In the intimate confines of Boston College’s Bonn Studio Theater, Evgeny Ibragimov raised a walnut baton adorned with hazelnut sprigs, and the room fell silent. Known also as Shaoukh Ibragim, he stands as a living bridge between two worlds: the ancient traditions of the Circassian people and modern academic halls in New England.

His presence on campus this November marks more than a simple cultural exchange—it represents an act of preservation, resistance, and celebration.

Ibragimov embodies the role of the dzheguako—the traditional Circassian master of ceremonies, storyteller, and keeper of cultural memory. In his homeland of Karachay-Cherkessia, nestled in Russia’s North Caucasus region, such figures once stood above society itself, wielding the responsibility to speak truth to power through art and story.

Today, as a director, playwright, and puppeteer who can no longer work in Russia due to his opposition to Vladimir Putin’s regime, Ibragimov carries on this tradition.

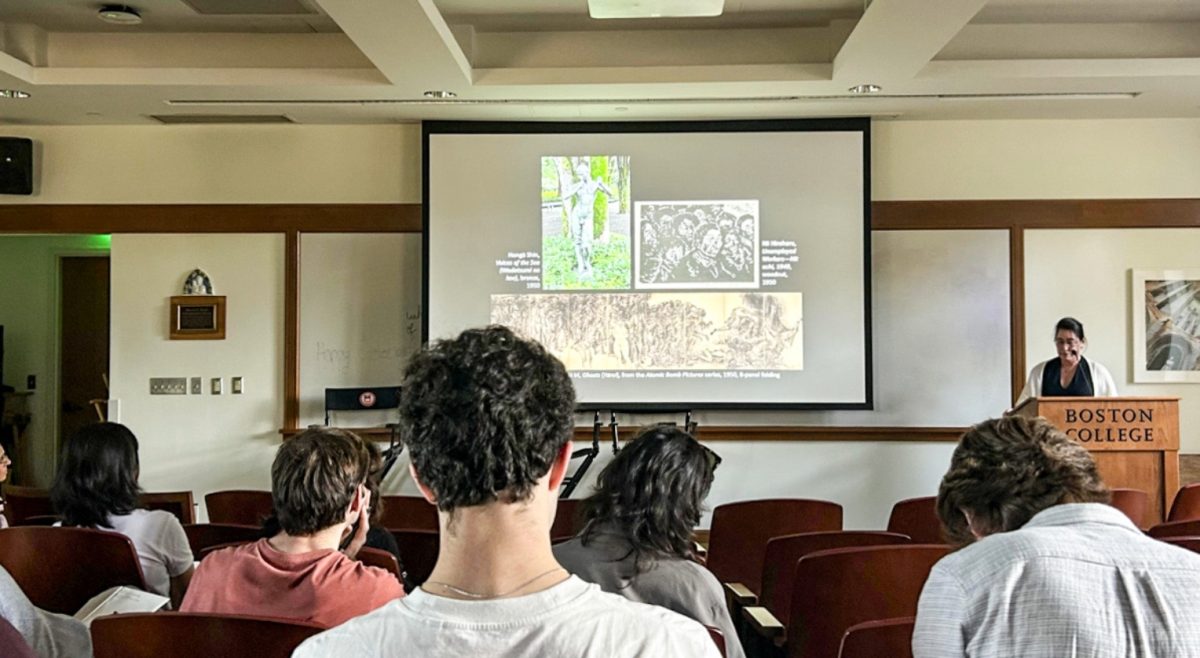

His weeklong residency at BC unfolded like a carefully orchestrated dzhegu—the traditional Circassian carnival that once marked every significant moment in community life. Through workshops, a presentation, spontaneous interactions on campus, and a culminating performance, he wove together the threads of a culture that has survived centuries of attempted erasure.

The story he told is both personal and universal. It’s of a people who, despite facing genocide and displacement under Russian expansion and powerful Ottoman influence, maintain their identity through art and memory.

Dressed in a cherkeska—the traditional knee-length jacket with its distinctive cartridge holders and warrior’s belt—Ibragimov moved through the space as both performer and teacher. His puppet show, “An Old Tale: The Legend of Happiness,” transformed the theater into a timeless space intertwining love, duty, nationalism, and fortune.

The performance began with the haunting notes of a traditional three-stringed instrument before unexpectedly flowing into Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” a musical metaphor for the cultural synthesis that marks the Circassian diaspora experience.

The history he shared is sobering. Before 1763, Circassia was free, its 12 tribes maintaining a unique nobility system untainted by bribery or purchased titles. Today, following centuries of conflict and a genocide acknowledged only by the country of Georgia, only 5–8 percent of Circassians remain in their ancestral homeland. The rest form a global diaspora, their culture preserved through stories, songs, and the kinds of performances Ibragimov brings to life.

Yet, there is joy in his preservation work. During the puppet show, love-struck puppets passed through the audience’s hands, creating an intimate connection between viewers and the old tale. Through the Russian to English translation by Polina Dubovikova, a Boston-based actress, singer, and translator, Ibragimov shared personal accounts of learning about the real history of his people one summer as a boy tending sheep in the mountains.

He detailed his fascination and love with puppetry and theater, and described himself as a lifelong learner. This personal touch transformed the historical trauma into a story of resilience and continuity.

The significance of his work crystallized in his mention of the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, where he said Putin’s deliberate omission of the Circassians from his opening ceremony speech spoke volumes about ongoing erasure. In response, Ibragimov’s art serves as a form of gentle but persistent resistance, keeping alive not just stories and traditions, but the very spirit of a people who refuse to disappear.

At the end of the weeklong residency, it was clear that Ibragimov did more than share his culture.He demonstrated how art can serve as a vessel for survival, a bridge between past and present, and a testament to the enduring power of cultural memory.

At BC, far from the Caucasus Mountains, he has proven that the dzheguako’s sacred task of preserving and transmitting culture remains as vital as ever.