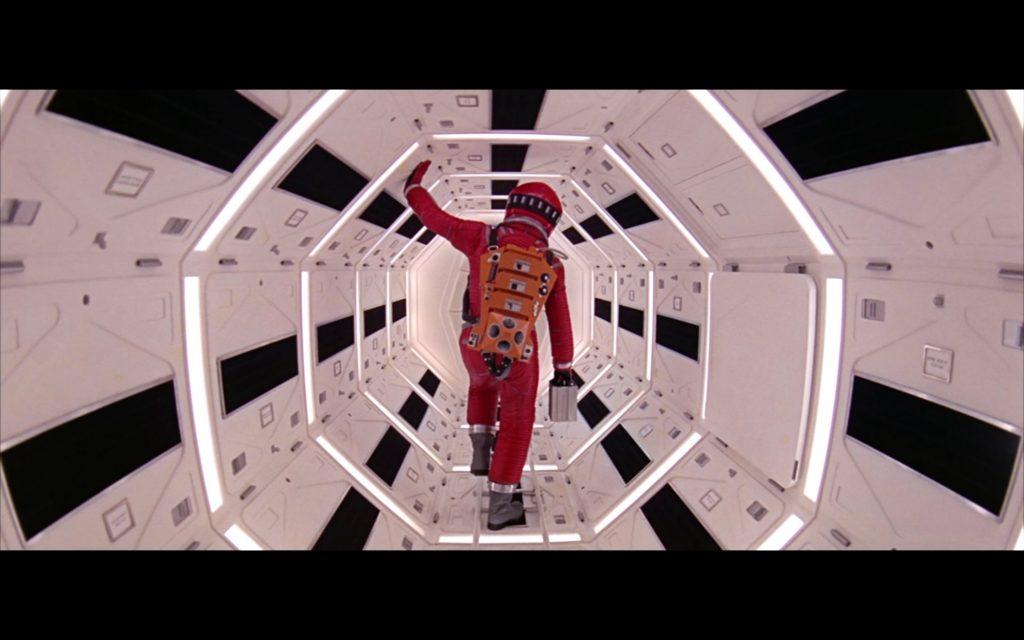

If you wander into a multiplex this summer, you may be lucky enough to happen upon a newly “unrestored” 70-millimeter print of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey screening in celebration of the film’s 50th anniversary. This new print from Warner Bros. isn’t remastered or re-edited—instead, this release intends to show the film in all its perplexing glory, projected on the big screen the way viewers would’ve had to have seen it in 1968. The film itself hasn’t been altered in the slightest (don’t expect any never-before-seen deleted scenes), since this print was struck directly from the original camera negative. By the light of the projector, Kubrick’s film springs to life, revealing images that will impress and provoke first-time viewers and those familiar with it all the same. The experience of watching (and hearing) this science fiction marvel on a giant screen is overwhelming, and it’s one that won’t soon be forgotten.

Nearly everything that could have been said or written about this film has been said or written, but for those unaware, Kubrick’s film is … admittedly hard to summarize. It opens with the “Dawn of Man” sequence, which captures the exploits of a group of apes living on the earth some millions of years ago. With the help of a nifty match cut, we soon jump to the year 2001, where we meet a group of scientists convening to address a strange artifact discovered on the moon, before finally joining a team of astronauts, Frank and Dave, aboard an expedition to Jupiter. Connecting these three storylines is the appearance of a pitch-black monolith, a strange slab of unknown origin that influences those near and around it in mysterious ways.

This past week, I was able to catch the “unrestored” print at an old New York cinema. Having seen it a number of times before, I knew 2001 to be a strange film, but this recent viewing helped me understand that the central clash of aesthetic and thematic styles—a mundane formalism and an erratic chaos—accounts for some of its mystique. If you somehow manage to watch only the first half of the film, you’ll notice that it’s far more interested in the mundanity of the future than most people tend to admit, as Kubrick fixates on the drawn-out process of spacecrafts landing, satellites orbiting the earth, and centripetal jogging. The film is clearly interested in spectacle and most of it still manages to astonish, but it’s difficult for me to gauge whether Kubrick was actually interested in future technology (or VFX technology), or if it’s simply a larger punchline about how technology sucks the emotion out of us. Either way, the scenes depicting process are filmed rather formalistically, emphasizing static, symmetrically framed compositions that work in juxtaposition to the furious bouts of emotion and feeling that come through in some of the film’s most memorable moments: Dave “killing” HAL, scientists discovering the monolith on the moon, and the apes learning to kill.

These moments of disruption see Kubrick break from his formalism, featuring instead shaky handheld camerawork, disturbing psychedelic imagery, and an ear-piercing sound (excerpts from Richard Strauss’s “Thus Spake Zarathustra”) that signify both a narrative and a filmic breakdown. These infrequent but potent moments of ecstasy are the ones that bridge the gap between us and these monotonous characters, because they remind us of the characters’ essential humanity, if only for a few brief minutes.

So much of 2001 is about control (or perceived control), and how technology and other tools offer us a feeling of assurance. Kubrick spends so much of the runtime immersing us in his strange, often prophetic vision of the future and its technology, establishing a necessary stillness before things inevitably go wrong. HAL’s mutiny results in a temporary loss of control that ends tragically for the humans, and the infrequent but haunting appearances of the monolith further remind the characters of the uncertainty of the cosmos—no technology or rationality can account for these mysteries. The film’s masterstroke is the way it slowly familiarizes us with its world of tomorrow, before dragging us out of the familiar and into the uncanny, ultimately suggesting that human progress can only occur when we deviate from the norm and embrace the unknown.

70mm screenings will begin on June 15 at the Coolidge Corner Theatre.

Featured Image by Warner Bros.