“That’s her,” said Holden Ford, FBI special agent, to Bill Tench as a yellow taxi pulled up.

Out steps the professor, Wendy Carr, to consult on Ford’s project and help with the classification of subjects in the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit. Her introduction comes after Ford states she “has something,” prompting the gruff Tench to comment on Carr’s beauty only to be refuted by Ford’s excitement at her interest in the project. Carr pointed out the admiration for, and prominence of various sociopaths in the world—pointing to the examples of Andy Warhol and Richard Nixon. Carr then states, “Thats why this work is so vital—it goes so much further than the FBI.”

Carr is the constant voice in Netflix’s series, Mindhunter, reminding the eager agents to remember science in all of their work with serial killers. Exciting and flashy, the show is partially based on one of the Connell School of Nursing’s own, Ann Wolbert Burgess.

“That’s her,” I thought, as soon as I walked into her office, Maloney 371.

I could tell that the woman sitting at the desk, absorbed in thought, was not the kind of person to mince words or waste time. Burgess had scheduled our interview for 2:40 p.m., not 2:30, not 3—something only people who know the true value of every minute of their time do.

Maybe all of her superstar would have been intimidating, if I wasn’t met by an immediate and welcoming invitation to come inside her office and make myself comfortable. She gave me a moment to get settled, and then, with a smile that gently reminded me that there is no time like the present, said, “Well, then, let’s get started.”

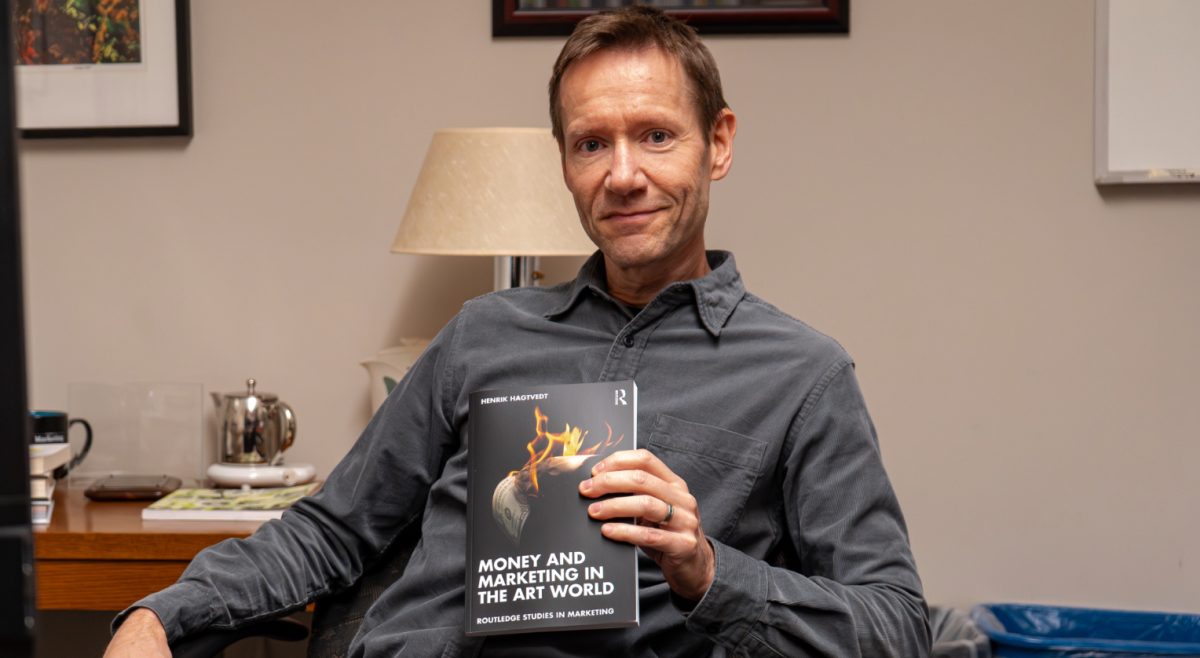

Burgess, who was a nurse, applied the conventions of her primarily female field to the male-dominated fields she found herself in. The woman sitting before me managed to forge a path, past inherent sexism, in the treatment of victims of trauma. She co-founded one of the first hospital crisis response programs, then worked with FBI Academy special agents to study serial killers. Called a “Living Legend” by the American Academy of Nursing, she has received various honors, including, but not limited to, the Sigma Theta Tau International Audrey Hepburn Award, the American Nurses’ Association Hildegard Peplau Award, and the Sigma Theta Tau International Episteme Laureate Award. Her most recent and popularly known honor is, of course, having a character based on her in Mindhunter.

In the blood-pumping series, working simultaneously in the man’s world and an arena of violence, Burgess’s character, Wendy Carr, works for the FBI in helping connect sex crimes to serial killers—universalizing databases and leading to connection of all the data for prevention of further offenses.

Burgess herself has spent the majority of her career as a forensic nurse. Her profession comes as no surprise, as she hails from an accomplished family of doctors and nurses.

“My uncle was in a kind of rural area in Maryland, and I’d go out with him, out to the houses, and he’d deliver babies … The next week there’d be a basket of apples or potatoes on the back porch—that’s how he got paid,” she said.

Burgess’s homegrown and unconventional initial exposure to medicine inspired her to go on to earn her bachelor’s degree from Boston University, her master’s degree from the University of Maryland, and her doctorate of nursing sciences, also from BU.

