Many historians have theorized on why the Cold War ended, but in his most recent book, Global Rules: America, Britain, and a Disordered World, James Cronin is concerned with a different question: the new world order that the United States, Britain, and more generally, the West, proposed at the time the Soviet Union fell.

Cronin, a professor in the history department, sought to understand this policy framework that came to prominence in the wake of the Cold War—an alternative world order that challenged and effectively undid the economic model practiced in the West prior to the Cold War.

Cronin considers the economic and political implications of this new world order for foreign policy, as well as the challenges presented to it since its establishment.

The book, published through Yale University Press, is the latest addition to Cronin’s collection of published work, which includes The World the Cold War Made, New Labour’s Pasts, and Industrial Conflict in Modern Britain, among other titles.

The economic crises of the 1970s made the established economic model—one that largely followed the theories of British economist John Maynard Keynes and favored government intervention—problematic, causing the West to reevaluate its approach to economy and to society, at large. These economic issues, paired with the close of the Cold War in 1989, paved the way for a new body of economic policy to come to prominence.

This novel social and economic approach that was adopted by the United States and Great Britain in the 1970s and the 1980s put greater emphasis on the market and market-based solutions, and less emphasis on the state, which was not the case 10 to 20 years before, Cronin said.

The book also considers how this new economic policy—often referred to as neoliberalism or market fundamentalism—was paired with a renewed social focus that favored human rights and democracy.

Cronin argues that this growing international consensus on the importance of human rights and democracy was borne out of a struggle for self-determination, and a struggle against Imperialist and Colonialist regimes, as many nations became newly independent by the end of the Cold War. Furthermore, Cronin notes a shift that began at the start of the 1980s, as US foreign policy began to support what would eventually emerge as a wave of democratic change in Latin America and the rest of the world, with a novel commitment to human rights.

“So what I’m arguing is that by 1989, when the Cold War really came to an end with the collapse of socialism in Eastern Europe, the United States had developed a policy—a policy framework—in which free markets, market-based democracy, and human rights were very prominent,” Cronin said. “That was, in a sense, the formula—the paradigm—that the United States pushed and many countries adopted and used as a guide to building a post-Cold War world.”

Ultimately, Global Rules makes a case for the dominance of this post-war policy framework, which arose of out the dynamic social, economic, and political climate of the 1970s and the 1980s.

The book also addresses its role and impact today, noting the challenges and crises this system has faced since its establishment. It takes the story beyond the early 1990s, when this new framework was being implemented, and examines how it fared in the 1990s and 2000s, Cronin said.

“The fact that this neoliberalism or market fundamentalism was a key guide to policy—it is the dominant ideology or principle behind much of economic policy both at home and abroad—makes it very consequential,” Cronin said. “It makes it really important. Whether it’s good or not, it’s the reality that one has to recognize and deal with.”

In writing this book, Cronin sought to understand a time period in American economic and foreign policy that most historians of American foreign policy ignored—the 1970s until the 2000s. For Cronin, the 1970s represented a large turning point in international relations, specifically in United States, British, and Western foreign policy.

“These momentous changes—a shift toward a neoliberal world order, a market-based world order, the shift toward a more democratic and human rights-based world order—those things had been largely missed by scholars, and therefore, in particular, the meaning of the ending of the Cold War had been only superficially grasped,” Cronin said. “So, I meant to repair that and to provide an account of something that was not only missing, but was hugely important for our current world.”

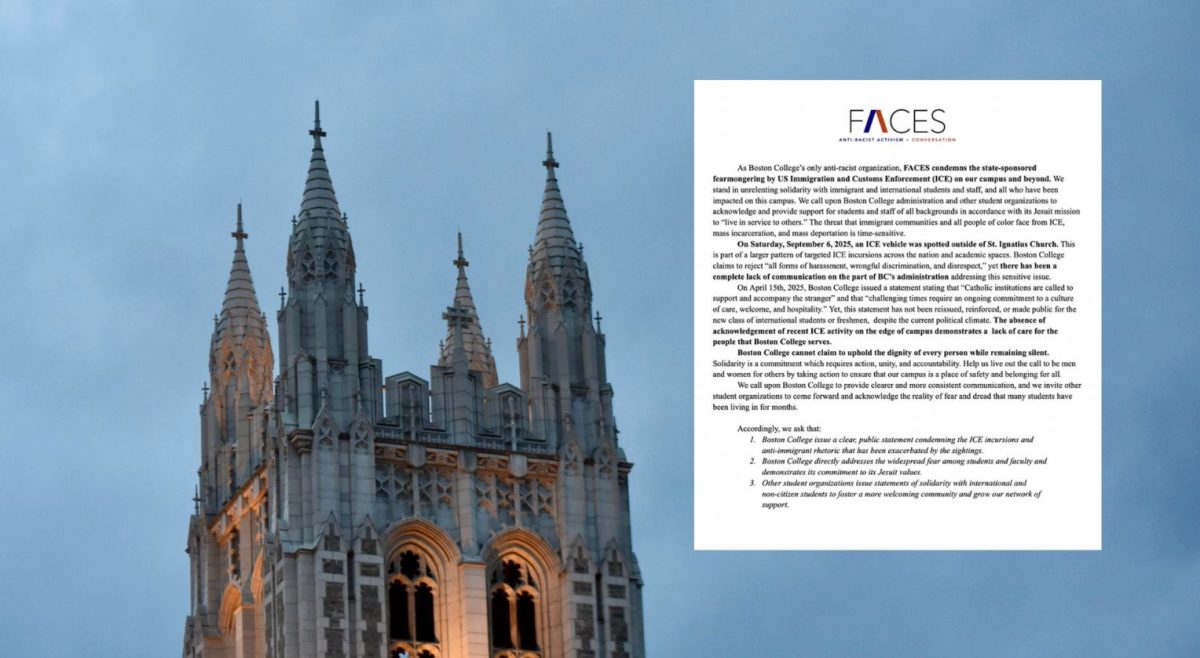

Featured Image by Margaux Eckert / Heights Staff