had done at UC. BC’s associate athletics director for marketing and fan engagement, Jamie DiLoreto, trusted Hartnett, now his primary student liason, to do his thing.

“He made everything so natural, it was like having another full-time staff member of our department,” DiLoreto said. “He’s a true professional.”

With the help of a few friends and BCTV, Hartnett began running play-by-play streaming broadcasts of all of BC’s Olympic sports. He’d often one-man band it, producing, editing, shooting, and calling the games together. Though it likely would have happened eventually anyway, given how streaming services have evolved, DiLoreto says Hartnett’s efforts were crucial into ushering in BC’s ACC Digital Network Extra set-up that went into place this year.

“I’ve met very few students that I’ve seen and said ‘They’re gonna be famous one day,’ and he’s one of those kids,” said Katie Foley, BC’s associate director for sports marketing.

Hartnett’s proudest moment came after a men’s soccer game. The following day, Simon Enstrom, a forward, approached him, asking if he was the one on the call. Hartnett replied that he was, which prompted a thank you from Enstrom. His parents live in Sweden and, obviously, cannot get to any of the games. They had expected they’d never see Enstrom play in college unless he made it to a major tournament. But now, with Hartnett’s help, they can watch their son every day.

“That was the reason why I broadcast,” Hartnett said. “Bringing together families, being a team, and being an intermediary between the game and the fans at home.”

At the same time, he worked to build WZBC in conjunction with BC’s live streaming service, the club that ultimately convinced him to head to Chestnut Hill. When he came into it, the organization was exactly what he could’ve wanted—you get to call games all across the country, and be in the booth alongside professionals. In his first opportunity, he did play-by-play for men’s hockey against Harvard—an experience he said was unparalleled.

But he wanted the club to be something more. After all, it has produced successful alumni, such as ESPN play-by-play men Joe Tessitore and Jon Sciambi. There must be some measure of potential for members of the club.

So with Hartnett at the helm, WZBC drastically upgraded its social media presence, taking full stock of its Twitter account. He added work in tandem with BC’s streaming campaigns, and developed their own website for broadcasts and articles. In the process, WZBC has legitimized itself and brought in new blood from freshmen.

“We always want to build WZBC to leave it in a place where it’s better than when we came in,” Hartnett said. “And it’s two-fold—it’s completely different from when we came in as a freshman.”

His proudest moments as a broadcaster come in baseball, where WZBC is the team’s primary voice. Over the years, Hartnett has taken the lead as being the man behind the mic for Mike Gambino’s team. Throughout Birdball’s run to the Super Regionals, WZBC was there the whole way. And Hartnett was the man on the call as the Eagles gave it their all in Miami. It’s a source of consistency the Birdball head coach has come to greatly appreciate.

“There are 40- or 50-year-old guys who have been doing it forever, and TJ can stack up with any one of them,” Gambino said.

The only struggle he has is in balancing his objectivity and his fandom. While some may grow cynical with all of the highs and lows of covering the Eagles, Hartnett admits it. He’s a BC homer, albeit not Ken ‘The Hawk’ Harrelson level. But what he never is anything but truthful to what he puts out there.

“I’m not fake, in terms of what I put out there,” Hartnett said. “If you look on my Twitter, it’s me pumping a certain BC sporting event because I’m trying to get people to go. I’ll also say things honestly, but I’ll do it in a way, like, ‘If we do this next time, guarantee we win.’ But it’s a really tough line to toe.’”

As he reflected on all he’s done at BC, he wonders how much longer those days doing everything are going to last. He now arrives at every child’s most feared crossroads: between living the dream and living practically. And while he doesn’t know what the future holds, he understands that his most difficult, jam-packed day—when he’ll have to decide on being behind the mic or behind a desk—is yet to come.

“I wouldn’t have a problem being a fan again, and I’ve lost that—I’d like to get back again,” Hartnett said. “But it’s also tough to not give it a try again, to go to a small market, and maybe 10 years down the road, I’ll get my shot.”

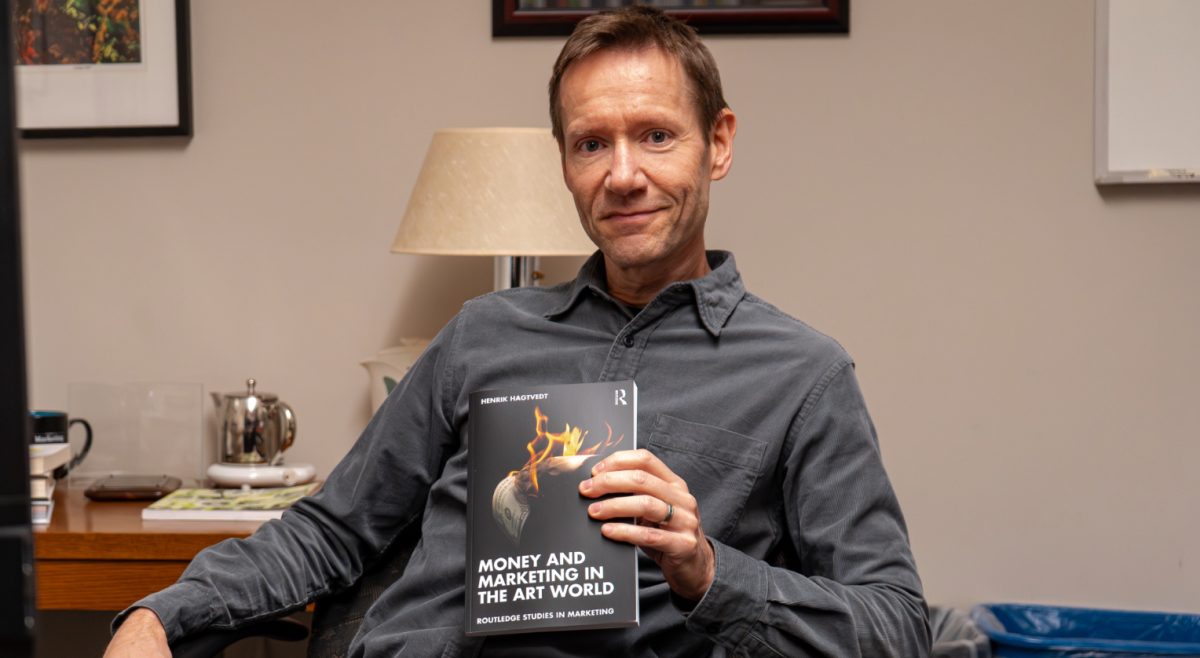

Featured Image Courtesy of TJ Hartnett