When Burgess began teaching at Boston College in the 1980s, she initially did not have any knowledge of research focused on rape, as few academics had published research on sexual violence. She was approached by sociology professor Lynda Holmstrom to start a new kind of research in order to help female rape victims. As a nurse, Burgess had access to hospitals and could act as a trustworthy figure for said victims—this would become essential to her and Holmstrom’s research, as Holmstrom could then interview the patients Burgess found and collect honest data.

Finding and speaking with victims during this time was an incredibly daunting task—“not that it’s any easier now,” she quickly acknowledged—and it was only through the careful interviewing of selected victims that Burgess and Holmstrom’s studies resulted in such success.

Her work aided the development of the universal method of diagnosing and assessing victims of rape. Now, police and doctors are more accurately able to determine the severity of a victim’s trauma and prescribe the most effective response.

“We put trauma on the map,” she said.

After her initial research into the diagnosis of victims, Burgess took what she had learned and began to look at the perpetrators of these horrendous crimes.

“This is, of course, is where the FBI came in,” she said in anticipation of the inevitable question about the methodologies she developed that became the inspiration for Netflix’s newest original series Mindhunter.

Burgess speaks about her research and accomplishments in such a way that makes them understandable for anyone not well-versed in forensic victimology, but not so simplified that you miss the complexity and importance of the work. She started by explaining the lack of sophistication of forensics at the time—she did, after all, begin her work in a time before the use of DNA as evidence, when police relied on blood type in order to catch offenders, which is far too broad to be at all reliable.

It was from this frustration that she and her FBI team—special agents Bob Ressler and Holden Ford—started to work backwards from crime scenes in order to identify the personality traits of offenders, such as the tendency of serial killers and rapists to “hunt” in the same area or for the same type of woman, as opposed to physical ones, such as blood type.

“All you have at a crime scene is the body,” she explained, and though that seems like an obvious statement, acknowledgment and leverage of the body and crime scene as a psychological resource for solving crimes was the first major step that needed to be taken in order for her work at the FBI to occur at all.

Of course, it was this interest in catching these serial offenders that led to Burgess, Ressler, and Ford conducting the interviews and studying the cases that inspired Mindhunter and their development of cutting-edge methods for crime scene analyzation. When asked about the accuracy of the show, Burgess is quick to state that it is the portrayal of the cases that is most accurate on the show, as opposed to her own personal stories.

She gives the specific example of the Jerry Brudos case—Brudos brutally murdered several women and fetishized red high-heel shoes. She described how the introduction of a high-heeled shoe to Brudos’s subject interview on the show was fictitious but based on a different case where Ressler brought detective magazine covers into an interview with a subject who had an obsession with them in order to get the subject to talk about why he committed his heinous crimes, which was highly successful. Burgess, Ressler, and Ford were in perpetual pursuit of the “whys” behind serial killings, and their work helped law enforcement begin to understand the seemingly unknowable motivations of America’s most dangerous criminals.

Though the research featured on the show was highly accurate, Burgess said that a lot of the personal information and interactions featured on the show were not. One of the big issues for Burgess was that the show portrays her as a psychologist instead of a forensic nurse. “I got that corrected as quickly as I could,” she said. It is easy to understand her frustration.

In addition to being miscredited in the context of her career, Burgess addressed the glaringly obvious plot line of overt sexism by FBI agents toward the character that she inspired on the show, and gave a surprising answer when asked, “What was your experience in the boys’ club that was the FBI?”

“Honestly, I really thought about this, and it didn’t matter [that I’m a woman],” she passionately attested. She acknowledged that it was “95 percent men” during her time at Quantico and that most women were in more administrative roles as opposed to being agents, but insists that everyone was still treated as an equal in the workplace. She spoke with great fondness of her time with the FBI. All of the research was on the workers’ own time, and out of pocket, so she and her fellow researchers truly bonded and worked as equals—she even goes so far as to call them her “brothers.”

Her daughter and partner on a handful of FBI cases, administrative assistant for the Gabelli Presidential Scholars Program Sarah Gregorian, confirmed how much of a family affair it was for Burgess to work on cases with her partners. Burgess’s partners often came and worked at her house on projects, and Gregorian got even more involved in her mother’s work when she interned with her at the FBI offices in Quantico, Va.

Burgess moved on from her work at the FBI and dove even further into the depths of forensic nursing, which has garnered her international recognition and acclaim. She has been asked to do talks and has completed interviews about feminism and being a prominent professional as a woman in countries including Iceland and Greece, and has also been asked to discuss her research in a talk at the Department of Justice.

It’s really no surprise that the writers and directors of Mindhunter used Burgess as a source of inspiration for the show—she has worked for decades on some of the most taboo and controversial topics in our society, and she has acted as a voice for the victims of sexual assault and rape that were unable to speak up for themselves. She worked collaboratively both here at BC and at the FBI in order to achieve her goals, and she is still working hard every day for her causes.

Burgess is relentlessly inquisitive, passionate, and humble—never boasting or seeming to care that her work is winning her awards as long as it is useful. When asked if there was one thing about her mother that she would want to share with the world, Gregorian answered, “She never sits down, and never lets anything stand in her way.”

Featured Image by Sam Zhai / Heights Staff