One. Two. A pause. Three. A longer pause. Four! Start again.

Circle Mirror Transformation starts as it ends: with a theater game. Set in a summertime adult acting course, the play follows five residents of Shirley, Vt. as they learn arguably little about traditional theater, but a remarkable bit about themselves. Circle Mirror Transformation, presented by the Boston College Theatre Department, brought a living realist portrait to the Bonn Studio Theatre this weekend. It was a rare production that kept itself acutely concerned with character, avoiding traditional plot points and instead developing relationships through awkward and seemingly slight dialogue. Much of the plot kept entirely to the subtext-and many of the show’s most telling moments were silences.

The show begins in medias res, with the four students and their teacher, Marty (Alexandra Lewis, A&S ’14), lying on the wood floor of an acting studio, playing a counting game. Feeling out each other’s pauses, the five characters collectively try to count to 10, breaking silence with the next number in the sequence. Inevitably, the actors count over each other, and the exercise begins again.

GALLERY: Circle Mirror Transformation

At face, Circle Mirror Transformation is a narrative on failure-these characters are bound to fall short of what they set out to do, necessarily colliding along the way. Playwright Annie Baker, however, is eager to look beyond that. For her, it never especially matters what the characters are counting up to, or why they’re trying to get there-even the class itself never seems to fully understand the reasons for these games. Since there’s little motivation for the actors in the activities themselves, the focus is moved to the interaction in these seemingly trite classes. Circle Mirror Transformation is the story of the collisions along the way.

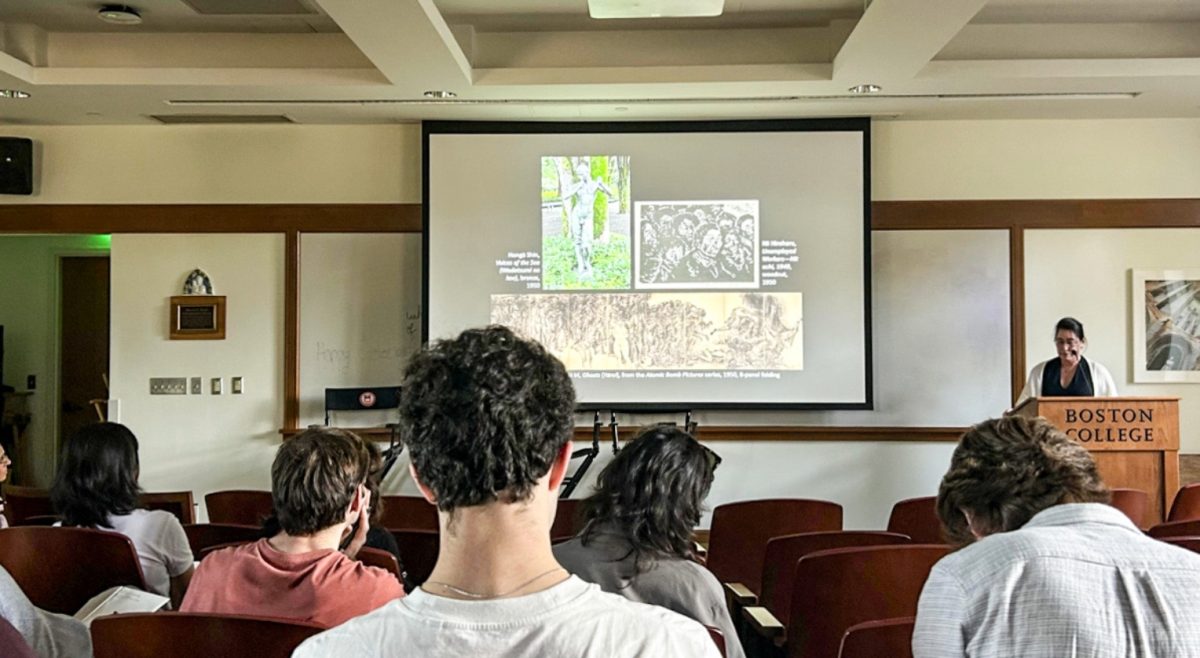

Director Maggie Kearnan, A&S ’14, paid particular attention to bringing out these small collisions hidden in the script. Audience members sat on three sides of the stage and were positioned remarkably close to the action. There was a lot less potential to trick the audience when it sat at such a broad angle. The actors moved very organically about the stage-the show wasn’t blocked with any strong sense of geometric order. Even foundational ideas of movement didn’t seem to apply in Kearnan’s production. Movement had less to do with plot motives and an awful lot to do with objects that incidentally fascinated, or had some simple functional purpose for the characters-an exercise ball, a mirror, an outlet to plug in an iPhone, a cubby for a backpack, a water bottle.

RELATED: Senior Maggie Kearnan Discusses Directorial Debut

Lauren (Julia James, A&S ’17) is the youngest member of Marty’s acting class, a high school girl taking the class with the hope of preparing herself for the role of Maria in her high school’s upcoming production of West Side Story. As the class goes on, Lauren grows increasingly skeptical of Marty’s acting games. Her role is particularly important to the play in that she carries many of the viewer’s doubts.

Lauren’s impatient, immature attitude toward the class mirrors the careless decision-making of the adults around her. In one theater game, each member of the class is instructed to write down a secret no one has ever heard. The secrets are then shuffled and read anonymously in the circle. While Lauren’s silly response manages to draw a disapproving look from Marty, it’s a secret presumably belonging to Marty’s husband James (Colin O’Neill, CSOM ’14) that proves to destroy a marriage.

Schultz (Ben Halter, A&S ’16) and Theresa (Sarah Devisio, LSOE ’14) strike up a romance in the class, only to have it complicated and then cast aside over the course of the summer. Schultz, perhaps the most visibly moved by Marty’s teaching, is a middle-aged carpenter, recently divorced but still wearing a wedding ring at the show’s start. Devisio and Halter have undeniable chemistry on stage, and much of the show’s plot is driven by Schultz’ unwavering hopefulness-and hopeless pursuit of Theresa.

Throughout the show, actors would incrementally drag open a curtain covering a giant mirror along the backside of the classroom. At first, the mirror seems to represent the growing self-awareness of the characters very neatly, but by the shows end, it becomes clear that these characters aren’t “developing” so much as colliding and falling apart again. The Circle Mirror Transformation suggests that the nature of people isn’t so open to change, but that circumstances are. It would take more than a summertime course to make Lauren a great actress, and more than a summer romance to heal the wounds of Schultz’ divorce.

In a cast of five, there’s no room for weak performances. Fortunately, the actors seemed to prop each other up. This was an unusual production in that no one took away or stole from the energy of it, a testament to Kearnan’s focus on the smallness of the show.

By the end of the show, the mirror at the back of the stage was reflecting more the audience than the actors themselves. Fittingly, the play ends as it starts: with a theater game, but this one transforms into a real-life encounter. Schultz and Lauren are first just playing themselves 10 years from the end of the class, but in time, it becomes clear they are themselves 10 years from the end of the class. It’s Baker’s reminder that theater, at its truest, is more than an abstraction of life-it is life, and it’s ever ready to start again.